by David Kopplin

Abstract

The music of composer Henryk Górecki is enigmatic. Indeed, from his extreme modernist early works to the widely-popular Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, Górecki’s music never fails to illicit strong responses from listeners and critics alike. Using Górecki ‘s two string quartets as examples for analysis, this presentation focuses on a single, essential element in his music: namely, his manipulation of the experience of time. [David Kopplin]

Article

I.

In discussions of contemporary music, the experience of time passing is not an issue that has received much scholarly attention, in comparison to discussion of measurement of time. We measure how long a piece is, for example. We study metric modulation, or vertical pitch structure, but not time. Some believe, however, that music is essentially an emotional experience, related through time. Indeed, humans universally seem to rely on music to communicate emotions and states of being when words fail us.

In the music of Henryk Górecki, I have been struck by the way in which I experienced time when listening to his work. It is an emotional experience, created, I believe, by the way time passes in his compositions. His music brings the element of time strongly into the foreground as an expressive force. Górecki’s music steeps us in experiences of time passing. Listening to his music is sometimes like watching life in real time rather than in conveniently edited sound bites. My goal here, with Górecki’s first two string quartets as sources, is to discuss the concept of time in his music and to identify some issues that arise from his music, particularly an issue that is a central question at this conference—namely: what is this Górecki phenomenon?

I submit that Górecki’s music, especially these quartets, is continually portraying experiences of time that contrast the holy with the mundane, the everyday with the eternal, or as our host Maja Trochimczyk has written, the sacred with the profane. In listening to Górecki’s works, one is struck by music which alternates between extremes of time experience, varying from unrelenting activity yielding to moments that seem suspended in air, moments that communicate the experience of life at its rawest, most tedious, and most mundane, and moments that attempt to communicate an experience beyond time. Time passing is part of the listening experience in his music, and I believe that this taps into universal feelings that we all share. We know what waiting feels like, for example, we know about expectation and hope; some of us have known despair. Górecki is able to connect with our innermost humanity through the experience of time he creates in his music.

I chose to concentrate on the quartets because they are two significant, relatively recent, and purely instrumental works. Using a purely instrumental work was also important to me, because I could concentrate on how Górecki created emotional experiences without the aid of the human voice.

Theorist Jonathan Kramer, who focuses on issues of time in music, has aptly referred to our Western musical tradition as linear. In discussions of music, we continue to use Schenker’s terminology, talking of the Urlinie or “essential line,” or as Nadia Boulanger has described it, the “long” lines of a composition. According to Kramer, this linearity in music is a progression from moment to moment with an expectation that certain moments lead to other moments. In our Western tradition, tonality is a linear process, creating expectations of events, and goals, of which listener and composer are both equally aware. Leonard Meyer has said that an analysis of expectation is a prerequisite for understanding how musical meaning arises. Indeed, even novices understand this. When I ask my beginning music students to sing “do re mi fa sol la ti,” most of the class inevitably sings the final “do.” This is a linear process that most of us are familiar with. But what happens when the paradigm of expectation and goal is not invoked?

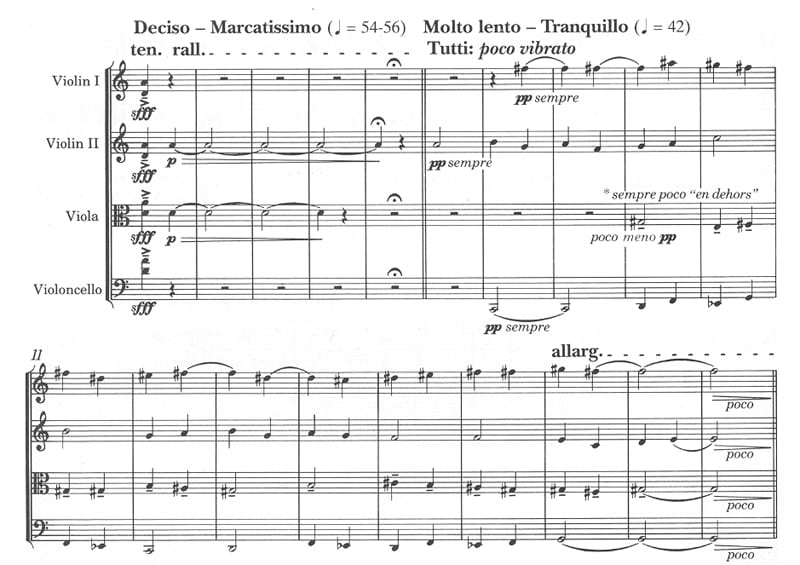

If we start from the premise that the music in Górecki’s string quartets is primarily non-linear, what then accounts for musical meaning that we find here? Starting even with the translation of the title of String Quartet No. 1, “Already it is Dusk,” it has been suggested by Adrian Thomas that, in Polish, the title infers transience rather than a sense of completion or goal, a better translation being “Already Dusk is Falling.” The original Polish suggests a less linear experience— of which we are a part, in the present moment. The English translation, on the other hand, suggests an experience that has finished or reached its goal. Let’s listen to this excerpt from Henryk Górecki’s String Quartet No. 1, the opening moments:

In this passage, there isn’t an obvious goal; we don’t have an immediate sense of where this music is going or what to expect next. It has a suspended quality, rather like being in limbo. Does this portray an experience of contact with the sacred? What can we notice about how Górecki creates an experience of time in his composing? The opening passage of the String Quartet No.1 that we just heard uses a 16th-century melody (which actually is the tenor line in a Renaissance-era Polish motet). This melody is combined with transpositions of its inversion, its retrograde, rhythmically displaced, all woven together in a dense contrapuntal structure. The voices enter in an overlapping fashion so that beginnings and endings are not heard. Entrances, rather than emphasized, are downplayed. This is a non-linear technique that I contend evokes in us a sense of timelessness. Another more textural contribution to the sense of timelessness is the lack of vibrato in the instruments. This creates a sound farther away from the human voice and adds an other-worldly dimension to our experience of this music. Adding to this quality is the way in which the old and new are brought together in Górecki’s works. The ancient and modern are commingled, and we as listeners are both disoriented and yet oddly at home. I believe this further contributes to our experience of timelessness.

Here is another example from his second string quartet—a musical quote from a traditional song you might recognize.

We have heard this music before, but we have never heard it before. Disorienting, yet familiar. This relates to religious experience in that an ordinary experience becomes transfigured or transformed – we know it, yet we know it not.

II.

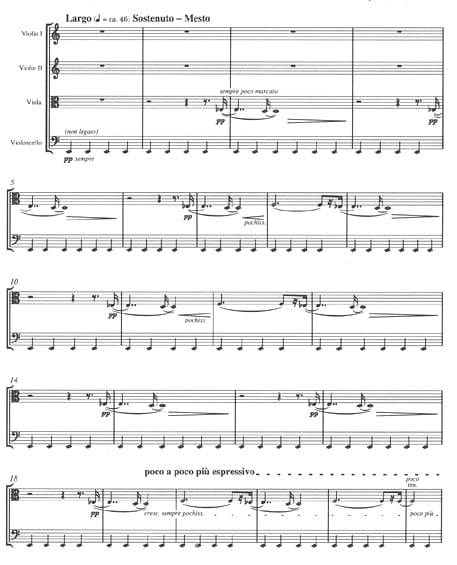

Now let’s look at the other side of the coin, everyday, ordinary time. The rhythm of life, what Trochimczyk called profane time. In Poland and other Eastern European countries under Communism, ordinary time is remembered as a time of intense waiting: waiting in lines for bread, waiting for years for the opportunity to own a car, waiting half a lifetime just to have a larger apartment. For many, it was also a time of waiting in fear. This is the beginning of the String Quartet No. 2:

The viola spins out a hypnotic moment – a three-note motive that never traditionally resolves, alternating between major and minor 7ths, jumping up to a minor 9th, always avoiding the octave. What would normally be an interval of motion, the minor 7th, is here an interval of stasis. This motive is tethered to the constant ostinato on E in the cello. Górecki thus evokes a feeling in the listener that is almost like marching in place, or waiting in line. Górecki also evokes in us the experience of time through frenzied, physical music. Listen to the passage that begins the 4th movement of the Second Quartet:

This is an earthly experience of time—music of the physical world. This music is rhythmically active and we are firmly aware of the insistent pulse of life; once again, it is a non-linear experience of time in that the sense of time passing is obliterated. Górecki, by capturing the essence of driving folk rhythm and repetition, has once again brought the old together with the new. These lengthy sections of music relate an experience of back-breaking work or furious dance, in which one loses track of time in the physical moment; thus rendering life more bearable.

III.

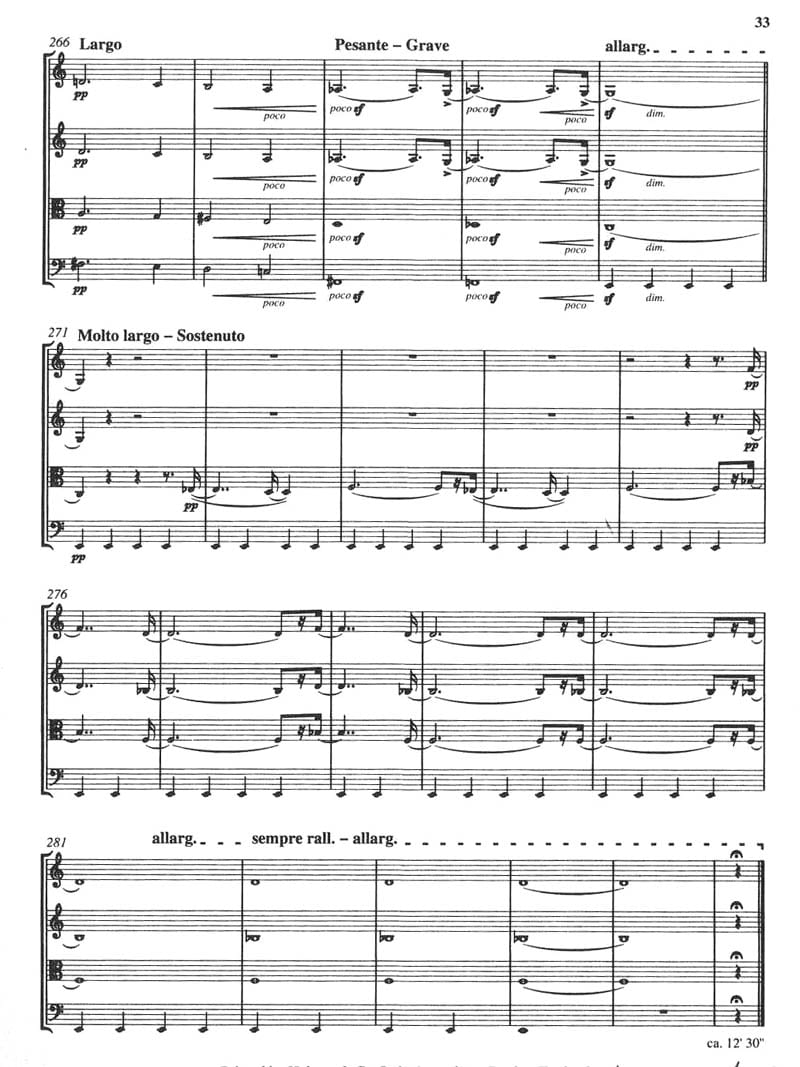

Finally, we come to a singular emotional experience of time in his music, which we have not encountered before in the string quartets. Listen now to the end of the first string quartet:

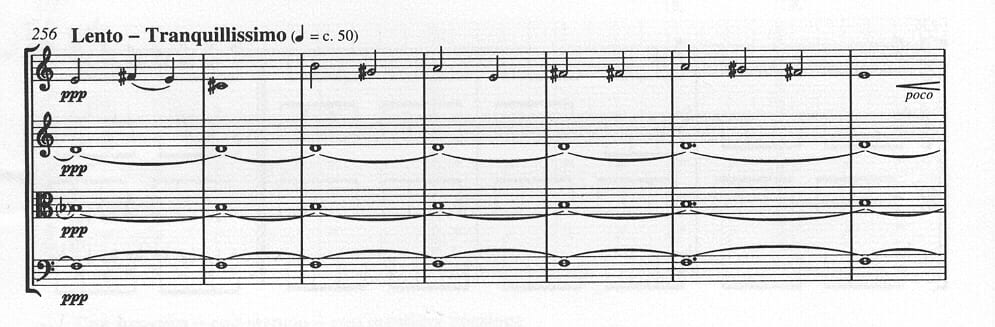

The ending of the first Quartet is a kind of resolution, though not in a formal tonal sense. In this passage, one attains the sacred through having experienced the profane. The listener’s experience of time in the preceding 14 minutes, one might say, is rewarded in the few triadic harmonies at the end. This timeless place, however, is not a limbo, but is a place of meaning and understanding to our linear ears. We are not twisting in the wind nor waiting in line — we are there, home, heaven, for a few tonal moments. Notice though, that a complete resolution in the traditional sense still was not possible. The moment passes as the A natural, the leading tone, returns to destabilize the B-flat major chord.

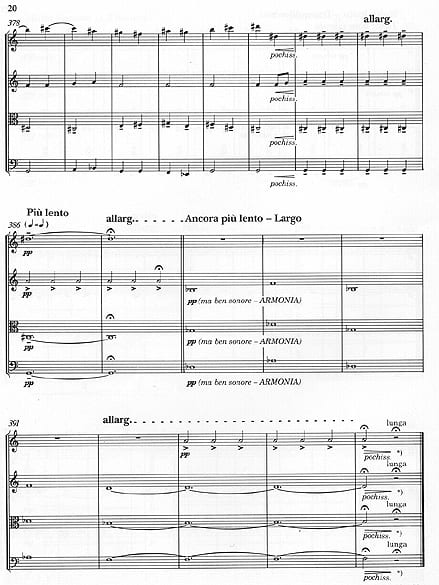

This passage, to me, is a musical representation of Faith, of Hope, that is absent from much of the music we hear in the West. Górecki’s sparing use of the linear, truly tonal, makes us feel as if there is someone or something that is there for us. These few moments at the end of String Quartet No. 1 sound like a tonal Benediction, full of compassion. This, to me, is part of the essence of Górecki’s success in the West; he is able to portray an experience, through the passage of time, which many listeners feel to be transcendental. Here is the end of the second quartet:

Through experiences of non-linear time—through waiting, the commingling of ancient and modern, the holy and the profound contrasted with the earthly and everyday, I believe that we are presented with an experience of the relationship between the sacred and the profane in Górecki’s music. And he does this by using time as his musical tool. We have heard several examples of how the non-linear can create musical meaning. Certainly, Górecki was in search of meaning. Speaking of the difficulties he has endured in his own life, Górecki was quoted in Bernard Jacobsen’s A Polish Renaissance: “The only way to confront the horror [of my life]. . . was through music. Somehow, I had to take a stand. The war, the rotten times under Communism, what madness! This sorrow, it burns inside me.” This discussion of time in Górecki’s music leaves many open issues – among them are tempos, his use of silence, abrupt shifts in meter . . . A discussion of those issues is for another place . . . and another time.

References

- Crosby, Alfred. The Measure of Reality: Quantification and Western Society, 1250-1600. Cambridge [England], New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Fink, Robert Wallace. PhD. Dissertation: “Long-Range Linear Structure and the Transformation of Musical Energy,” 1994.

- Harley, James. “The Górecki Phenomenon: Beyond the Marketing to the Music.”Sonances (November 1996).

- Harley, Maria Anna [now Maja Trochimczyk]. “‘To be God with God:’ Catholic Composers and the Mystical Experience.” Contemporary Music Review 12, part 2; “Contemporary Music and Religion,” ed. Ivan Moody, (1995): 125-145.

- Harley, Maria Anna [now Maja Trochimczyk]. “Górecki and the Paradigm of the Maternal.” Musical Quarterly 82, no. 1 (Summer 1998): 82-130.

- Jacobson, Bernard. A Polish Renaissance. London: Phaidon, 1996.

- Kerman, Joseph. Contemplating Music. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1985

- Kramer, Jonathan D. The Time of Music: New Meanings, New Temporalities, New Listening Strategies. New York: Schirmer Books, 1988.

- Meyer, Leonard. Emotion and Meaning in Music. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961.

- Saint Augustine. The Confession of St. Augustine. [Translated and selected by Caroline White.] Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans, 2001.

- Thomas, Adrian. Górecki. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Kopplin’s professional career in music began as extra percussionist for the Colorado Springs Symphony, and later as percussionist for the Colorado Springs Symphony Jazz Quartet. He has performed and recorded with San Francisco’s Clubfoot Orchestra, the Brazilian jazz group Araça Azul, and the Leisure Time Orchestra, among many others. In 1983, Kopplin was chosen as a Colorado Council on the Arts Fellow, and in 1984 and again in 1985 was chosen for the National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Study Fellowship. Kopplin holds a Master’s in Music from the University of Southern California where he studied composition with Bob Linn, Morten Lauridsen, Donald Crockett, and jazz composition with Vince Mendoza. He received the Ph.D. in composition at UCLA, where he studied composition with Roger Bourland, Daniel Lentz, Manuel Enriquez, and Ian Krouse, and musicology and ethnomusicology with Robert Walser and Susan McClary. Professional credits as a composer include film scores, incidental music for theater, works for chorus, chamber orchestra, full orchestra, various electro-acoustic works for chamber ensembles, songs, and works for jazz and Latin-jazz ensembles.

Kopplin is active as a writer and speaker. He has lectured on music for the Hollywood Bowl, Los Angeles Philharmonic and Pacific Symphony Orchestra, as well as guest lectured at the University of Arizona, Loyola Marymount University, USC, UCLA, Pasadena City College, El Camino College, Whittier College, the University of Calif.-Riverside, and Occidental College. He is currently Vice President of the College Music Society’s Pacific Southern Chapter. Kopplin presently is Assistant Professor of Music in music at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. He regularly contributes articles to Performing Arts magazine, program notes and features for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Los Angeles Opera, UCLA, the Phillip’s Performing Arts Center, and for the Hollywood Bowl, and served as editor of the summer Hollywood Bowl program guide from 1998-2001. The Górecki paper is a preliminary study towards his D.M.A. thesis on the concept of time in Górecki’s music.