Essay by Maja Trochimczyk

History

Oberek, also known as obertas (common in the 19th century), or ober (the name used less frequently), is – in its stage versions performed by Polish folk dance ensembles – the most vivacious and acrobatic of the so-called five national dances (with polonaise, mazur, kujawiak, krakowiak). The oberek originated in the villages of Mazowsze in central Poland; it is danced by couples to instrumental music in triple meter. The name oberek is derived from the verb obracac się – to spin. The dance’s main movement is rotational: the dancers spin and twirl around the room.

The term obertas appeared for the first time in 1679, in a book by Korczyński, Lanczafty. Oberek belongs to the group of dances which feature the so-called mazurka rhythms (see the entry on Mazur for an explanation of this pattern and an example). The dances include kujawiak (the slowest), mazur or mazurka (in a moderate tempo), and oberek (the fastest dance of this group). All three dances are of peasant origin, but due to contract with town people and the nobility, they all underwent considerable changes, especially the mazur and kujawiak.

The lack of clarity in the definition of the oberek and its differentiation from related dances was further increased by a variety of names that had been used in reference to it. In addition to obertas and ober, the dance was also called: obertany (from “turn”), wyrwas (from “pull out”), wykrętacz (from “turn”), drygant (related to “move”), zwijas, zwijacz (from “roll” or “twist”), drobny (from “small or “minced”), and okrągły (from “round”). These names reflect the fast tempo, circular movement, and the whirling character of the dance.

According to Oskar Kolberg (Kujawy, vol. 4 of Complete Works 1867), in central Poland dances from the family of the mazur (kujawiak, mazur, oberek) were often performed in a set preceded by a chodzony (walking dance, a folk polonaise) and organized in an increasing tempo. The set ended with a frenzied oberek (MM=160-180). According to Aleksander Pawlak, this 19th-century practice was abandoned early in the 20th century (Pawlak, 1981, 14-15). Interestingly, Pawlak’s field studies reported even faster tempi for the obereks; the majority of the melodies discussed in his study had a tempo higher than MM=190, reaching up to MM=240 (Pawlak, 1981, 141).

The oberek described by Ada Dziewanowska is a national dance “not only because it is common all over Poland, but also because it is danced by all the social strata. Different regions, however, still retain their local style, variations and their specific music” (Dziewanowska 1999, 592).

The folk dance groups often perform the national form of the oberek in the costumes from Łowicz Mazovia (the central part of the region). The State Folk Song and Dance Ensembles Mazowsze and Śląsk perform “a most artistic, but stylized rendition” of the oberek. It has also become a recreational dance growing in popularity and providing competition to the Polish American polka.

In classical music, the name oberek was used by composers of stylized dances starting with Oskar Kolberg who collected obereks from Mazovia in four volumes of his study dedicated to the Mazowsze region (vol. 24-27 of the Collected Works) and in two volumes from the Kujawy region (vol. 3-4 of the Collected Works). Kolberg’s own arrangements are in vol. 67 of his works. Other Polish composers of obereks include Henryk Wieniawski (Obertas for violin and piano, Mazurka characteristique no. 1), Roman Statkowski, Karol Szymanowski, Aleksander Tansman, and Grażyna Bacewicz (who composed obereks as self-standing works for violin and piano, as well as movements in more extended compositions, e.g. the finale of her Piano Sonata no. 2). Needless to say, the fastest Mazurkas by Fryderyk Chopin are also examples of obereks; for instance, his Mazurka op. 56 no. 2. In contrast to the mazurka, polonaise and krakowiak (cracovienne) the title oberek is very rare in the music of Western composers, and it does not occur among the titles of Polish dances composed in 19th-century America (see Janta, 1982).

Description

In Grażyna Dąbrowska’s account (Dąbrowska 1980, 149-151), oberek is faster than a mazurek; it is danced by couples who are placed on a circle and rotate both around the whole circle and around their own axis (to the right). The dancers follow the direction “against the sun” (pod słońce, counterclockwise). The strongest dancer may ask for a change of direction of the whole group which then would dance “ze słońcem” (with the sun, clockwise). The most difficult change of direction involves a simultaneous change of the rotation around the personal axis, performed to the left only by the best dancers.

At times the women turn around the men; sometimes the men vary the motion of their legs, performing a wider “twisting” gesture on the third beat. The dancers in a couple do not separate (with the exception of quick turns performed by the woman) and tend to hold their hands throughout. There are few steps to provide variety in the course of the dance; its enjoyment stems from the very fast tempo, regularity of turns and the simultaneity of changes of direction. There are no complicated acrobatic displays in the folk tradition of Mazowsze.

Dziewanowska (Polish Folk Dances and Songs 1999, p. 591) described the oberek in its national form and regional variants as “a joyful, exuberant and noisy dance with stamps and shouts.” In the national form, the basic “bouncy” step of the oberek which articulates its triple meter may be danced with a partner held in a dance position, with partners apart facing each other, or in solo dancing. The issue of separation of dancers is one of the differences between the forms of the oberek in folk practice and artistic stylization on the stage.

There are more differences between the stylized form and its model; the stage-oriented folk dance groups use many ornamental and acrobatic figures in the main form of the oberek, kneeling, heel clicking, jumping, stamping and double-stamping, lifting the partner (performed by both men and women), women jumping over the men’s outstretched leg, etc.

In addition to this elaborate form of the oberek, Dziewanowska describes also three distinct regional varieties, each of which could be performed in the appropriate costume from the region. The Łowicz oberek is danced in a less bouncy manner than the national version. It consists mainly of the couples turning around the dance area. Small flat steps are used, with little progression around the circle. In the region of Opoczno further south in Mazowsze, the oberek is danced faster and with more bounce and vigor than in the other parts of Poland. In the Lublin oberek (east of Mazowsze, central and south-central Poland), the dance was often interrupted with couplets improvised on the spot, in which the dancers would tease each other.

Costumes

The costume of choice for the oberek is the colorful striped costume of the Lowicz area. Women wear wool skirts made of striped cloth woven from vivid hues over layers of white petticoats finished with lace and ruffle.

Their white shirts have elaborate white embroidery and are covered with tight vests embroidered with flowers. They wear bright kerchiefs wrapped around in elaborate patterns and long braids with ribbons. The men wear pants made from the same striped cloth, high black boots, long dark vests and white shirts. The costumes are extremely rich in color and ornaments – hence its popularity among Polish American folk dance groups.

The rise to prominence of the Łowicz costume may be associated with its use by the State Folk Song and Dance Ensemble Mazowsze which seems to have preferred the vivid Łowicz stripes and flowing skirts for its promotional literature.

In Kolberg’s Mazowsze, the description of the costumes was different, the colors more subdued, the ornaments less obvious (Kolberg 1885, p. 34, 49-54). According to the ethnographer, the costumes, made of rich, thick cloth, revealed the affluence of their peasant owners. Men were covered with their long, thick coats (sukmana) which were either white or navy with dark red trimmings. Women wore longer skirts than the folk group dancers (floor length, not below the knees).

The image on the left depicts folk costumes from the area of Warsaw, according to Kolberg; notice the woman’s flowery reddish skirt covered by a blue-white striped apron. (Contemporary folk dance groups rarely use horizontal stripes on their skirts or aprons). She wears a scarf tied in an elaborate head wrap. Variations of this headdress are common, though the modern versions are more symmetric.

The man is a farm-hand (he is barefoot), his sleeveless jacket reaches his knees, his pants are tight and white, without bold colors or patterns.

The only element of the costume that survived without major modification is the shape of the woman’s vest which is tied with a ribbon in the front and adorned with the characteristic folds around her waist (the vest is cut into 8 overlapping pieces with red trim).

While the differences between the costume from the two Mazowszes – the one described by Kolberg and the one performed by the State Folk Song and Dance Ensemble – might be attributed to local variations of the regional costume, Kolberg’s description of the Łowicz costume itself strikingly varies from the varieties popular today. Instead of a colorful striped cape, the women had long, navy coats covering their long navy vests (hip-length) and striped skirts (predominantly red and white). Their red kerchiefs were tied around the head with the knot in the front. The rainbow coloring and rich embroidery of the modern-day folk costumes simply was not there.

The popularity of the Lowicz costume notwithstanding, the obereks from other areas of Poland might be danced in regional costumes, for instance the Lubelski costume used by the Krakusy Polish Folk Dance Ensemble in 1999. Unlike the mazur, to which the oberek is musically related, in current performance practice the oberek is never danced in costumes of the nobility or the army (see the entries on Mazur and Polonaise for descriptions of these costumes). Thus, its status as a truly “folk” dance is affirmed. This association between oberek and Polish villagers, especially from the Lowicz area, is reinforced by the popular woodcut by Zofia Stryjenska (1927), here represented from its copy on the cover of an LP Polka Dance Melodies recorded by Ted Maksymowicz and his Orchestra, (LP, ABC Paramount, ABCS 289; n.d.).

Music

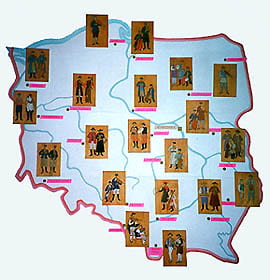

In central Poland, the music for the oberek was typically performed by a small village band, kapela, dominated by the violin. The size and exact make-up of the kapela depended on the part of the region from which it originated. The map of Poland reproduced below indicates the dominance of the violin as the main instrument in Polish folk ensembles in the whole country, not just in the Mazowsze region (the map is in the collection of the Museum of Musical Instruments in Poznań).

In the northern Płock Mazovia the group consisted of a violin and large drum and a folk accordion (harmonia trzyrzędowa); in the central Łowicz Mazovia area these three instruments were often joined by the clarinet. In the Skierniewice area the typical ensemble included the violin performing the highly ornamented variants of the melody in numerous repeats, the three-string basy (for a picture and description see the entry on kujawiak) providing the percussive accompaniment, and a small side drum with jingles, also enriching the percussive part. Later on, the folk accordion was sometimes added.

Musicians from the Skierniewice area featured the largest number of fast-paced obereks in their repertoire (in comparison with other parts of Mazovia).

The accompaniment for the dance was inseparably connected with singing. The musicians respond to the initial couplet sung by a soloist who “calls on them” to play, at times mocking their skills and ridiculing their poverty, at other times teasing other dancers and participants in the social occasion. The obereks were often danced in wedding celebrations and a variety of texts contain sexual overtones. A notable feature of the sung oberek is the presence of meaningless syllables and phrases, which may imitate the sound of the instruments, express the vigor and enjoyment of the dancers, and have other functions. The most popular of these exclamations are: oj dana, dana, , or uch, ucha-cha, or oj dziś, dziś. The latter expression which means “oh, today, today” is – in Dziewanowska’s explanation – either an imitation of a percussion instrument, or “it conveys the typical trait of the Polish character, that today we live and are merry, and who cares what tomorrow might bring” (Dziewanowska 1999, 591). Notice the presence of the old-fashioned stereotyping of the “national spirit” in this description.

The music includes the same type of mazurka rhythms as the kujawiak and mazur. Due to the very fast tempi, tempo rubato is almost non-existent. In instrumental obereks the longer notes of the melody are filled in with fast-paced sixteenth-note figuration, often following the outline of a triad arpeggio. The lead violinist shows off his skill by playing ever new variants of the same melody; the tempo is either steady, or gradually increases towards the end of the dance, making the performance (both the musicians and the dancers) more and more virtuosic.

Each phrase of the music usually consists of 4 or 8 measures and they are grouped in pairs. The main accent usually falls on the third beat in each measure. As mentioned above, the oberek is the quickest of the five national dances and in folk performances reaches dizzying speeds.

Sources of Materials

- Dąbrowska, Grażyna. Taniec ludowy na Mazowszu [Folk dance in Mazovia]. Kraków: PWM Edition, 1980.

- Dziewanowska, Ada. Polish Folk Dances & Songs: A Step by Step Guide. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1999.

- Harley, Maria Anna. “Dance as a National Symbol: Polish Dance in Southern California.” Project for Southern California Studies Center at USC, August 2000.

- Janta, Aleksander. A History of Nineteenth Century American-Polish Music New York: The Kosciuszko Foundation, 1982.

- Kolberg, Oskar. Mazowsze Polne in Dzieła Wszystkie [Complete Works], vol. 24-5. Wrocław-Poznań: Polskie Towarzystwo Ludoznawcze, 1963. Reprint of a 1885 publication.

- Lange, Roderyk. “Kinetography Laban (Movement Notation) and the Folk Dance Research in Poland,” Lud 50 no. 2 (1966): 378-391.

- “Oberek,” entry in Encyklopedia Muzyki PWN Warszawa: PWN, 1994.

- “Oberek,” entry in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, vol. 15. Stanley Sadie, ed. London: McMillan, 1980.

- Pawlak, Aleksander. Folklor Muzyczny Kujaw [Musical folklore of Kujawy]. Kraków: PWM, 1980.

- Sources of Polish Folk Music / Muzyka Źródeł, vol. 1, Mazowsze. Notes. Polskie Radio CD PRCD 151, 1996.

Illustrations from Polish folk art (straw cutouts); Zofia Stryjeńska’s 1927 “Oberek” image (from the cover of LP Polka Dance Melodies, Ted Maksymowicz and his Orchestra. ABC-Paramount, ABCS-289, n.d.); photographs from PMRC Collection and from archival material gathered for M.A. Harley’s Polish Dance in Southern California project.