Essay by Maja Trochimczyk

History

The Polish folk dance zbójnicki is an energetic men’s dance from the Skalne Podhale area (the rocky foothills of the Tatra Mountains and the Tatras themselves, located in southern Poland, bordering on Slovakia and Moravia). The name is an adjective created from the noun zbójnik – a brigand or a robber; plural – zbójnicy. In the 17th-18th centuries, bands of such robbers thrived in the Tatra Mountains; they came from Górale villages of the area. The practice started in the 12-13th centuries, and after peaking in the 18th century, was suppressed by the Austrian government – according to historians quoted in the entry about this phenomenon, zbójnictwo in the Słownik Folkloru Polskiego (Dictionary of Polish Folklore, Julian Krzyżanowski, ed. Warszawa: Wiedza Powszechna, 1965).

These robber bands included highlanders who were trying to escape from the oppression of the lords or avoid military service, and peasants from other parts of Poland who wanted to evade the burden of serfdom, as well as various outlaws and individuals seeking adventure or hoping to find the legendary treasures hidden in the Tatra Mountain caves. In the mountain enclaves there were groups of brigands from Podhale, Silesia, Moravia and Slovakia. The bands pillaged manor houses, farmers, mills and cottages, taverns and coaches of travelling merchants.

The robbers evoked terror but also admiration and envy for their courage, freedom and wealth. Their most famous leader was the son of a Slovak peasant, Juraj Janosik. The historical Janosik became a legendary hero both on the Slovak and the Polish sides of the Tatra Mountains, and facts from his life were intertwined with folk legends and stories about the “idealized bandit,” or “good robber.” Janosik was born in 1688 in the village of Terchova in Orawa; his band was active in Slovakia and Hungary. According to the legend, as recounted in the entry on zbójnicki by Ada Dziewanowska (Polish Folk Dances and Songs. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1999), he had a generous heart and, like Robin Hood, robbed the rich but shared his wealth with the poor and protected them. In the end, as the legend has it, a jealous girlfriend betrayed him to the Austrian gendarmes. They captured him and took him to Orawa Castle, where he was hanged in 1713 (he was only 25 years old). The wide-spread admiration for Janosik and other zbójnicy among the villagers in the Tatra Mountains was expressed in the creation of many stories, poems, and songs describing their deeds, and bravery. They also became a subject for artists (Włodzimierz Skoczylas), writers (Kazimerz Przerwa-Tetmajer, Gustaw Morcinek), and composers (Karol Szymanowski – the ballet Harnasie. There are no robbers in the Tatra Mountains now, but Polish culture carries their memory. The dance form of zbójnicki stylizes the highland robbers’ physical stamina and bravado.

Description

The dances of the highland robbers, for male dancers only, appear in different versions and under different names in the folklore of the Poles (the Górale culture of the Tatra Mountains), Slovaks, and Ukrainians. Formerly, the zbójnicki used to be danced by the shepherds when they took their flocks to mountain pastures.

According to Timothy Cooley (notes for Fire in The Mountains CD, Yazoo 7013, 1997), the dance probably originated on the Slovak side of the Tatras. Today, it is usually done for exibition, either for the enjoyment of the local people, or (mainly) for visitors and tourists. Even today the performers do not consult professional choreographers but arrange the dance themselves, following the traditional sequence.

Dziewanowska (Polish Folk Dances, 1999), claims that in comparison to the góralski dance most of performers find the zbójnicki easier to learn because of its more obvious rhythm, and if the performer is in good physical condition, its steps are not as difficult to master.

Another advantage of the zbójnicki is that, because of its many steps and figures, it can be arranged to best suit the level of given ensemble. The zbójnicki can be danced by an even number of men (not less than four), one of them should be chosen as the harnaś-leader. The harnaś first calls ” Hej, chłopcy, zbójeckiego!” (Hey boys, lets dance the zbójnicki), and the dance starts with the men walking as if to warm their muscles. The walk is energetic, following the “bouncy” rhythm of the music.

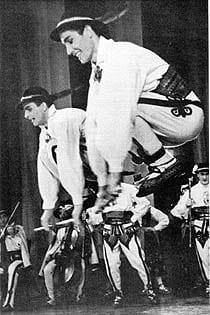

Then the dancers stop in a semi-circle and sing, stepping sideways from one foot to another. Next, they walk again, and at the call of the leader, perform one of the zbójnicki’s spectacular figures (leaps, squatting figures); then they walk and/or sing some more. Thus, the performers keep interchanging the zbójnicki’s spectacular movements with “rest periods.”

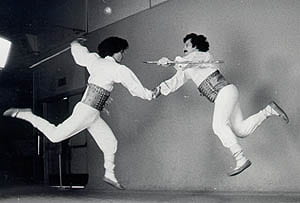

Some of the figures portray dancing around an imagined, centrally-located bonfire. The dancers leap through the central point of the circle; they also pair up and strike their ciupagas (mountain hatchets, see the description of the costume below), stand in two rows throwing the ciupagas to each other, jump over the ciupaga held in both hands, etc. At the end, they hook elbows and turn in pairs (in place, around their axis); then while singing another tune, they leave.

Costumes

Dziewanowska advises that the dancers should wear the full górale outfits, including the hat, the wide belt, and the kierpce (moccasins), and hold the ciupaga in their right hand. The ciupaga, a mountain hatcher, has a long handle made from the ash tree, with a pointed metal spike at the bottom and a steel sharp ax at the top. Both the handle and the ax are ornamented with metal; small metal ringlets that jingle when the ciupaga is shaken are attached on the upper side of the handle. The ciupaga served as a help in mountain climbing, as a defense tool against wild animals, such as bears, and as a weapon in a fight. Nowadays it may be used as a walking stick, as an ornament requisite in dancing, and a house-decoration or souvenir.

Some dance groups introduce a straight headdress with ornamental decorations (similar to the one depicted in the illustration by Stryjeńska above; such fanciful hats appear in performances of the Chicago-based The Lira Dancers). Most often though, the dancers use the standard flat, round hats, with a narrow rim and a small band of ornamental seashells, with a feather on the side.

The costume’s pants and jackets are made of rough white wool (appropriate for the severe climate of the mountains), with embroidery incorporating motives of the parzenica which is a characteristic of the folk art in this region.

Music

The music of the Górale folk tradition is usually performed by a small string ensemble, resembling the make-up of a string quartet: a lead violin performing ornamental melodies, two accompanying violins, and a three-stringed basy, providing the harmonic basis for the chords. The basy is smaller than the double-bass, roughly the size of a cello. The second violin and the basy play rhythmic quarter-notes in duple meter with strong accents, providing the rhythmic framework for the music. In the nuta zbójnicka (the zbójnicki tune), the rhythm is upbeat and lilting; in Timothy Cooley’s words “the accompanying violins bow downward on each beat with the basy and add an up-bow in-between each beat (1&2&1&2&1&2), effectively playing twice as fast as the basy.” (from Fire in the Mountains CD, Yazoo 7013; 1997, p. 8-9). Another common instrument used in the area was a simple carved string instrument resembling a basic fiddle, called “złóbcoki.” Four different złóbcoki from the collection of the Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw are shown below (photo by M.A. Harley, 1997).

The zbójnicki tunes use the so-called Podhalean scale as the source of pitch material; its characteristic raised fourth (“the Lydian fourth”) is most often singled out as the main trait of Polish folklore from the Podhale area. It has been imitated by composers in many stylizations of this music. It is this rhythm that distinguishes the zbójnicki music from other musics performed by the same type of ensemble. In the past, the lead violinist sometimes performed on an indigenous instrument, a small “pocket-violin” called złóbcoki (i.e. “carved ones,” referring to the fact that the instrument was made from one piece of wood; others derive this name from the term “łób” – the cradle).

Excellent archival recordings of fiddlers and ensembles performing zbójnicki and other melodies from the Podhale area may be found in a series of recordings issued by the Polish Radio, Sources of Polish Folk Music / Muzyka Źródeł, vol. 2, Podhale; Polskie Radio CD PRCD 151, 1996 (available from Polish Art Center, and other distributors online). Archival recordings of highland bands active among Polish Americans are reissued in Fire in the Mountains CD, Yazoo 7013, 1997 (available from Amazon.com). In Poland, various górale bands have also issued their own recordings on CD (Kapela Staszka Maśniaka, kapela Zakopiany, Trebunie “Tutki,” and others).

Sources of Materials

- Dziewanowska, Ada. Polish Folk Dances & Songs – a Step by Step Guide. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1999.

- Cooley, Timothy. Notes for Fire in the Mountains CD, Yazoo 7013; 1997.

- Harley, Maria Anna. “Dance as a National Symbol: Polish Dance in Southern California” Project for Southern California Studies Center at USC, August 2000.

- Kleczyński, Jan. “Melodie zakopiańskie i podhalańskie” [Melodies from Zakopane and Podhale]. In Pamiętnik Towarzystwa Tatrzańskiego 1888, p. 39-102. Reprinted in Oskar Kolberg, Dzieła Wszystkie [Complete Works], vol. 45, “Góry i Podgórze II.” Wrocław-Poznań: Polskie Towarzystwo Ludoznawcze, 1968, 447-493.

- Sources of Polish Folk Music / Muzyka Źródeł, vol. 2, Podhale. Notes. Polskie Radio CD PRCD 151, 1996.

- Zbójnictwo, entry in Słownik Folkloru Polskiego (Dictionary of Polish Folklore) Julian Krzyżanowski, ed. Warszawa: Wiedza Powszechna, 1965.

Illustrations from Polish folk art (straw cutouts); Zofia Stryjeńska’s 1927 “Zbójnicki” image; photographs from PMC Collection and from archival material gathered for M.A. Harley’s Polish Dance in Southern California project.