Bogurodzica [Mother of God], 13th c., Polish

Gaude, Mater Polonia [Rejoice], 12-14th c., Latin

Mazurek Dąbrowskiego [Dąbrowski Mazurka], 18th c.

Boże, coś Polskę [God Save Poland], 19th c.

Rota [The Oath], 20th c.

Introduction: A Brief History of National Anthems

by Maja Trochimczyk

The English term “national anthems” has a Polish equivalent of “state hymns” – and both terms have the same meaning if the nation and the state are one; if not – and this happened in Polish history – important differences arise, some of which will be discussed here. While the British hymn God Save the King/Queen (first printed in the middle of the 18th century) is often described as the earliest national anthem, it should be, rather, called the first “state anthem.” It was preceded by many earlier national hymns, including the Polish Bogurodzica/The Mother of God which originated as far back as the 13th century. This ancient chant, one of the earliest written documents of the Polish language, has a firm place in Polish cultural history.

Bogurodzica is a religious hymn, a simple prayer for personal happiness on earth and for a blessed life in heaven. It is addressed to Mary asking her for intercession and it does not mention issues of national identity. Nonetheless, this beautiful, quiet chant served the country as its anthem and was called, for instance by Jan Długosz, “carmen patrium”/the song of the homeland.”

It was sung by the Polish troops in the battle against the Teutonic Knights held at Grunwald in 1410 (one of the landmark events in Polish history, defending national independence) and served as a coronation anthem for the Jagiellon dynasty of Polish kings through out the sixteenth century. According to the research of Professor Hieronim Feicht, whose extensive essay on this topic appears in Studia nad Muzyką Polskiego Średniowiecza/Studies of the Music of the Polish Middle Ages [Krakow: PWM Edition, 1975], Bogurodzica has textual links with the Czech Republic and Eastern Christianity, and musical links with early French songs, folk music and the plainchant of the Latin Church.

This “hymn of the nation” must have been very popular, since despite the many wars that ravaged Poland, it survived in sixteen manuscripts dating from the period between the 15th and the 18th century. Another religious song that in time became a patriotic anthem associated with the historical traditions of the Polish state was Gaude Mater Poloniae.

This beautiful anthem is dedicated to the memory of bishop St. Stanislaus, killed by the king Bolesław Smiały in the early 11th century. Stanislaus is one of the patrons of Poland. The fact that this anthem was mostly disseminated with its Latin text prevented it from becoming a true symbol of the country; the Polish Bogurodzica continued to fulfill this role for many centuries.

During the partitions (19th century), Bogurodzica was usually printed in patriotic-religious hymnals as the first, most ancient and revered song, followed by Boże coś Polskę/God save Poland, Z dymem pożarów/With the smoke of fires, and Dąbrowski Mazurka. To this day, Bogurodzica is sung in Polish churches, serving the religious and aesthetic needs of the people. The ornamental melody of haunting beauty is too difficult for amateurs, but hearing it performed by professional singers, nuns, or monks, is an unforgettable experience. Composer Andrzej Panufnik was so impressed with its solemn grandeur that years after hearing it the wrote a symphony based on and dedicated to Bogurodzica, entitled Sinfonia Sacra (1963). Another contemporary composition based on this melody is Marta Ptaszyńska’s Conductus – A Ceremonial for Winds (1982).

In the 17th and 18th century, Poland did not have a royal dynasty that would ensure a continuity of rule; the kings were elected by all the gentry gathering for Seyms [National Assemblies], and the country was gradually disintegrating into chaos. While Poland was losing its political power and cultural strength, the symbols of its statehood also changed: a variety of songs were sung to replace Bogurodzica, none of them notable or well remembered. However when Poland reached the lowest point in its history, during the partitions at the end of the eighteenth century, a resurgence of interest in defining and protecting national identity led to the creation of a number of songs which, in time, competed for the title of the “national anthem.”

In 1774 the patriotic poet-bishop Ignacy Krasicki wrote a hymn to “Holy Love of the Beloved Homeland” which is sung to this day at the Military Academy [Szkoła Rycerska]; and appropriately so, since it calls for ultimate sacrifices for the sake of the country, including the offerings of poverty and death. Krasicki’s subsequent hymn, written for the first anniversary of the proclamation of the 3rd May Constitution (in 1792), is more joyous in nature and is set to a popular, memorable melody. Either of these songs could have become the Polish anthem had the country survived and had the Constitution remained its highest law. Unfortunately, history proved otherwise; and the hopes felt at the moment of defining the country’s first fully democratic Constitution gave way to disillusionment and despair when Poland was divided by Russia, Prussia and Austria in a series of partitions (1773, 1791, 1795), the last of which removed the country from the map of Europe.

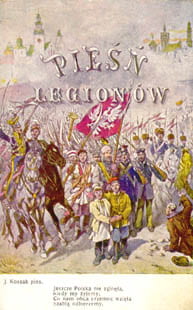

Not all was lost, of course, and Poles gathered to fight for their country’s independence assisted through out this struggle with song. This is when the current Polish national anthem, entitled Dąbrowski’s Mazurka, came into being. In 1797 General Józef Wybicki, who was a member of the Polish troops which served Napoleon in Italy and Spain, penned a song to bid farewell to the departing Polish army. The Polish Legion, led by General Dąbrowski, had hoped to come with the Napoleonic troops “From Italy to Poland” to liberate their country, and the Mazurka’s text made this hope explicit. The troops fought and won with Napoleon, and a short-lived “Duchy of Warsaw” was born from this hope, to die in 1815 for the next one hundred years.

The first line of the text states that “Poland is not dead, as long as we live” and Poles continued to sing these words through the 19th century while struggling for their country’s reemergence. Thus, Napoleon Bonaparte became immortalized in Poland’s national anthem… Another unusual fact relates to the anthem’s music, the traditional melody of a swift mazurka. In the 19th century a variant of this mazurka became a pan-Slavonic hymn Hey Slovane which in 1945 was declared the national anthem of Yugoslavia. Now of course, it no longer serves this function. It is interesting to notice that the two melodies are virtually indistinguishable except for the first three notes.

The Dąbrowski Mazurka was declared the official anthem of the country in 1926, after Józef Piłsudski took control of the country. Poland had been independent since 1918, and had no official anthem for the first eight years of its existence. The valiant Mazurka became a winner in a competition for the position of the national anthem with several other revered songs: Chorał, Rota, and Boże coś Polske.

The Choral [“With the Smoke of the Fires”] by Kornel Ujejski (1846) expressed sorrow at the peasant’s uprising of 1846, with a prayer that such events from which “one’s hair turns grey” – as the first strophe has it – would never happen again. With its first line “with the smoke of the fires, and with the dust of fraternal blood” it was, perhaps, not an appropriate text to celebrate Poland’s independence – although it served as a national hymn in the Austrian part of the divided country. Another candidate, Rota, by Maria Konopnicka (1908) to music by Feliks Nowowiejski (1910), was also too limited in scope. This song expressed the sentiments of the Polish farmers in the Prussian-occupied part of Poland who were forced off their land: “We shall not leave the land of our forebears” they sang in resistance. Rota became very popular after 1910, the year when the Grunwald Monument was unveiled and anti-German feelings reached their peak.

Finally, the most serious contender for the role of a national anthem was the hymn God save Poland by Antoni Feliński (1816). With its refrain of “God bless – or liberate – our homeland” it is still a very popular prayer for the country sung in all Polish churches.

It became a hymn of the nation during the January Uprising against the Russians in 1860-63, but its origins do, paradoxically, link Poland and Russia. The hymn’s original refrain stated “God bless the King” – meaning Tsar Alexander the First, who, after the defeat of Napoleon, became the first ruler of a newly established Kingdom of Poland. The original text was soon changed by replacing “King” with “homeland” and the song became so popular in the patriotic movements that its origins were forgotten. After 1863, it was banned in the Prussian and Russian-occupied parts of Poland; it was banned, one should add, because it had served as the anthem for the January Uprising. Despite the repressions, the hymn never lost its popularity.

Even in 1928, two years after the declaration of Dąbrowski’s Mazurka as the official anthem of the country Boże coś Polskę was labelled “hymn narodowy”/”national anthem” in a hymnal of the Catholic Church [X. Jan Siedlecki: Śpiewnik Kościelny z Melodjami na 2 Głosy/Church Songbook with Melodies in Two Voices. Lwów-Kraków-Paris: Priests Missionaries, 1928].

After World War II Dąbrowski’s Mazurka continued to serve as the official anthem of Poland, reminding Poles of the duty to be active for the sake of their homeland. Its affective power was not diminished by its use by the generally disliked socialist government. However, the Solidarity movement chose another song for its unofficial hymn: Żeby Polska była Polską/Let Poland be Poland by Jan Pietrzak (1976). Written after the unrests of Radom and Ursus it is not a call to armed struggle and not a prayer for the country, but rather a meditation on the past wars fought by generations of Poles to “Make Poland, Poland.”

How does the Polish anthem relate to the musical symbols of other countries? Dabrowski’s Mazurka belongs to a type of anthem-march that is generally associated with the French anthem, La Marsellaise, written for the marching troops of the French revolution. These marches are usually fast and energetic, filled with enthusiasm for the new world order that their texts call for. While the Polish anthem shares these features of a “call to arms” to fight for Poland’s independence, it is a swift, boisterous dance in a triple meter, not a steady march.

Interestingly, foreign orchestras often perform the Mazurka in a slow fashion, transforming its joyful reassurance that Poland still lives in us, into a sort of a funeral march. There is a reason for it, because many national anthems belong to a category modelled upon the British God Save the King/Queen – a prayer for blessings to be bestowed upon the monarch. These hymns are usually very solemn, instilling in their listeners a profound devotion for their country. Some of their textual variants describe the beauty and riches of the land, instead of enumerating the virtues of the monarch.

The countries of Latin and Southern America have hymns of a different type, resembling Italian operatic arias. Some of these arias have actually been written by Italian composers. The rule seems to be: the smaller the country, the longer and more elaborate the anthem, with more different parts, longer orchestral introductions. Not surprisingly, El Salvador’s anthem is the longest. South and American countries are also very serious about the legal protection of their anthems. In Brazil, for instance, it is a criminal offense to perform the national anthem in a different tempo and a key different from that officially prescribed. A singer once had the bad luck of intoning the anthem too high and too fast; she was saved from imprisonment only because she thus celebrated the election of the new president of the country. Luckily, Polish authorities do not arrest anyone for singing off-key. And with that thought let me finish this brief exploration of the convoluted history of Polish national anthems.

NOTE: This essay originally appeared in the May 1997 issue of the PMC Newsletter. A longer study of the same subject entitled “Sacred versus Secular: The Convoluted History of Polish Anthems” appears in After Chopin: Essays in Polish Music, ed. Maja Trochimczyk, vol. 6 of Polish Music History Series (Los Angeles: Polish Music Center at USC, 2000). Postcards from Maja Trochimczyk Collection.