Essay by Maja Trochimczyk

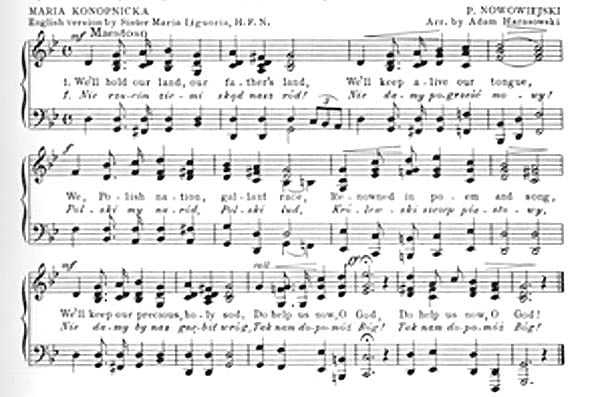

Rota is the youngest of the famous Polish national songs: it was created in the 20th century. The song’s text was written in 1908 by Maria Konopnicka; the music added two years later by Feliks Nowowiejski.

Konopnicka’s poem was a protest against the Prussian legislation that introduced a gradual expropriation of Polish land owners in the Prussian partition of Poland (remaining under Prussian occupation in 1795-1918).

The final partition took place after the failure of the Kosciuszko Insurrection of 1794 (the Insurrection is depicted here in Juliusz Kossak’s illustration for Dabrowski Mazurka; note the peasants’ costumes and their weapons converted from farming tools, i.e. scythes).

The text expressed the sentiments of the Polish farmers in the Prussian – occupied part of Poland who were forced off their land: “We shall not leave the land of our forebears” they sang in resistance.

Rota was inspired by the events taking place in the Wielkopolska province marked by protests and acts of the peasants’ passive resistance (they were not allowed to build houses so some lived in 19th-century versions of “mobile homes”). The song was first published in the Cracow paper “Leader” (1908 – Kraków, the capital of Galicia, was in the Austrian partition where Poles enjoyed more autonomy).

The strongly anti-German poem soon became very popular throughout the country; the way to this widespread popularity was paved by its elevated role during the celebrations of the 500th anniversary of the Battle of Grunwald (1410-1910).

In January 1910 Feliks Nowowiejski wrote the music to the Konopnicka’s poem and on July 15, when the Grunwald Monument in Kraków (capital of Galicia, Austrian partition of Poland enjoying more autonomy than the other two parts of the divided country) was unveiled, choirs from all over Poland, conducted by the composer, performed the song for the first time. For this occasion the song was entitled Grunwald; in print it appeared as Signal. It is important to note, though, that the version of Rota heard during the Grunwald celebrations is not the same as the one known today. The composer changed the melody and some chords in the accompaniments before publishing a new version, which is being used until the present time.

Text Fragment

We shall not abandon the land of our ancestors!

We shall not allow to bury our language!

We are the Polish nation, the Polish folk,

We are the royal descendants of Piast,

We shall not allow the enemy to opress us,

So help us God! So help us God!

Germans will not spit in our faces,

they will not germanize our children,

our troops will stand with weapons,

the peasants will be our leaders,

We shall go when the golden horn will sound –

So help us God! So help us God!

We shall not abandon the land of our ancestors!

We shall not allow to bury our language!

We are the Polish nation, the Polish folk,

We are the royal descendants of Piast,

We shall not allow the enemy to opress us,

So help us God! So help us God!

Germans will not spit in our faces,

they will not germanize our children,

our troops will stand with weapons,

the peasants will be our leaders,

We shall go when the golden horn will sound –

So help us God! So help us God!

Sources of Material

- This entry is based on Maja Trochimczyk’s essay “Sacred versus Secular: The Convoluted History of Polish Anthems,” in After Chopin: Essays in Polish Music, ed. Maja Trochimczyk, vol. 6 of Polish Music History Series (Los Angeles: Friends of Polish Music at USC, 2000).

- The recording is from Boze, cos Polske CD, performed by State Folk Dance Group Mazowsze, issued by Polskie Nagrania, ECD 034.

- The score included above is from Treasured Polish Songs with English Translations, ed. Josepha K.Contoski (Minneapolis: Polanie Publishing Co., 1953).

- The photos and 19th-century postcards of symbolic imagery and Polish emblems are from Maja Trochimczyk Collection.