by Anna Maslowiec [1]

Abstract

The following analysis examines five major works written between 1965 and 1971: Refrain (1965) and Canticum graduum (1969) for orchestra, Old Polish Music (1967-69), Muzyczka II(1967) for large ensemble, and Ad matrem (1971) for soprano, mixed choir and orchestra. These five works retain many traces of Górecki’s interest in serial technique and clusters during the late fifties and early sixties. Yet they introduce important new features such as rhythmic and harmonic palindromes, harmonic mirrors, whole-tone scales and the use of dynamics to shape form, all of which became integral to much of his later work after Ad matrem. Refrain is examined in greatest detail for two reasons: firstly, as the most “schematic” of these pieces, it is the logical starting point for demonstrating the individual structural elements; secondly it clearly illustrates the process of building form with these elements. Refrain is the first work in which these compositional ideas are extensively worked out, and thus the first mature example of these new techniques. Although the pieces following Refrain originate from different ideas, they nonetheless, to a greater or lesser degree, share similar structural elements such as textural contrast, dynamics, palindromes and sections divided by general pauses. However, the relationship between these elements becomes flexible rather than fixed. Coming after a long interest in instrumental pieces, Ad matrem is the first work to return to the more expressive combination of voic e and text as well as anticipating a return to major-minor scales. Ad matrem concludes the period in which Górecki was preoccupied with an avant-garde interpretation of “the utmost economy of musical material” and points to the new, modally orientated direction he was to pursue in subsequent works. [Anna Maslowiec]

Article

The emergence of Henryk Mikołaj Górecki (born 1933) as a leading Polish composer in the sixties,[2] closely linked to the first Warsaw Autumn Festivals (1956-), is now largely eclipsed by his recent popularity as the composer of the Third Symphony (1976). However, the path to the Third Symphony can be traced back to the mid-1960s, a fascinating period in Górecki’s compositional output which has received little scholarly attention.[3] From the start, Górecki’s work was typified by what the composer subsequently called the “utmost economy of musical material”[4]—that is, the use of deliberately restricted music materials—and this has remained a feature of his work in the seventies and beyond, despite major changes of harmonic idiom.It was in the midst of a primarily cluster-oriented period, typical of the Polish avant-garde in the early sixties, that modal and triadic structures as well as elements drawn from medieval Polish music appeared in Górecki’s music for the first time; The Three Pieces in the Old Style written in 1963 anticipated the “white note” modal idiom of works written after 1971. However, the first work to clearly move towards the style that came to be known as “new simplicity”[5] was Refrain, written in 1965.The following analysis examines five major works written between 1965 and 1971: Refrain (1965) and Canticum graduum (1969) for orchestra, Old Polish Music (1967-69), Muzyczka II (1967) for large ensemble, and Ad matrem (1971) for soprano, mixed choir and orchestra, which concludes this period and simultaneously “opens a new phase in which, for the majority of works, the text provides an aesthetic basis and has a decisive impact on the character of the music.”[6]These five works retain many traces of Górecki’s interest in serial technique and clusters during the late fifties and early sixties. Yet they introduce important new features such as rhythmic and harmonic palindromes, harmonic mirrors, whole-tone scales and the use of dynamics to shape form, all of which became integral to much of his later work after Ad matrem. Refrain will be examined in greatest detail for two reasons: firstly, as the most “schematic” of these pieces, it is the logical starting point for demonstrating the individual structural elements; secondly it clearly illustrates the process of building form with these elements. Refrain is the first work in which these compositional ideas are extensively worked out, and thus the first mature example of these new techniques.Palindromes are the principal structural elements of Refrain. The word “palindrome” applies here to symmetrical numerical structures, for example 5-3-5, which are apparent either in the internal structure of a single measure, or the relative lengths of several measures. These could also be regarded as “mirror forms;” however, in this paper, the word “mirror” will mainly be used to describe vertical elements, for example chord structures symmetrical around a central pitch axis.[7] The piece consists of three main sections: a fast central section enclosed by two slow outer sections that are related through texture and dynamics. Within these sections, there are smaller formal sections separated by general pauses, a feature characteristic of many works that followed Refrain.

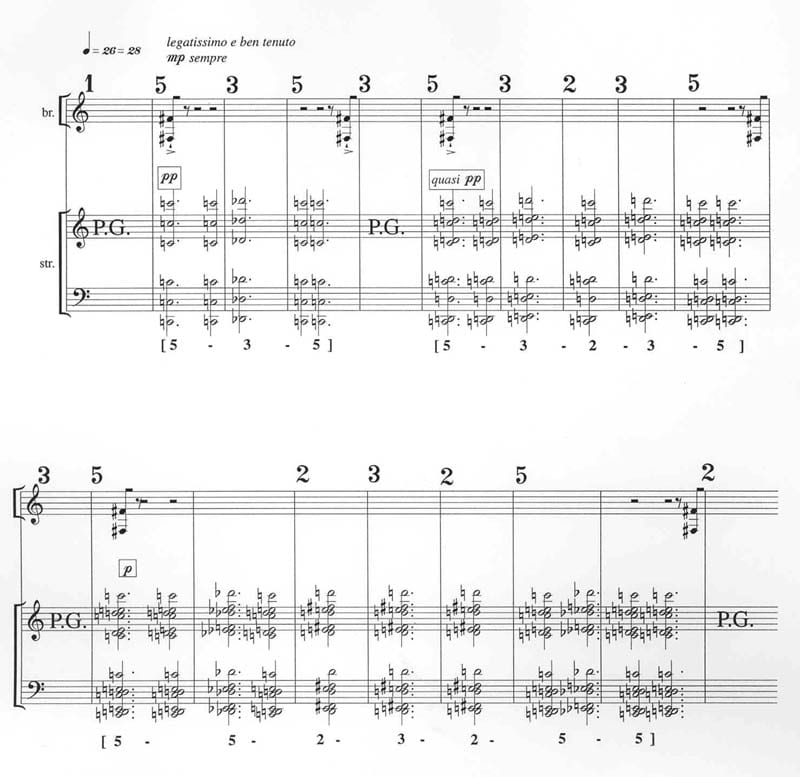

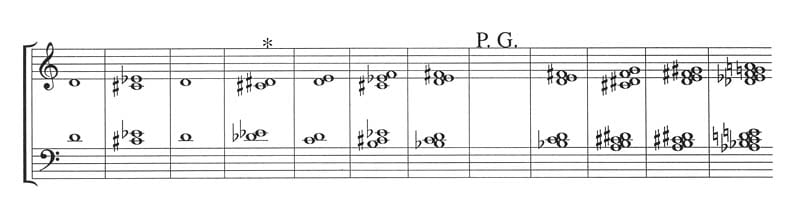

The opening section (see Example 1) consists of six “refrains,” each separated by a general pause. Each of the “refrains” is a rhythmic and harmonic palindrome, in which the harmony is reversed after the central point of the rhythmic palindromes. The rhythmic palindromes of the opening section are based on units of one to six beats in a measure. Beginning with a three-measure palindrome (5+3+5 beats), the first five refrains develop by generally extending the number of measures in each palindrome, up to 13 measures, although the longest one is the fourth, not the fifth; Table 1 shows the palindromic measure lengths. The rhythms within each measure also form an overall palindrome: 5-3-5 equals (3+2)+3+(2+3) quarter notes. In these palindromes, Górecki uses Fibonacci numbers but they do not play a significant systematic role. The fifth refrain is an inexact palindrome in that it is extended by an extra measure of two quarter notes.

| 1st refrain: | (1) – 5 – 3 – 5 – (3) – [Rhythmic palindrome] P.G. C – Db – C – P.G. –[Harmonic palindrome] |

| 2nd refrain: | 5 – 3 – 2 – 3 – 5 – (3) C – D – C – D – C – P.G. |

| 3rd refrain: | 5 – 5 – 2 – 3 – 2 – 5 – 5 – (2) C – Db- C – D – C – Db – C – P.G. |

| 4th refrain: | 3 – 2 – 3 – 6 – 1 – 3 – 2 – 3 – 1 – 6 – 3 – 2 – 3 – (3) C- Db-C- D- Db-Eb-D– Eb-Db-D- C-Db- C – P.G. |

| 5th refrain: | 3 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 1 – 4 – 3 – 2 – 3 – 2 (3) C- D- C- Db- Db– Db- C- D- C- C – P.G. |

Numbers designate the number of beats in a measure; the number and pitches in bold type mark the center of the palindrome. Numbers in parentheses refer to the number of beats in silent measures whilst letters indicate the bottom pitch of the chords.

The sixth refrain comprises two palindromes, separated by a three-beat measure (see Table 2). The beginning of the first palindrome of the sixth refrain is identical to the first refrain. With slight variations both palindromes are repeated in the coda. The second palindrome is extended by a two beat measure followed by a 5-3-5 palindrome to conclude the whole piece. Thus the two palindromes of the sixth refrain can be regarded as a microcosm of the whole piece.

| 1st palindrome: | 5-3-5-6-5-5-5-5-5-6-5-3-5-3 |

| 2nd palindrome: | 6-3-3-6-3-3-6 |

| coda: | 5-3-5-6-5-5-5-5-5-6-5-3-5 2-6-3-3-6-3-3-6-2-3-5-3 |

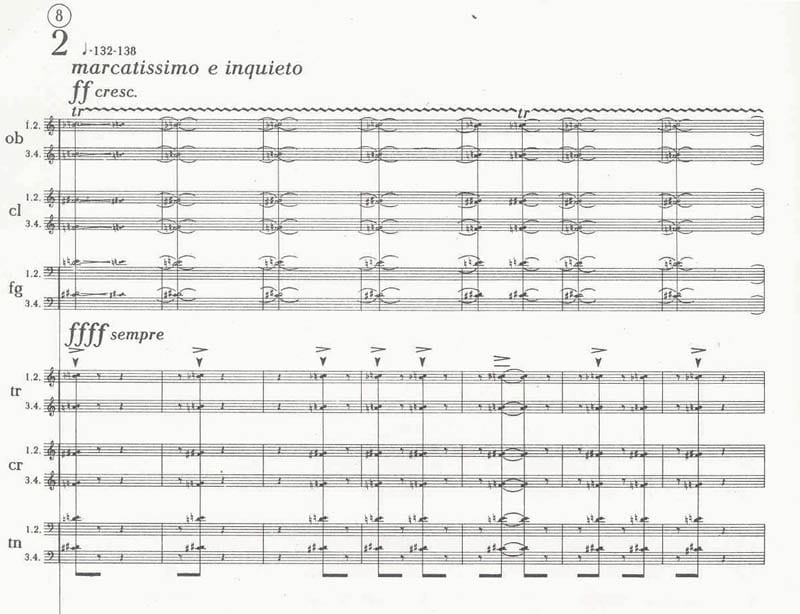

The harmonic structure of the opening section exactly parallels the rhythmic structure. In each refrain, the individual melodic lines move in parallel motion by tones or semitones, and in each new refrain the harmonic content of each chord is extended by the systematic addition of a new whole tone or semitone step to the original tritone (C-F#) of the first refrain. Thus by the sixth refrain all twelve pitches are present, harmonically arranged in two whole-tone scales beginning on C and Db respectively. In this opening section, only strings and brass are used – the former to build the main texture, the latter to provide formal punctuations consisting of just one pitch, F#. Initially (in the first three refrains) the punctuations mark the beginning and end of each palindrome; thereafter they also subdivide palindromes. In these last three refrains, the number of brass attacks increases and becomes less obviously regular, though in refrains four and five they are still palindromic.In contrast to the uniform texture of the first section, the middle section presents a sequence of three distinct textural ideas (A, B, C) in the following order: ABABCBCB. A is based on regular eighth-note patterns in measures of 7/4, separated by measures of 1/4 or 1/8, while C is primarily based on triplet sixteenth-note groups; both A and C consist of palindromes constructed in a number of different ways. B consists of “ad lib., irregular eighth-note repetitions” (that is no exact rhythmic structure) and serves to separate the major palindromic sections.The first rhythmic palindrome in the brass section (Idea A) – accompanied by an unchanging trill in the woodwinds (see Example 2) —is primarily shaped by the number of eighth-note rests separating the eighth note-length chords, though the axis point is emphasized by extending the chord to two eighth-notes (see Table 3).

| chords: | 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 |

| rests: | 4 4 1 1 2 2 1 1 4 4 |

Table 3: Refrain, first rhythmic palindrome in the central section.

The main constituent of A, where strings and woodwinds are in rhythmic unison, is similarly constructed (see Example 3). Here the palindromes are formed by the groups of eighth-notes separated by eighth note rests. The horn and timpani parts also have some symmetrical features but not to the extent of the other instrumental parts. Three basic orderings (5213, 1532, 2135) and their retrogrades are used to form two palindromes (see Table 4). The harmonic content is based on the two alternating chords shown in Example 3, an extreme application of the “utmost economy.” These two palindromes are followed by a section which uses these patterns in the regular sequence shown in Table 5. Even this could, at a broad level, be regarded as a minimal two-element palindrome: 1-2-2-1-2-2-1-2-2-1.

| 1st palindrome (2nd measure of Fig. 9 to Fig. 12): [1532 2135 5213 5312-2135 3125 5312 2351] |

| 2nd palindrome (Figs 12-14): [2135 5213 5312-2135 3125 5312] |

| 2351 3125 3125 2351 3125 3125 2351 3125 3125 2351 |

Idea C (Figures 20 and 22 in the score) comprises two palindromes. The first one is based on two contrasting textures scored for horns; the metrical structure is 3 – 2 – 3 – 2 – 3 measures of 2/4. The individual three-and two-measure sections of this palindrome are also rhythmically and harmonically palindromic. At the smallest level each measure is a rhythmic palindrome. The second palindrome, built on the same principle as the first, is the most complex in the work, presenting both horizontal and vertical symmetry (see Example 4). In addition to the horizontal symmetry of 3+2+3 measures, Górecki’s extension of the texture to include trumpets and trombones creates a harmonic mirror (that is, vertical symmetry) around an F#/G axis in the horn section.

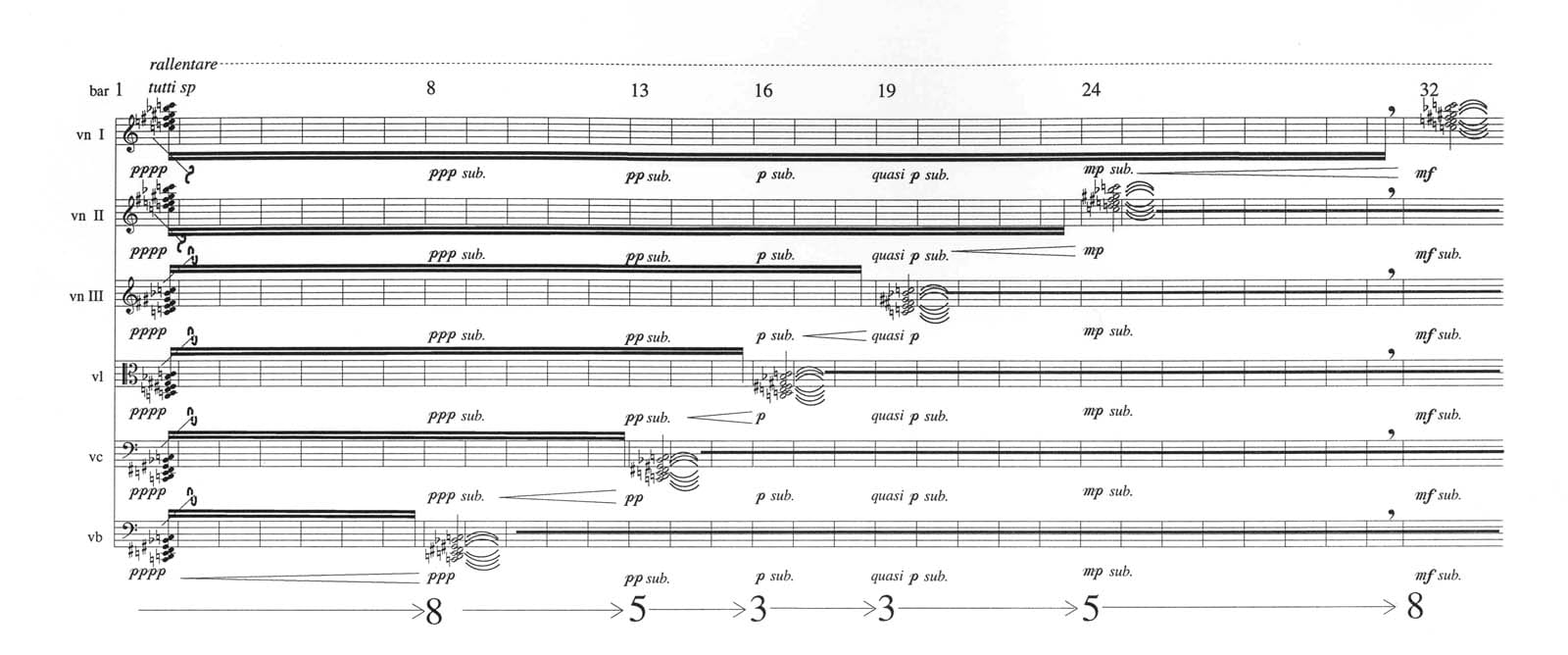

The last section of Refrain is reminiscent of the opening in terms of dynamics and palindromic structures. It comprises four palindromes. The first (see Example 5) is formed by changing the texture of the string parts from tremolo to held chords, going from the lowest to the highest instruments. The number of measures’ delay between the entry of held chords in each instrumental group forms a palindrome: 8 – 5 – 3 – 3 – 5 – 8. The gradual increase in the number of instruments playing static chords is accompanied by a gradual increase in dynamic level from pppp to mezzo forte. The remaining palindromes are formed by the repetition of the 6th “refrain” from the opening, slightly altered and concluding with a three-bar palindrome (refer to Table 2). The reduction of instrumental groups reverses the accumulation of held notes in Example 5.

The palindrome is by no means the only device that contributes to the formal design in Refrain. At the smallest level there are several sections divided by general pauses. The linking of texture and dynamics provides another means of formal division. The dynamic levels are directly linked to the overall three-part form, the outer sections being soft, and the central section loud. Within each major section, however, subsections are also consistently accompanied by a change in dynamic level. For instance, the first five refrains rise gradually frompp to mp, with the sixth refrain sinking back to pp.

Another important factor is textural expansion, a common process in Górecki’s works of this period, which involves gradually increasing the number of parts while simultaneously filling out the pitch range. In Refrain, this proceeds in two dimensions: vertical and horizontal. Although several sections of the piece are essentially static, the textural expansion results in a growing density and intensity of vertical sonorities, while the palindromic sections, which become generally longer and louder each time, also increase in intensity. At the same time, this process gradually undermines the melodic aspect, since the addition of voices makes it less and less possible to hear individual melodic lines. The strict palindromic structures of Refrain begin to loosen in the three major works written between 1967 and 1969: Muzyczka II and two orchestral works, Old Polish Music and Canticum graduum.

Before considering their common structural elements, some comment on their distinctive titles is merited. In some cases the titles are mainly anecdotal in origin; in others, they can provide an insight into the compositional procedures or allude to the original melodic material used in a piece. A trend towards the use of titles without programmatic intention, exemplified by Refrain and Canticum graduum, was a general feature of new music in the 1960s, especially of “new” Polish music; other examples include Górecki’s Scontri and Choros, Boleslaw Szabelski’s Aphorisms and Kilar’s Dipthongos. In such works the title provides the key to the basic sonic concept, formal design, or compositional procedures in the work.[8] In Refrain the title refers to the multiple statements of a single idea. Canticum graduum refers to both the pitch construction, based on whole-tone scales, and its coda which relates to “one of the Polish chants for the prefacja’ Mass.”[9] The title Old Polish Music, on the other hand, does not imply any compositional procedure: it merely indicates a connection with certain original old Polish compositions on which the two major ideas of the piece are based: a fourteen-century organum Benedicamus Domino (see Example 6a) and a sixteenth-century lullaby Already it is dusk (see example 6b),[10] taken from a Renaissance setting by Wacław of Szamotuły (1556).[11]

Muzyczka II is part of a cycle of four pieces. The title uses the diminutive form and is one of the few titles which the composer has discussed:[12]

It all began with conversations among musicians belonging to the same circle. Someone remarked that every new piece nowadays wants to strike “the big bell.” So it seems as if there are no longer any ordinary musical statements that “enlarge” so to speak, the character, features, and mood of everyday life. Acceptance of these everyday and musical happenings does not in any way represent a flight from “big themes,” but is – at least for me – an attempt to rehabilitate those “minor problems” which at a certain moment or in a specific situation may turn out to be, for the composer, the most important problems.

The simple, restricted material of Muzyczka II and many later works, can be regarded as just such an “ordinary musical statement,” another instance of “utmost economy.” The “minor problem” of working with such restricted material was to become a central feature of Górecki’s oeuvre.

The elements of symmetry and contrast described above are decisive factors in shaping the two forms most typical of Górecki’s music in the late sixties: a symmetrical arch form and a linear cumulative-type form. Refrain and Old Polish Music represent an arch-type form; Canticum graduum and Muzyczka II fall into the latter category.

The structure of Old Polish Music is created by alternating three main ideas, each of which is consistently assigned to particular instruments. The fanfare sections, based on Benedicamus Domino, are executed by trumpets and trombones.[13] The second idea, built on the tune Already it is dusk, is assigned to strings. The third brief idea, marked Ad libitum, scored for horns, consists of repetitions of short note values, expanding from groups of two notes to groups of seven. These three ideas are juxtaposed to create a broad structural palindrome in which the central section is based on the Polish lullaby: F T F A F – T – F A F T F (coda), where F is Fanfare, T is Tune, and A is Ad libitum.

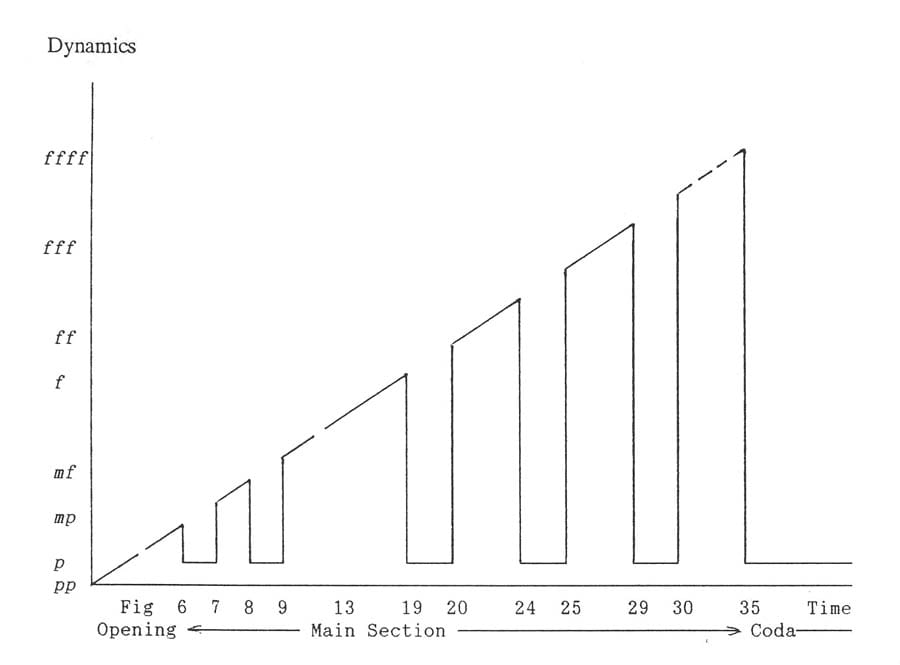

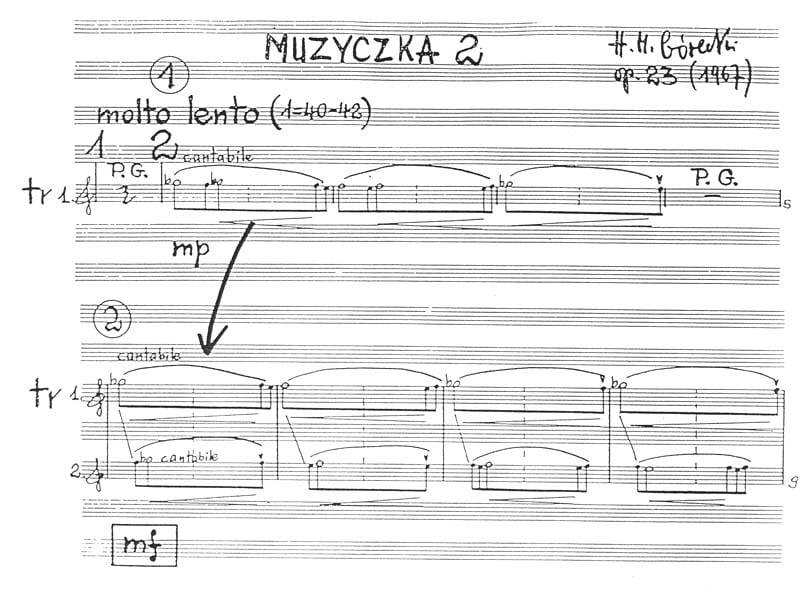

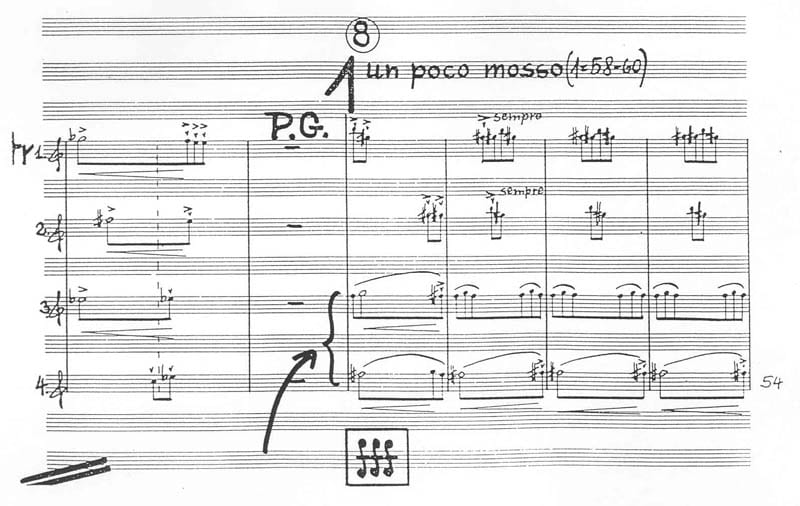

Turning to the “linear” forms, the formal structure of Canticum graduum is essentially a twelve-minute crescendo, interrupted six times by a return to slower piano sections marked dolcissimo, cantabilissimo. The basic shape of the work is represented graphically in Example 7. The form of Muzyczka II is closely related to that of Canticum graduum. The main idea (A), which is expanded and developed throughout the piece from one to seventeen parts, is interrupted three times by idea B for trumpets, trombones and percussion. The main texture of B, which functions in this piece as a brief refrain, consists of trumpet and trombone tremoli, occasionally punctuated by cymbals. The cumulative form is created by the alternation of these two ideas (ABABABA) in conjunction with consistent textural expansion.

In the pieces following Refrain, textural expansion becomes an integral factor in the development of form, and is often linked to the evolution of pitch content. In Canticum graduum, the expansion is linked to the linear crescendo which gives the piece its basic shape. The pitch material, based entirely on whole-tone scales, expands in a very systematic way. Beginning on the note D, the two whole-tone scales alternate and gradually unfold by step in opposite directions. Each time the pitch range is expanded by semitone steps in both directions, both scales gain a new pitch. By the end of the opening section both scales are set against one another to fill out all the pitch classes from A to G-sharp (see Example 8). Similarly, in the middle section the pitch material of the individual melodic lines, which move by step, expands in parallel to the crescendo, eventually involving multiple doubling of all the notes of the two whole-tone scales. At its broadest, the pitch range encompasses four octaves.

In Muzyczka II, the process of adding melodic lines is present at the opening of the piece, which begins with one trumpet part and progresses to four parts (Example 9a and 9b). Additive and repetitive processes play an important role in this piece. For instance, each separate section is extended by the repetition and transformation of motifs. Vertically, the texture expands by the addition of melodic lines which also expand the register. Initially, each addition of new parts follows a general pause. However, this only applies to the opening; throughout the rest of the piece, the introduction of new instruments and new parts is preceded by idea B.One of the ways additional melodic lines are derived is by breaking the initial motif or rhythmic figure into two figures for different instruments, but in such a way that the sum of the two figures gives the original figure (see Example 9a). Another transformation of the original motif is achieved by inserting the retrograde version into the original (see Example 9b).

In Old Polish Music too, the textural expansion proceeds in a very systematic way throughout the whole piece. Each section expands simply by the addition of melodic lines. However, for each of the three main ideas the expansion of texture is based on a different principle. The fanfare section expands by the addition of trumpet–trombone pairs. Two pitches of the melodic lines and grace notes are symmetrical, both through the palindromic numbers of grace notes, and the contrary motion of the grace notes and melody notes. The piano string passages which occasionally interrupt the fanfare section expand by means of additional held notes around a central major third F-A. Only the pitches of a diatonic C major scale are used to fill out the pitch range. As the number of parts increases, so too does the pitch range, reaching a maximum of a major thirteenth.

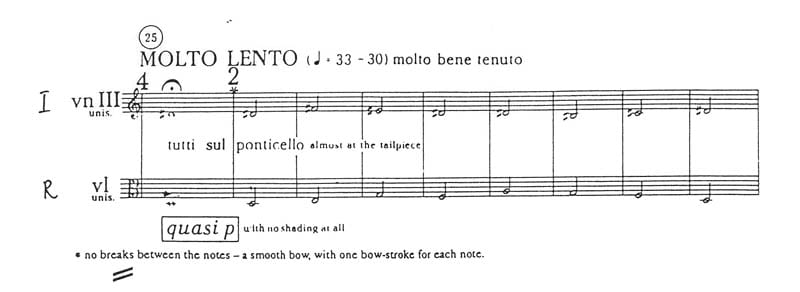

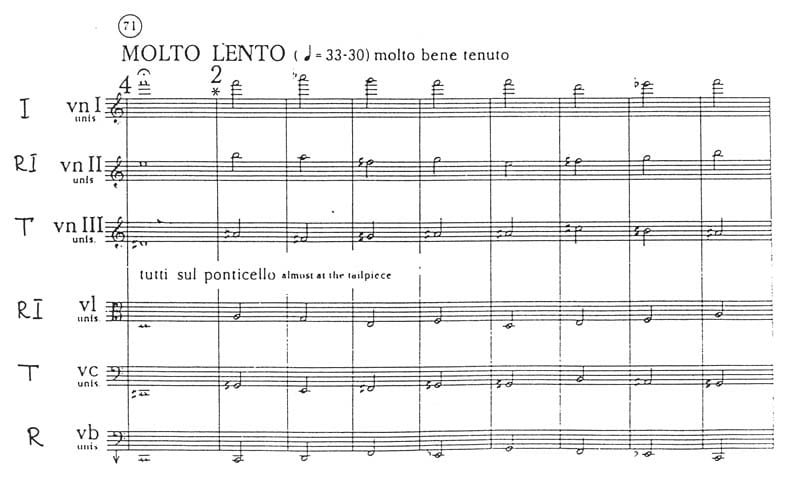

The texture of the section based on the tune Already it is dusk is created by using the tune with three other variants, in accordance with the four forms typical of traditional serial procedures: prime set (the tune), inversion, retrograde, and retrograde inversion (see Table 6). The inversion and the retrograde inversion consistently flatten one note (F) of the original cantus firmus. The vertical build-up in sonority is again achieved through the gradual addition of melodic lines, from two sets to twelve, based on pairing the prime against its most distant complement, the retrograde inversion, and the inversion against the retrograde. The four appearances of this section involve both vertical expansion and lengthening of the section by using more notes of the tune each time. Thus the initial two-part texture which begins at Fig. 25 (see Example 10) uses only sixteen notes of the tune per part (that is, the first and last sixteen notes of the tune), combining inversion with retrograde. The next texture, beginning at Fig. 49, doubles the length of the section by using thirty-two notes of the same tune. In this section the tune appears for the first time in its prime form. The sum of the number of notes of the previous sections (16 + 32) provides the length for the six-part texture beginning at Fig. 71 (see Example 11), using all forty-eight notes of the tune for the first time. The fourth and last statement of this texture, beginning at Fig. 78, reaches a maximum of twelve parts and also uses all forty-eight notes of the tune (without repetition). Here, the lengthening of the section is achieved by changing to an even slower tempo (quarter note = 33-27). The four versions are summarized in Table 6.

| Fig. 25 | Fig. 49 | Fig. 71 | Fig. 78 |

| Vn III: I (D #)

Va: R (D) | Vn II: I (E) Vn III: RI (A #)

Va: P (A) | Vn I: I (F) Vn II: RI (B) Vn III: P (A #)

Va: RI (A) | Vn I: P (C#) Vn I: RI (C) Vn II: P (C) Vn II: R (E) Vn III: P (B) Vn III: R (D#)

Va: I (D#)

|

Notes in parentheses indicate the starting pitch of the “sets.”

| (Fig. 1 – 2): 32123 – 22122 – 32123 |

| (Fig. 3 – 7): 321123 – 2311322111 – 1 – 22331113322 – 321123 |

Numbers designate the number of grace notes in a measure.

Although the palindromes which were the major structural feature of Refrain recur in later works, they lose much of their structural significance. In Old Polish Music only the opening fanfare section is based on palindromes, which are formed by the pithces and rhythm of the grace notes in each measure (see Table 7). To a limited extent, Canticum graduum too is reminiscent of Refrain in that each of the sections marked piano, dolcissimo, cantabilissimo is palindromic in terms of pitch and rhythm. On two occasions, the palindromes in the strings actually extend beyond these piano sections, although it should be noted that they are primarily rhythmic palindromes only (Fig. 19 and 24). Muzyczka II has only two palindromic passages, both in the opening section.

General pauses dividing sections of the piece are one of the most frequent formal devices in Górecki’s works of the mid-to late 1960s. In Refrain, general pauses divide palindromic sections, and separate changes in texture and dynamics. General pauses used for the purpose of punctuation are also prominent at the beginning of Choros I (1964), the work immediately preceding Refrain, but are not integrated into the overall form. These general pauses, which occupy a clearly predetermined and defined place within the structure, are strategically positioned to lend greater dramatic intensity. In later pieces general pauses are still present but not so clearly synchronised with other structural elements. In Canticum graduum they have no particular structural significance, whereas in Muzyczka II, where they appear in the opening sections, they serve an important form-building function. In neither work, however, do they demarcate contrasting textures. In Old Polish Music, general pauses are largely replaced by fermatas.

Górecki’s works in the late 60s were often characterised by “a predetermined model of composition (prekompozycja): a composition based on ‘givens’ presented in the initial section.”[14] The opening section of Refrain not only presents the means of constructing palindromes, but also reveals the material for major sections of the piece. Similarly, in Canticum graduum the basic procedure of unfolding both scales is presented in the opening section. In Old Polish Music, the first appearance of each idea introduces both the basic material and the manner of expanding it. Muzyczka II follows the same procedure of presenting basic strategies in the opening. The three- to four-note melodic figures and manner of expanding are presented in the first measures of the opening section.

In Refrain, all structural features are more or less inseparable, whereas in later works some features attain greater importance than others within the form. In Muzyczka II, dynamics do not play a major structural role, the main form-building element being textural contrast. On the other hand, Canticum graduum, being unified in texture, shifts structural importance to the overall expansion in texture and dynamics. In Old Polish Music the sharp textural and dynamic contrast, makes the previously common general pauses largely unnecessary.

Ad matrem for soprano, mixed chorus and orchestra is the first of two works from 1971 which mark Górecki’s return to vocal music.[15] Although the text provides another dimension to the music, Ad matrem still retains the main characteristics of the instrumental pieces written in the late 1960s. Like the previous instrumental compositions, Ad matrem is a one-movement work which consists of several sections. The means of dividing the sections are the same as in Refrain: general pauses and sharp textural and dynamic contrast.

The overall structure of the work is similar to that of Old Polish Music. Three episodes alternate to create another palindromic structure, while the coda introduces new material: A-B-C-B-C-B-A D (coda). Each of the three sections is based upon a distinctive motive or figure. The opening idea A is constructed by alternating and linking two elements: a very distinct sixteenth-note pulse in the bass drum and timpani, and a tritone figure (Bb and E) assigned to the woodwinds and brass (clarinets, oboes, trumpets and trombones), which is reminiscent of the fanfare figure from Old Polish Music. Idea B (Fig. 13) is in extreme contrast to A in terms of dynamics and texture. The main theme, played mp, is built on a falling fourth (F to C) in the flutes and violins against the background of a sustained minor third in the horns, harp and lower strings. Idea C (Fig. 14) occupies the lower register. The main, chant-like theme centered on D is assigned to violas accompanied by sustained major seconds (Db and Eb) in the cellos, bassoons, contrabassoon and piano. The coda introduces the new material with the entry of the soprano part (see Example 12). Only one line of the Latin text, “Mater mea, Dolorosa, Lacrimosa,” is used, sung over a five-note chord, of which the soprano uses only three notes.[16]

The opening of Ad matrem is typical of the earlier instrumental pieces. Beginning with a single line, new lines are systematically added in parallel with the crescendo. The textural expansion of the coda, particularly in the string accompaniment, links Ad matrem to Old Polish Music. Each group of strings is divided into five parts. The five-note chord lasting throughout the coda is constructed by the gradual addition of new parts in each string group.

The structural use of dynamics ranging from ppppp to ffff (see Example 13) is also typical of Górecki, and is already present in pre-Refrain works such as Choros 1. Whereas Górecki’s general tendency had been to write a crescendo line beginning at the lowest dynamic level of the piece and ending at the climax of the piece, in Ad matrem the full dynamic range fromppppp to ffff is already displayed in the opening section.

The sharp textural contrast is reinforced by changes of articulation and expression marks. Very specific verbal score indications are not common in Górecki’s pieces of this period, but are also not entirely new. Canticum graduum is another work in which detailed indications appear: sempre legatissimo, ben tenuto, molto cantabile, con massima espressione e grande tensione. In Ad matrem they are not only more extreme but, also, unlike Canticum graduum, serve to emphasize contrast. The opening of the piece is marked ritmico-marcatissimo-energico-furioso con massima passione e grande tensione. In contrast, idea B is marked: tranquillissimo-cantabilissimo-dolcissimo-affettuoso e ben tenuto e legatissimo.

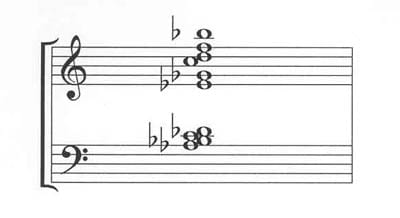

Comparable extremes are also found in Ad matrem‘s harmonic language. Tritones and seconds dominate the A and C sections, while the three B sections are, for the first time since Three Pieces of 1963, diatonic, entirely built on a dominant thirteenth on Ab (see Example 14).[17] Each repetition unfolds more notes of the chord. The second repetition is the longest, the most elaborate, and is placed in the center of the piece (if one excludes the coda). Although the chord does not resolve throughout the section, it has very clear tonal implications.

As ever, all structural elements are used with “utmost economy.” The chorus represents an extreme case: it appears only twice, for one measure each time (Figs 12 and 24). Its use has two significant functions: firstly to accentuates the climaxes, and secondly, at the end of both occurrences of idea A, to underline the arch form (A-B-C-B-C-B-A). The unison chorus parts are based on very limited material: rising and falling minor seconds (E-F-E). This is another example of the masterful use of restricted material to maximize expressive effect.

Just as the organum, the fundamental idea of Old Polish Music, is only fully presented at the end, so the central idea of Ad matrem is a vocal style which is hinted at instrumentally, but only fully revealed in the coda. Although the use of the soprano at the end does not overtly change or influence the overall formal design of the piece, it does have an influence on the music of the instrumental B and C sections where lyrical qualities are most noticeable. Detailed expression markings for the orchestra such as cantabilissimo, dolcissimo also anticipate the lamenting mood of the coda.

Though the form of Ad matrem rests on the same features that are present in the instrumental pieces of the preceding years, there is a considerable change in their structural function. Apart from the overall arrangement of sections, palindromes are not present in Ad matrem: textural expansion and sharp textural contrast, supported by the use of general pauses and dynamics, are the main form-building elements. Here however, they are partly overshadowed by the impact of the vocal element, which operates on two levels: as a structural element and as a principal idea of the coda. Although the use of both chorus and solo voice is very limited, it brings new qualities to the music and a major change in the relationship between the structural features and their audible effect. In the earlier pieces the increasingly dense textures progressively obliterate the melodic aspect; Ad matrem is the first piece in which vocal/melodic qualities come to predominate.

It becomes clear that one of the principal structural trends in Górecki’s works written between 1965 and 1971 is a gradual loosening of structural rigor. Although the pieces following Refrain originate from different ideas, they nonetheless, to a greater or lesser degree, share similar structural elements such as textural contrast, dynamics, palindromes and sections divided by general pauses. However, the relationship between these elements becomes flexible rather than fixed. Coming after a long interest in instrumental pieces, Ad matrem is the first work to return to the more expressive combination of voice and text as well as anticipating a return to major-minor scales. Ad matrem concludes the period in which Górecki was preoccupied with an avant-garde interpretation of “the utmost economy of musical material” and points to the new, modally orientated direction he was to pursue in subsequent works such as Amen, the Second and Third Symphonies, and Beatus vir.

Notes

[1]. This article was originally published in Context 14 (Summer 1997): 15-33; it is reprinted by the kind permission of the editorial committee. [Back]

[2]. By 1960 Leon Markiewicz was already writing that “Henryk Górecki, who made his debut only three years ago, today, as a composer, has established an important position.” See Markiewicz, “O zderzeniach, radości i… katastrofizmie,” Ruch Muzyczny, no. 21 (1960): 5. Translated from the Polish by Anna Maslowiec. [Back]

[3].The articles by Adrian Thomas, “The Music of Henryk Mikołaj Górecki: The First Decade,” Contact 27 (1983): 10-20, and “A Pole Apart: The Music of Górecki since 1965,” Contact28 (1984): 20-31, written well after the pieces were composed, reflected a renewed interest in Górecki’s music outside Poland. Thomas’s recent book Górecki (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997) is the first monograph about Górecki’s music from the avant-garde pieces of the fifties to the latest chamber works written in the early nineties. The book includes a complete list of works and a select bibliography. [Back]

[4]. The phrase “utmost economy of musical material” comes from a conversation between the composer and Tedeusz Marek; see Tadeusz Marek and David Drew, “Górecki in Interview (1968) – And Twenty Years After,” Tempo 168 (1989): 25. Górecki used this phrase to describe the principle of the Muzyczka cycle, but, arguably it applies to all of Górecki’s work of this period. [Back]

[5]. “New simplicity” is a movement which emerged in the late seventies, often associated with Górecki and Arvo Pärt whose music, often religious in inspiration, is characterized by simple homophonic rhythms, slow tempi, and diatonic melody and harmony. [Back]

[6]. Krzysztof Droba, “Górecki, Henryk Mikołaj,” entry in Encyklopedia Muzyczna PWM, vol. 3, ed. Elżbieta Dziębowska (Kraków: Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne, 1987): 429. Translation by Anna Maslowiec. [Back]

[7]. It is worth noting that, in his article and book on Górecki, Adrian Thomas uses the word “palindrome” to describe certain horizontal symmetries in Refrain. In the Polish sources, Droba only mentions the use of “symmetries.” In my conversation with the composer (recorded on tape, Dec. 1995), Górecki described these symmetries as “crab constructions” [rak konstrukcyjny]. [Back]

[8]. Leon Markiewicz, “Główne tendencje twórcze w katowickim środowisku kompozytorskim,” Muzyka 2 (1974): 25. [Back]

[9]. Thomas, Górecki, 65. [Back]

[10]. Both examples are included in Thomas, “A Pole Apart,” 26. [Back]

[11]. Górecki first used this lullaby in Chorale in the Form of a Canon (1961). Nineteen years after Old Polish Music he returned to Already it is Dusk in his first string quartet of the same title. See Thomas, Górecki 128. [Back]

[12]. Marek and Drew, “Górecki in Interview,” 25. [Back]

[13]. The relationship between the organum and fanfare section is relatively free. The direct rhythmic and melodic link is found in the fanfares, which derive from the three eighth note figure of the original organum lines. [Back]

[14]. Lidia Rappoport-Gelfand, “Sonorism: Problems of Style and Form in Modern Polish Music,” Journal of Musicological Research 4 (1983): 405. [Back]

[15]. The other is Two Sacred Songs, for baritone solo and piano. [Back]

[16]. Górecki “derived the harmony of the coda (chord C-Db-F-G-Ab) from his knowledge of Podhalean folk music. . . The lower three notes (C-Db-F) also recall the central ‘lyrical fragment’.” Thomas, Górecki, 72, n. 5. [Back]

[17]. This harmonic interpretation is shared by Thomas, Górecki, 71. [Back]

Anna Maslowiec completed her Honours Degree in Musicology in 1995 at the Conservatorium of Music in Sydney, where she is currently enrolled in the Master of Music program. Her research area is the sonoristic movement in Polish music. She has also written for Ruch Muzyczny.