by Hankus Netsky [1]

Abstract

Although it was never the heartland of Jewish dance music, Poland was the birthplace of a large number of skilled and influential klezmorim. In this account of lives of three dance musicians who came from professional Jewish musical families in Poland in the early twentieth century, Netsky’s paper reveals the musical interactions between Jewish and Polish cultures before World War II. Carl Frydman (born near Częstochowa around 1920, died in Boston, 1979), immigrated to the U.S. in 1935. In Poland he “performed Jewish operettas, Hassidic melodies, and Jewish dance tunes of all types,” but this repertoire was foreign to Bostonian Jews of Ukrainian descent. Accordionist-singer Leo Rosner (b. 1918 in Kraków, Poland) came from a family of musicians and survived the war thanks to Schindler. In 1949 he emigrated to Melbourne, Australia and was established in a large Jewish community there, dedicating his life to klezmer traditions. His repertoire included Rumanian and Hungarian tunes which were not popular in Australia; in contrast the Hassidic and Zionist songs remained current. Of interest was also the striking popularity of the tango and fox-trot among the expatriate community who considered “klezmer” melodies as “Russian” in origin. Ben Bazyler, born in Warsaw in 1922, performed on percussion with his uncle’s ensemble of “Kalushiner Klezmorim;” their international repertoire ranged from tangos, through mazurkas to Jewish melodies. Deported to Siberia in 1941, Bazyler lived in Tashkent since 1947, returned to Poland in 1957, and emigrated to the U.S. in 1964 where continued to earn a living as a musician. Netsky pays special attention to the way the Polish origins and adopted homes of these musicians influenced their careers. [Maja Trochimczyk]

Article

In Joseph Green’s popular 1936 Yiddish Film, Yidl Mitn Fidl (Yidl With His Fiddle), we meet a group of itinerant Polish-Jewish klezmorim[2] right out of a Sholem Aleykhem story.[3]We see them ply their trade throughout the Polish countryside, and eventually we follow them to Warsaw. Here one of them decides to give up music altogether, another auditions for — and finds — a prominent place in a theater orchestra, a third becomes an overnight theatrical sensation, and the last one heads (accompanying his daughter, the overnight theatrical sensation) for a comfortable retirement in America. Thus, in an era when Polish Jewry couldn’t have seemed stronger, the klezmer life is all but abandoned, an archaic vestige of a world that is no longer valid.

Luckily, with the aid of an able remnant of its musical progeny, Poland’s version of klezmer music did weather the assimilation of the 1930’s, and, even more miraculously, survived the Holocaust. In this paper I will tell the actual stories of three dance musicians who came from professional Jewish musical families in Poland in the early twentieth century.

Carl Frydman, son of the celebrated badkhan,[4] Yosef Frydman, was born in the small western Polish town of Chmielnik (near the sacred Catholic city of Częstochowa) around 1920. He studied violin and mandolin, and took a serious interest in all aspects of Jewish music at a young age, performing at local celebrations, for Hassidic[5]gatherings, and for the local Jewish theater. Mr. Frydman emigrated with his entire family to Boston in 1935, and soon after that married a Jewish singer from a small town in the Ukraine. Once settled in his new home, he took over the Jewish and Hassidic music trade that had been abandoned by the local wedding musicians. While he was adept at all aspects of the violin repertoire, he never became a truly “modern” player, and, in the eyes of his fellow Bostonians, remained a “klezmer” until his death in 1979.

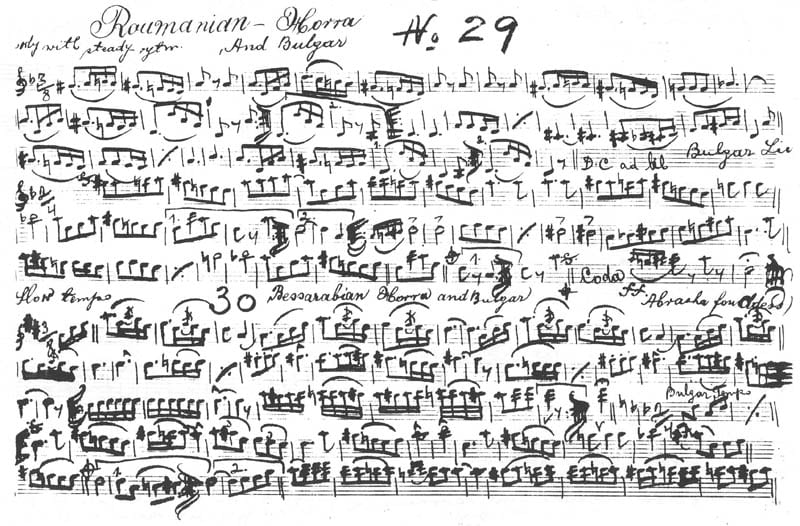

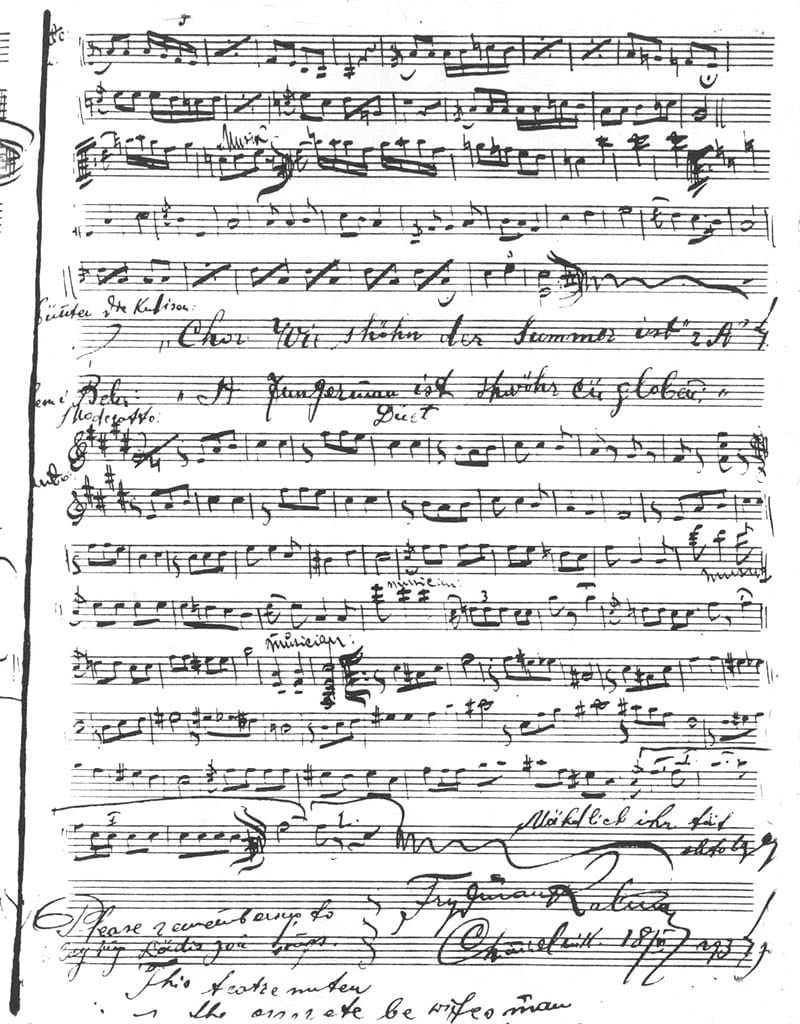

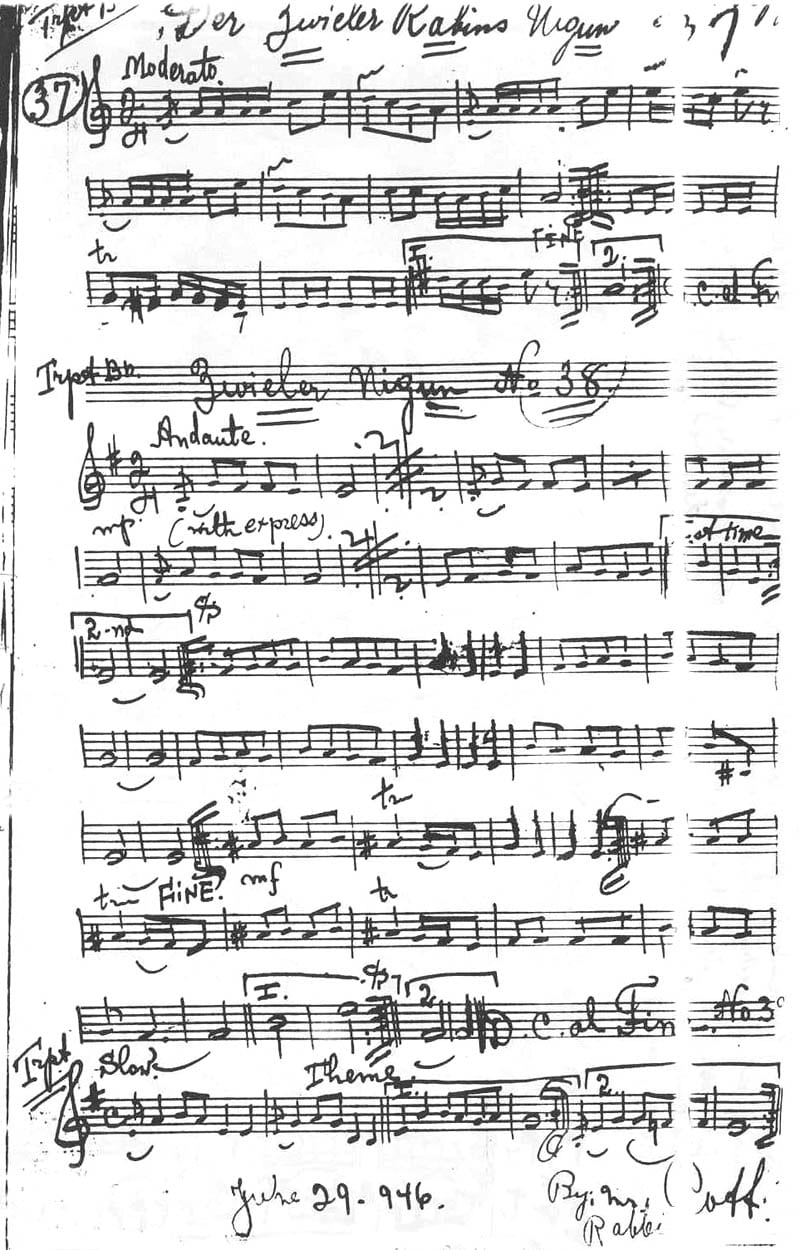

Although I never met Carl Frydman, I have been able to piece together information about his career by talking with other musicians and family members, and by looking at the legacy of musical manuscripts that he left behind. Because Mr. Frydman was meticulous about dating his manuscripts, I was able to ascertain that while in Europe he performed Jewish operettas, Hassidic melodies, and Jewish dance tunes of all types, that he picked up the latest Yiddish theater hits shortly after his arrival in America, and that he continued to add both popular and Jewish music to his repertoire throughout his career.

Paradoxically, even Mr. Frydman’s klezmer repertoire, which he learned in a Polish shtetl, was an anomaly in Boston where Jewish patrons were used to the music of klezmorim from Lazaslav (in the Ukraine).[6] In the absence of a community that shared his origins, he earned a meager living playing and teaching violin, mandolin, and eventually electric guitar, struggling to adapt his repertoire to popular tastes well into the 1970s. His death in 1979 (of cancer when he was in his early sixties) came precisely at the brink of the revival of klezmer and Yiddish music.

I met Carl’s wife Sally shortly after her husband’s death “The Hassidim killed my husband. Stay away from them — they’ll suck your blood,” she said bitterly.[7] Still, her husband had dedicated his life to performing not only for the Bostoner Hassidim, but also for the local Talners, Lubavitchers, and Zhviller’s, whose music he meticulously transcribed as he had been trained to do in small-town Poland. Their melodies remained in his dance folios alongside those of The Beatles and Credence Clearwater Revival, whose tunes subsidized the career of this unheralded and undecorated scholar.

We find both contrasts and similarities in the career of accordionist-singer Leo Rosner. Born in 1918 in Kraków, he picked up music at an early age and soon began performing professionally with his father, self-taught violinist Khayim Rosner, at local Jewish celebrations. At age sixteen he began playing in nightclubs, and learned the popular tangos and fox-trots of his time. Henry, his eldest brother, studied classical violin, and employed several members of his family (eventually including Leo) in his “Kraków Salon Orchestra” beginning in the early 1920s. Leo’s parents and four of his eight brothers and sisters were killed by the Nazis (and their Ukrainian accomplices) shortly after they occupied Kraków. Three of the four Rosner brothers who survived World War II owe their lives to Oscar Schindler who took them in as his “house” musicians (Leo figures prominently in the book Schindler’s Ark, and is the accordionist depicted in the movie, Schindler’s List).[8] In 1949, he emigrated to Melbourne, Australia, and became well established there as a Jewish and society entertainer. His three surviving brothers moved to Western Europe and the U.S. where they worked for many years as popular and classical musicians.[9]

Although eight of the nine Rosner children were musically gifted, only Leo pursued Jewish music as a large part of his career. He credits this fact to his choice of accordion as his instrument, his quick and prodigious ear (at age eighty, he claims a repertoire of fifty-thousand tunes!) and his father’s need for a flexible and mobile accompanist. Clearly his choice of Melbourne as his adopted home also had a great deal to do with his longevity in his field. The community of choice for a large number of Jewish survivors, Melbourne (and Australia in general) is a place where ethnicity is greatly valued. Here George Rosner contrasts his own experience with that of his brother:

Leo devoted his career to playing the Jewish music in Melbourne because he was in a very Jewish place. Here [in the U.S.] I was never [performing] in any Jewish restaurant. I was always in the top places, where they were always anxious as to whether I was Jewish or not. Here in America it’s entirely different. It’s George Rosner, and that’s it![10]

While Leo’s father made a living performing Jewish popular and dance music at weddings, the family shies away from referring to their background as “klezmer.” This may have to do with the loaded image of the klezmer in (especially religious) Jewish society. Here Leo’s older brother, George Rosner, tells the story of his father’s musical origins:

My father was a self-taught violinist. He loved music. He wanted to have a violin, and he couldn’t afford it because the family was poor. The grandfather was annoyed when he was talking about music, “Oh, you are going to be another klezmer?” He was a very religious Jew with a beard. He didn’t want him to have a violin … so he made himself a violin, and the grandfather came and broke it. Then he bought himself a violin and was hiding it somewhere, with a friend or something, and he was just learning by himself, completely self-taught. Soon he was playing a lot of Jewish music, because he was playing yiddishe khasenes (Jewish weddings). I was soon playing with him, as was my brother Henry.[11]

The Jewish wedding repertoire of the Rosner family band consisted mostly of Rumanian (Bessarabian, Moldavian) and Hungarian music. Since the elder Rosner was self taught, the tunes were never written down. Leo’s early Jewish music background came entirely from his father; in his early years he never had any contact with Jewish musicians outside of Kraków nor did he ever recall seeing any Gypsy bands. According to Leo, the Rumanian and Hungarian tunes of his youth became archaic after the war and were generally outlived by the Hassidic and Zionist repertoire. As an urban cosmopolitan Polish musician, he is careful to relegate his overtly “Jewish” repertoire to Jewish life-cycle celebrations. On the other hand, both Rosner brothers are quick to point out the strong Jewish identification with Tango. Indeed, early Argentinean tango was partially informed by a Jewish aesthetic (coming from immigrants to Buenos Aires in the 1890s), and a large number of the Polish hit makers in the 1920s (Petersburgski, the Gold brothers, Karashinski, Andrzej Włast, to name a few) were of Jewish origin.[12]

I saw Leo’s selectivity in action during a 1992 visit, when I had the privilege of observing his band performing at a “Bundist” dance party.[13] Although the crowd was composed almost entirely of Jewish survivors from Poland, I was struck by the absence of what I thought of as Jewish music at the engagement; his repertoire was almost entirely tangos, with occasional fox-trots thrown in. I asked Mr. Rosner what response he might get if he threw in a bulgarish, Russian sher or freylekhs (all popular older Jewish dances), and he quickly replied that everyone would get up and leave. Such music would have no place among urban Polish Jews at an elegant secular gathering.

Because of his relocation to Melbourne, Leo Rosner, unlike Carl Frydman, has been able to maintain a proud sense of place within his Polish Jewish community throughout his career. He has greeted the resurgence of klezmer (what he sees as the old Rumanian repertoire), Yiddish, and Hassidic music among younger Jews with great enthusiasm and is regarded highly by musicians of all ages. He has become a living monument to the torrid history of Jewish music in Poland during this turbulent century.

The third subject of this paper is percussionist and singer Ben Bazyler. I am grateful to Michael Alpert for providing me with a series of personal interviews which carefully document Mr. Bazyler’s life and career.

Ben Bazyler was born in Warsaw in 1922. Although his father, a tavern owner, discouraged him from becoming a musician, by the age of eight he was performing regularly on the poyk(a portable tenor or small bass drum with attached cymbal) with his uncle Nusn in an ensemble known as the “Kalushiner Klezmorim” [Klezmorim from the town of Kałuszyn]. Mr. Bazyler describes his early repertoire as follows:

We played a whole world of music. First there were the melodies for the “seating of the bride” ritual for the wedding. When the party would get going we’d play the Jewish dance tunes like the freylekhs, sher, and khusidl, and also nigunim, Hassidic tunes. We also played the londres and gasn nigunim, dance tunes and processionals in 6/8 time. Then there were tunes “for the table,” for the guests to listen to and to let the musicians show off and make money: a vulekhl or a doina, some zmires, and Yiddish folk or theater songs. You had Polish dance tunes like krakowiak, oberek, na wesoło, mazur, and polonez, and of course polkas and mazurkas and waltzes. And tangos — Polish tangos were very big in the 30’s. Finally, we played Russian folk songs and popular music, and “continental” music, and American dance music. We even played famous classical pieces, like the waltz from Gounod’s Faust.[14]

After the Nazi invasion of the USSR in 1941, the family was deported by the Soviet government to a series of prisons and labor camps in Siberia and central Asia where his parents and sister soon died of starvation. Mr. Bazyler credits his musical skills with keeping him alive in this period. Released in 1947, he settled in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and became active as a musician and concert promoter. It was here that his klezmer career received a powerful second wind, under the influence of Mishka Schuster, a violinist from Bershad, in the southern Ukraine. Schuster used to say:

[G]ive me the wedding and I’ll tear it to pieces … [He] was so steeped in it all … In Poland with my uncle we repeated things many times, but when I played with Schuster we never repeated anything in the course of a night … I like the Odessa style [of dancing]; it’s got a lot of life in it.[15]

In 1957 he returned to Poland, settling in Łódź with his wife and three children, and in 1964 he brought his family to the U.S., moving from Minneapolis to Los Angeles in 1965. Here he worked as an entertainer and barber until his untimely death by suicide in 1990.

Mr. Bazyler was noteworthy for his tenacity in clinging to his unabashed klezmer roots throughout his life, a fact probably linked to his relatively late departure from his southern Ukrainian/Bessarabian-based adopted klezmer community in Uzbekistan. Even as a restaurant musician in Los Angeles in the 1970s and 1980s (playing the drumset) he never forgot about his poyk, and as interest in his “roots music” grew, he soon re-kindled the persona of “Boris Musikant,” the proudly flamboyant klezmer.[16] He generously shared his stories and repertoire with klezmer revivalists, performing regularly with the Ellis Island band, and making guest appearances with Brave Old World.

The lives of Carl Frydman, Leo Rosner, and Ben Bazyler provide realistic scenarios that flesh out the eerily unfinished story of the fictional klezmer band that I mentioned earlier. Their stories speak volumes about the preservation of a musical heritage, cultural continuity, and basic human dignity in the post-Holocaust Polish-Jewish Diaspora. Most importantly, their musical legacies live on, and hopefully will continue to inform and inspire future generations for many years to come.

Notes

[1]. Hankus Netsky is the founder and director of the Klezmer Conservatory Band with numerous LP and CD recordings to his credit. His knowledge of the klezmorim repertoire is that of a practicing musician, as well as a scholar and this paper is based on his personal encounters with the klezmorim discussed here. [Back]

[2]. klezmorim (from the Hebrew, kle zemer = “vessels of song”) is the plural form of klezmer, the Yiddish word for a professional folk instrumentalist. See Yidl Mitn Fidl, directed by Joseph Green (Warsaw: Green Films, 1936). [Back]

[3]. Sholem Aleykhem was the pen name of Israel Rabinovitch (1859-1916), the most renowned of all the Jewish folk authors. One of his most popular characters, Stempenyu, epitomized the popular conception of the klezmer. “His father played the bass … he danced like a bear … (he) comes from ten generations of klezmorim and he’s not ashamed of it. He just grabbed the fiddle and made one pass with the bow, no more, and the fiddle began to speak … with a voice, like (forgive the comparison) a living person, speaking, discussing, singing weepingly in the Jewish manner…” Quoted in Mark Slobin, Tenement Songs: The Popular Music of Jewish Immigrants (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1982), 17. Klezmorim were commonly thought to be “outside the pale of regular community life,” and often found themselves stereotyped not only as mysterious mythic musicians but also as womanizers, drunkards, gamblers, and vagabonds. [Back]

[4]. A badkhan is a Jewish folk poet. [Back]

[5]. The Hassidim were the followers of a mystical strain of Judaism beginning in the 1750s. [Back]

[6]. Albert Drutin, Interview with Carl Frydman, 1997. [Back]

[7]. Sally Frydman, Interview, 1980. [Back]

[8]. The fourth brother, George, found his way to the U.S. just before the war with a traveling popular music ensemble. Already well established as a “tango” composer in Poland, he achieved great success here as a solo pianist with a large international repertoire. Several of his melodies are still popular standards. [Back]

[9]. Interview with Leo Rosner, 1998. [Back]

[10]. Interview with George Rosner, 1999. [Back]

[11]. Interview with George Rosner, May, 1999. [Back]

[12]. George Rosner has composed many popular tangos which he feels have a Jewish signature on them. He sees this as a haunting quality, a tendency of the melody to ask “Why?” This is consistent with how many musicians characterize the Jewish versions of other types of essentially non-Jewish music. [Back]

[13]. The “Bundists” were those Polish Jews who believed that the best hope of their people would be to establish autonomous Jewish institutions within the secular society (as contrasted with Zionists who sought a homeland in Israel). A relatively large proportion of surviving Polish Jewish Bundists emigrated to Melbourne, Australia after World War II. [Back]

[14]. Michael Alpert, All My Life, A Musician (unpublished ms., 1990). [Back]

[15]. Alpert, 1990. [Back]

[16]. Stuart Brotman, Interview with Ben Bazyler, 1998. [Back]

Bibliography

- Alpert, Michael. All My Life, A Musician. Unpublished manuscript, 1990.

- Brotman, Stuart. Interview, 1998.

- Drutin, Albert. Interview, 1997.

- Feldman, Walter Z. “Bulgareascal Bulgarishl Bulgar: The Transformation of a Klezmer Dance Genre.” Ethnomusicology 30(1): 1-35, 1994

- Frydman, Sally. Interview, 1980.

- Goldin, Max. On Musical Connections Between Jews and the Neighboring Peoples of Eastern Europe (translated and edited by Robert A Rothstein). Amherst: International Area Studies Program, University of Massachusetts, 1989.

- Goldman, Eric A. Visions, Images and Dreams: Yiddish Film Past and Present. UMI Research Press, 1983.

- Green Joseph. Yidl Mitn Fidl. Green Films, Warsaw. 1936

- Hoberman, J. Bridge Of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds. New York: The Museum Of Modern Art, 1991.

- Idelsohn, A. Z. Jewish Music. New York: Dover Press, 1993 (originally published in 1929).

- Netsky, Hankus. Yidl Mitn Fidl And The Demise Of The Klezmer. Unpublished manuscript, 1997.

- Rosner, George. Interview, 1999.

- Rosner, Leo. Interview, 1998.

- Sandrow, Nahma. Vagabond Stars: A World History of Yiddish Theater. New York: Harper and Row, 1979.

- Sendrey, Alfred. The Music of the Jews in the Diaspora. New York: Thomas Yoseloff Press, 1970.

- Slobin, Mark. Tenement Songs: The Popular Music of Jewish Immigrants. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982.

Dr. Hankus Netsky is an instructor of jazz, Jewish music, and contemporary improvisation at Boston’s New England Conservatory, where he served ten years as chairman of Jazz Studies. He is the founder and director of the Klezmer Conservatory Band and has composed music to a number of popular films, videos, plays, and radio projects. Mr. Netsky has produced numerous Jewish music recordings, and has played a prominent role in Itzhak Perlman’s In The Fiddler’s House project. Netsky published an article “An Overview of Klezmer Music and its Development in the U.S.” in Judaism 47, no.1/185 (winter 1998):5-12. He is working on his Ph.D in Ethnomusicology at Wesleyan University.