edited by Maja Trochimczyk

1913 Piano Concerto No. 2 | 1915 Monographic Concert | 1916 Prayer for Poland

Analytical Notes on Stojowski’s Piano Concerto No. 2

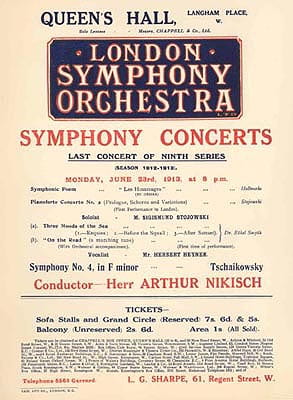

(Program of the London Symphony Orchestra, 1913)

by F. Gilbert Webb [1]

The London Symphony Orchestra:

Twelfth Symphony Concert

Queen’s Hall, London

Monday, June 23rd, 1913 at 8 p.m.

Conductor: Herr Arthur Nikisch

Principal Violin: Mr. W. H. Reed

Soloist: Sigismund Stojowski

Pianoforte Concerto No. 2, Op. 32

(First Performance in London)

Prologue. Andante con moto

Scherzo. Presto ma non troppo

Theme and Variations

Sigismund Stojowski is most widely known to English musicians as the composer of pianoforte music of elegant and effective character, but he has also written, in addition to the concerto played tonight, several orchestral works of important design, including A Symphony in D Minor and an Orchestral Suite. He was born at Strelce, Poland, on May 2nd, 1870, and after studying with L. Zeleuski,[2] at Cracow, went in 1887 to Paris, where he entered the Conservatoire and pursued his training in composition and pianoforte respectively, under Delibes and Dièmer. Subsequently he studied pianoforte playing with Paderewski.

Prologue

As a rule, the term Prologue is applied to introductory matter of importance but small dimension. In this case, however, the section of the concerto so named covers sixty-three pages of the full score and practically takes the place of the usual first movement. It opens Andante con moto with the following theme given out by the Cor Anglais, supported by clarinets and bassoons and muted strings:[3]

It is repeated by the strings, after which the pianoforte enters with an arpeggio which develops into a solo cadenza. At its termination the horns seem to venture on a remark but are quickly silenced by the solo instrument dealing with the principal subject. The strings then comment on this and are answered by the wood-wind, but again the orchestra is silenced by the pianoforte. The woodwind ventures a short phrase after which there comes a pause, and then the strings muted murmur tentatively the chord of A-flat as though in expectation of the pianoforte announcement of [the following theme]:

From this and Example 1 is developed the remaining portion of the Prologue, the writing of which testifies to the composer’s resource, imagination and contrapuntal skill.

Scherzo

No break is made between this and the preceding number, but the rhythm changes from duple to triple measure, and after a few introductory notes from the horns the violas mutter Presto ma non troppo the principal subject:

What may be described as a shout from the orchestra immediately follows, and after some chords from the woodwind the pianoforte takes up the subject, the orchestra faithfully following. The utmost vivacity prevails, and the music grows more chromatic as it proceeds. Ultimately the pianoforte gives out marcato (see Example 4) with the result that for some pages the score contains almost as many accidentals as notes. Presently a return is made to the chief subject, what may be termed varied recapitulation follows, and the section ends with a remarkable series of shakes, the bassoon having the last word, hurrying down the scale with the principal subject.

Finale

At the end of the preceding section the composer has written attacca tema, and this the strings do forte with the pianoforte playing fortissimo, a counterpoint in chords which becomes of considerable importance (see Ex. 4 below). ////5

- No. 1.—Moto sostenuto. In this the theme is played by the Cor Anglais, the viola and cello contunuing a pulsating accompaniment.

- No. II.—This is headed Con espressione poco rubato, and chiefly concerns the pianoforte.

- No. III.—Here the composer writes piu mosso, and indulges in a chromatic counterpoint on the theme which is distributed between the piano and orchestral instruments.

- No. IV.—Allegretto. The measure now changes to 6/8,[4] and the orchestra and woodwind carry on an animated dialogue until the pianoforte enters and seems to protest against the apparent acrimonious retorts between the orchestral instruments.

- No. V.—This is a molto vivace in which the greatest animation prevails between the solo instrument and the orchestra. It leads into—

- No. VI.—Con fuoco agitato. The heading applies chiefly to the pianoforte, the other instruments showing more control.

- No. VII.—Headed con moto energico the theme is submitted to what may be termed despotic government. Octave passages prevail, and the contention between the pianoforte and orchestra suggests the old problem of what will occur when an irresistible force meets and immovable mass.

- No. VIII.—As will be surmised after such an energetic outburst tranquillity becomes a necessity. The strings are muted, the composer has written Andante sostenuto, and when the pianoforte enters it is in a repentant mood.

- No. IX.—Andantino ben moderato. In this the pianoforte is supreme master of the situation. For thirteen bars it is quite alone, when it is joined by the bassoon, subsequently by the flute, and tentatively by the strings.

- No. X.—Allegro molto. The bassoons and strings commence this movement with a version of the theme in 6/8 measure which imparts to it somewhat the character of an Old English dance. The orchestral instruments continue for some time before the entrance of the pianoforte with chords and arpeggi which add brilliancy to the ensemble. This brilliancy increases until after an upward scale passage on the pianoforte and a rush into the key of A-flat, the composer begins to work up a climax which arrives in a section marked poco maestoso. There is a short cadenza for the pianoforte headed Andante con moto containing reminiscences of the thematic material of the Prologue, notably where the pianoforte giving out Ex. 2, while the strings play Ex. 1. In this spirit of meditation on the past the work ends.

Concert of Compositions by Sigismond Stojowski

Programme Notes

Carnegie Hall, March 1st, 1915 [5]

I.

The Symphony in D Minor—Mr. Stojowski’s first—has been written in 1900 and won the prize at a competition founded by Mr. Paderewski for Polish composers and judged in Leipzig. The first performance was given that same year at the opening concert of the Warsaw Philharmonic, Mr. Emil Młynarski conducting. Performances followed at the “Concerts Colonne,” Paris; the Gewandhaus, Lepizig, and in various European cities. The work has been published by C.F. Peters, Leipzig.

In spite of his leaning toward the national idiom, of which he has made ample use in his minor works, the composer of this symphony, in attempting the largest form of instrumental music, evolved along traditional lines and most universal in its appeal, has refrained from what might be termed “genre-music.” Barely the theme of the last movement with its proud, chivalrous character, especially when accompanied by some characteristic rhythmical figures in the bass, carries a suggestion of Poland. The work, voluntarily sober in harmony and instrumentation, maintains in formal structure the main lines of the classical symphony. Nor did the composer choose to deprive himself of that source of riches and variety which came to the classical symphony from the use of different themes for the different movements. But if every movement possesses its own themes, a sort of unity is attempted by the recurrence of some of these, more or less modified, but always recognizable, in the various movements. So, for instance, the theme of the finale is first announced in the slow movement, where it breaks in twice upon the tender mood by a dramatic appeal from the horns. In the scherzo, again, the main theme of the first movement suddenly emerges, in a subdued and altered form, from the bubble of the swiftly moving runs, shakes and tremolos. This whole movement id dipped in a phantastic atmosphere which suggests hustling and dancing elfs in a moonlit night. It has been described by foreign critics as an effective bit of orchestral writing and has often been played separately, namely by Mr. Arthur Nikisch. There is no programmatic pretense to this symphony, to which, however, Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” might serve as a motto. In the opening bars a bass-clarinet, like some enigmatic personage, voices the second subject in a sort of reflective mood, and the whole movement, with its sombre and violent main theme and its alternatives of light and shade, seems to depict the struggle between the “to be or not to be”—until the final assertion of the triumph of light.

II.

The Cello Concerto (Op. 31) is being performed for the first time, and will serve Mr. Willem Willeke, the popular cellist of teh Kneisel Qartette, in what also is his “début” with orchestra in New York. It is in one movement with three main themes and four sections, between which the motive in diminished fifths heard at the outset, serves as a connecting link. A novel formal feature is that the slow movement—andante sostenuto—is interpolated into the development of the first section, which is resumed after that episode, bringing back the second subject and leading on to a finale built upon the rhythmically transformed first theme. The finale is in condensed sonata form, the theme of the andante being used as a second subject and sounded emphaticallyl by all cellos and horns before the close against briskly moving triplets in the upper strings.

III.

The Second Piano Concerto (A-flat Major, Op. 32) has been written at the suggestion of Mr. Paderewski, who has recently included it in his repertoire.[6] The first performance, with the composer at the piano, happened in the twelfth subscription concert of the London Symphony Orchestra (June, 1913) at Queen’s Hall. Mr. Arthur Nikisch was the conductor.

The title of “Prologue, Scherzo and Variations,” under which the work appeared (at Heugel & Co., Paris) indicates that a radical departure has been made from the usual pattern of the concerto. Some of the variations are written for the orchestra alone, and it also is the first and only piano concerto which ends in a whisper. here, again, the themes are several, but interwoven in the various sections which are played without interruption. The initial motive heard in the English horn appears in all the parts; the first cadenza of the pianoforte brings the first bars of what is going to be the theme of the variations, and the latter present the particularity of being evolved out of two themes, one of the two belonging to the “Prologue.” This brings about the juxtaposition of two distant contrasting keys—that of E Minor, in which most of the variations are written, and that of A-flat, in which the work begins and concludes. The last (twelfth) variation, an elaborate finale dealing with both themes, starts in without transition in E Minor after the previous one in A-flat, and after a long drawn climax, which brings back the amplified main theme of the “Prologue,” peace and serenity gradually replace the storm and stress until at the very close the two distant chords are mated together, providing a mysterious ending, suspended, as it were, in the clouds.

Prayer for Poland [Modlitwa za Polskę], Op. 40

A Cantata for Mixed Voices with Soprano and Baritone Solos and Orchestral Accompaniment

Poem by Sigismund Krasinski | English Version by Geo. Harris, Jr.

Bulletin of New Music, Schirmer, New York, 1916[7]

A choral work of sustained power and lofty inspiration, in which the magnificent invocation of the Polish poet, Sigismund Krasinski, to the “Queen of Poland, Queen of the Angels,” the famous Madonna of Czenstochan,[8] admirably Englished by George Harris, Jr., has found a musical setting worthy of its fervor and passionate intensity of appeal. An intruductory instrumental andante con moto is succeeded by an ingenious choral development of th efirst two stanzas of the poem, in a theme of marked nobility, which, in turn, is followed by a short instrumental interlude, after which the suffering of the Divinity for teh sake of her worshippers—”Thorns and cross and driven nails Thou knowest”—is expressed by soprano solo and chorus with a pathos, beautiful in its sincerity and restraint. Another interlude, quasi marcia funèbre, is interposed before the choral close of this stanza. The two succeeding ones are alotted to the baritone solo (in part) and the chorus, and a short allegro feroce, vividly forceful and dramatic, prefaces the stirring music of the lines:

This world is shattered, shattered into pieces!

No single one of its rent and ruptured fragments

Prays any more unto Thee, Oh heavenly Virgin!

“The concluding stanza, beginning, “We only, we now, burning at the scaffold, Forth unto boundless space our prayers are sending,” thrills with a note of deepest and patriotic exhaltation. The Prayer for Poland may be considered, in the choral field, one of the most genuine and beautiful tributes which the arts have paid to patriotism, and one representing the finest effort of both the poet and composer. It will be heard in public for the first time in New York, at the second concert of the Schola Cantorum of that city, under the direction of Kurt Schindler, on March 7th, at Carnegie Hall.[9]

Notes

[1]. This and all subsequent notes by Maja Trochimczyk. Francis Gilbert Webb (b. 1853-?) was a British music critic and musicologist. He published books on Indian music , with Faiz Rahamin (London, Marchant, 1914); Oostersche muziek with Sha Hinda (Amsterdam: Theosofische Uitgeversmaatschappij, 1921). He started as a composer of Granny: Ballad(London: Novello, Ewer & Co., 1884) and The Talisman: Song (London: Novello, Ewer & Co., 1883). For reviews of New York premiere of the concerto of 1915 see the collection of Stojowski reviews in this issue of PMJ. [Back]

[2]. Proper spelling: Strzelce not Strelce; Władysław Żeleński not L. Zeleuski. [Back]

[3]. We modified the spelling of “to-day” but left the term of “pianoforte” as well as all italics in Italian terms, in order to preserve the character of the text. [Back]

[4]. “Measure” refers to “meter.” [Back]

[5]. Insert to the concert program for March 1, 1915 at Carnegie Hall, New York. A full set of reviews from this concert, containing much unacknowledged quotation from the notes and dissenting opinions about the best work on the program may be found in “Reviews of Stojowski’s Music and Concerts” in this issue of PMJ. The reviews are annoted with biographical data about performers. [Back]

[6]. Paderewski played the Stojowski concerto in several concerts, including March 2 and 4, 1916 at Carnegie Hall (with Walter Damrosch conducting), and with the Boston Symphony Orchestra on March 10 and 11 that year, with Karl Muck conducting. [Back]

[7]. The Bulletin of New Music Published and Imported by G. Schirmer is a catalog of Schirmer, issued in February 1916. Other new compositions provided with descriptive introductions are works by A. Buzzi-Peccia, Henry Hadley, Josef Hofmann, Percy Grainger, Max Vogrich, and Horace Nicholl. With the exception of Hofmann (pianist) and Grainger, these composers are almost completely forgotten today. [Back]

[8]. Proper spelling: Zygmunt Krasiński (1812-1859) and Madonna of Częstochowa. [Back]

[9]. For more information about Prayer for Poland see Herter’s article in this issue of PMJ. [Back]