by Zygmunt Stojowski [1]

translated by Marek Żebrowski

An appeal by Życie Muzyczne to proclaim the glory of Maestro Paderewski reaches me at the moment when this very dear name still rings in my ears and my heart, as if carried on wings of vernal inspiration. I have just performed Chopin’s concerto (a work I once studied with Paderewski himself) with the newly formed orchestra in New York City, mindful of the fact that, to some extent, I represent a great tradition that I now pass on to younger generations in turn. Afterwards I had to board a train for Boston, where Dr. Koussevitzky—a great leader of the famous orchestra-followed through on Paderewski’s magnanimous initiative by conducting a rehearsal of compositions submitted for a competition that he had funded himself. The jury (of which I was a member) was asked to select the best entry. As a result of their deliberations under the aegis and thanks to the generosity of our great Master, the ranks of composers are joined today by an unknown youth of twenty-six from Chicago.

And so, Paderewski’s name is coupled with a whole network of connections in the world of arts, various peoples’ lives, their accomplishments and goals. It has been justly said that a great man is thrice great: through his own self, through his deeds and creations and, finally, through the inspiration he gives unto others. And were it held to be true anywhere and anytime, and were it applied to artists or thinkers alike as well as social activists or political leaders, how much more powerful this truth would have become in historically decisive moments like the present, and in relation to a leader that played in it a crucial, even historical a role! In his life, Paderewski opened the gates of immortality by doubling his efforts and accomplishments: firstly by being one of the Titans of Art who carry heavenwards on their own shoulders the torch of culture and, secondly, by being a messenger and inspired spokesman of historical justice and her victorious defender! This is why the coming birthday anniversary, a humanity-enriching occasion, should be for us a doubly festive national holiday!

The 75th birthday celebration indeed is a diamond jubilee of life. The brilliance of that precious stone brings to mind beautiful words Sienkiewicz once uttered about Modrzejewska:[2] “. . there are hearts that seem to be chiseled of diamonds that shall remain unchanged at their inner core”, even in “distant, foreign lands. . .” “Poland is the meaning of my life”, said Paderewski in one of his fiery orations, which set alight the hearts of his compatriots and kept their faith alive at the moment when the dawn of freedom was just about to break the barrier of darkness. Alas, the author of the magnificent Trilogy[3] (a work written “to keep the hopes alive”) and the great dramatic artist (a childhood friend of Paderewski, who was overwhelmed by his splendid talents and who predicted a luminous future for him) did not live to see this momentous historical occasion. How different and surely how much more splendid than any of our most ardent dreams the contemporary reality turned out to be.

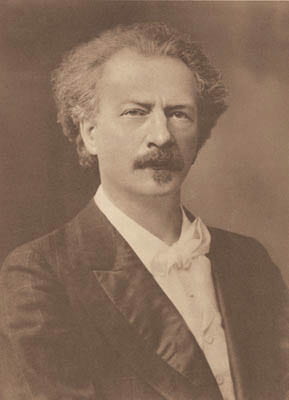

For a mere mortal who reached an advanced age, birthdays are but a family feast, spent in the closest circle of relations, unless one is a loveless loner who prefers to forget matters pertaining to his earthly realm. Unfortunately, there is no warmth of domestic hearth in Paderewski’s life these days, since his beloved companion on this earth has departed into the world of pure light and spirits.[4] Yet, in his loneliness, he is surrounded by universal love. Filled with the restlessly radiant spirit of youth, tireless in his works and thoughts-even if his once golden mane of hair now has a silvery shine and his fair, sunny brow shows deep furrows caused by immutable laws of nature-he has not really aged, just like the ever-young Apollo who blazes a trail of light, illuminating the heavenly firmament with a resplendent track of his mighty chariot. The great American journalist who brought with her my letter of introduction and just paid him a visit in Morges, reported that she found him fresh, youthful, full of life and charm, and that she had partaken there in a real feast of jollity and… wisdom.

Just as this lady now described him, so I remember him from my youth. I, too, have partaken in many of these feasts of “jollity and wisdom” during our long friendship, spanning more than half a century. Being around Paderewski was always-for the young and old-what the English describe as “liberal education.” No amount of stretched hide would suffice to record all his witticisms! I remember how the entire city of Kraków rolled in laughter when, at the wedding of Józef Adamowski in a town called Mogiła, Paderewski in his speech quipped that, unlike most young couples, these newlyweds will reverse their course of life by going “from Grave to Cradle.”[5] I was a young boy, when this red-haired youth, already famous for his extraordinary individuality, charm and fiery temperament appeared upon the small but lovely horizons of a sleepy yet distinguished town, located under the Wawel Castle.[6] My mother, a music lover, was very proud of our new grand piano that had just arrived from Vienna. Our chief music critic warned her that “should Paderewski come calling you at home, you should rather tell him that your piano is locked and you lost the key.” My mother did not follow the advice of this “lightweight” critic and so I met the one with a “lightning touch” at the piano, the very instrument I used to show off myself. “I am very pleased to meet a great artist” were the words, not mine to him but his remark about me, words that he delivered with a smile upon his lips and an extended hand. Since children have unerring instincts about adults, I understood at once something that was later confirmed by life’s experience, namely that—the irony notwithstanding—the extended hand and a friendly smile were gestures of a heartfelt and generous human being. I also found out that for Paderewski the “music and friendship are two different matters.” When I played for him a childish song, he described it “Schubertian” and I was far too stupid to see it as a compliment. Yet the youthful Master was just as direct with a serious and established composer, who was my teacher. After playing his Overture, Żeleński asked with his customary good-natured mien: “Maybe you’ll tell me that this is somewhat like Beethoven?” “No”, was Paderewski’s answer, “because it is Beethoven.” Żeleński was both confounded and, eventually, amused because an honest artist is hurt or angered not by critique, but by human injustice.

Anyway, the young Żeleński was an admirer of Paderewski already. He has heard in his piano playing the same luminous and magical qualities present in the violin artistry of Sarasate, who was famous at the time. He liked Paderewski’s Tatra Album,[7] based on the motifs of Polish Highlands with its “robust” harmony, and the Album de Mai[8] filled with the charm of spring —a work that the influential Leipzig magazine Signale described as “possessing the kind of originality that only a foreign tribe can produce.” As a composer, Paderewski simultaneously struck the national as well as personal chord. Whenever an artistic individuality begins to shine, the reservations of conservative critics surface, as usual. The richly inventive and formally fascinating Variations in A minor[9] produced reaction of heads nodding in disbelief, and I also remember a violinist from Kraków, who tried to defend the unusual harmonization of the Violin Sonata’s main subject as “Spanish” since the work was thought to have come from under Sarasate’s pen…[10]

A few years later in Paris, during a soirée given by my mother in Paderewski’s honour, he and I gave a four-hand performance of Tatra Album. Present among the guests from the French musical world were Charles Marie Widor and Leo Delibes, my composition teacher at the Paris Conservatory. At that time, Delibes was writing Kasia, an opera based on Polish folklore. Paderewski gave him a few folk themes. “What treasures you’ve given me!” the French composer happily exclaimed. A few days later he said to me: “I am in trouble. Paderewski wants me to change everything, according to the way his most original nature dictates everything to him!”

“A mon cher, grand et noble Paderewski,”[11] was the dedication inscribed on the photograph Gounod gave to him, and Paderewski, sure of himself and mindful of the noble ideals ahead, quickly achieved fame, mesmerizing people around him with his charm and disarming them with his sincerity. “Il a le sourire”[12] said the enraptured French, and shortly the Parisian adoration of a man and an artist was transported to London as well. English composers like Mackenzie and Cowen tried to have their works performed by him; they happily accepted his suggestions and dutifully revised their compositions only to be bestowed the honour of his performance… I remember my conversation with Nikisch many years later, when Paderewski’s brightly shining star was compared to the legendary figure of Liszt. Apparently, with the passage of time, Liszt was unable to utter the word “no.” Paderewski, in turn, said Nikisch “may eventually say ‘no’ when it comes to personal affairs, questions of help or support, but in matters of art he can say ‘no’ very firmly.”

Paderewski’s uncompromising artistic judgment was often expressed in a very direct manner, and always in his own, creative fashion. To a young composer’s question, about some high note: “But surely a tenor could reach it?” Paderewski’s answer was: “Especially if he were impaled on a stake.” To a young pianist’s rather impersonal interpretation of Schumann, he said: “. . .but it is a conversation of two souls that understand each other, not yours, young lady, with your gardener!” Paderewski’s inspired artistic concepts were often contained in imaginative aphorisms or descriptions that reached the core of the matter. After many years of friendship, we were listening to a certain virtuoso, who became famous. His able fingers flittered on the keys like butterflies that fly from flower to flower, yet make no honey. Paderewski whispered to me: “A chemist can make everything, except this very simple thing that is a living cell.”

“I’ve got a steel rapier for you” is what a brother says to his wicked in-law in a Polish folksong… Such rapier, drawn from human lips is capable of not only brilliant verbal fireworks in the air but also of annihilating human pride on earth. In time, Paderewski’s enemies got a good taste of his rapier wit with this rejoinder: “When the tree begins to bear fruit, paupers hurl rocks at it!” Such verbal armor is surely an asset in politics, but in art (and in life!) adhering to his uncompromising ideals was Paderewski’s greatest strength. As a result, this great artist was able to proclaim from the free land of George Washington and clearly see the beloved goal of freedom, bravely marching the slippery road towards it through the fog of dissent and nonsensical suggestions of professional politicians who were somehow bound by some geographical considerations!

I, too, have come to know and love these uncompromising ideals, as well as taste the steel of his “rapier” on my own skin when, after earning my Paris Conservatoire diploma I have become subjected to the more strict and discriminating but less academic discipline. His hand, extended in friendship was an immediate reaction of Paderewski at our first meeting and it remained forever at the core of our personal relationship, just as it continues to be a symbol of his relationship to the world and its people. Strange indeed were our lessons! They took place without a set schedule since Paderewski traveled a lot and I was busy with my university studies and compositions. Nonetheless, my summer vacations would always conclude at Paderewski’s villa in Morges where, in equal measure, I was subjected to unparalleled hospitality and wonderful artistic inspiration. One summer I was summoned from Paris to a Swiss resort of Salins-Moutiers, where Madame Paderewska was taking a cure for a few weeks. When I arrived, I found that there was a room with a piano reserved especially for me, and I was told that I shall have a half-hour lesson every day. As it turned out, we were at the piano often for an entire afternoon. Madame Paderewska, who was always kind and favorably disposed towards me, had nonetheless diplomatically remarked after returning home: “one cannot count on anyone these days.” The explanation flowed right away from Paderewski’s own lips: “But I want now to show him everything I know.” No wonder then, that these lessons were so extensive… The very word “everything” was truly a symbolic representation of the artistic psyche as well as a sign of all future and great things… Although an imperfect human being cannot grasp “everything”, an artist wants and must place “everything” on the altar of his beloved art. Giving of oneself, of one’s entire being, of one’s will and energy is what makes the artist a hero and a torch-bearer of civilization!

“The spirit travels the path of human choice”, wrote Professor Jan Kochanowski in his beautiful and deeply moving treatise Wśród zagadnień naszej doby [Among the issues of our times].[13] But the spirit does not know the man-made boundaries that should not be crossed and the various aspects of human thought—at first glance seemingly unrelated—that coalesce and influence each other, just like musical phrases that combine into a multi-faceted unity of a musical masterpiece…

A famous American economist once said to me: “Paderewski’s political role was one of the biggest curiosities associated with the Great War.” It was a natural curiosity, after all. A dreamer and servant of the highest ideals became a leader, an artist became a politician, and a virtuoso turned prime minister! It was really so, for it was he who knew all persons concerned, he could reconcile them, convince them, and move them. Paderewski dominated and stayed ahead of the crowd and, as one of our distinguished leaders had said about him: “He has his genius, he is above our ranks!” The doors that were closed to many were opened for him. The poetical invocation “Arise, my deeds!” rang for him all the more strongly, due to his sensitivity and realization of his own strength and responsibility. When it came to play the heart-strings and make strangers respond with compassion, understanding and justice, as well as touch hearts of his compatriots so that they would beat in unison and harmony for a just cause, he played them as only he would and could!

And so, Paderewski had shown me the art of “connecting phrases” into a spirit of unity of the kind unknown to all experts of sport records, of the kind of varying the sound in such a way that the instrument would sing its soul out, and of the kind that distributes light and shadow in ways that capture our attention and our heart—all of it taking place under a watchful eye of careful and detailed analysis. This is when I found out how deeply conscious and carefully thought-out is his art, so subtle in its sensibility and so direct in its final effect.

That’s why, many years later, I wasn’t surprised by the encounter that took place in New York after one of his concerts. Amy Fay,[14] a pupil of Liszt and author of a well-known book about him, grabbed the Master after a lengthy ovation: “How wonderfully you’ve played today, and how very differently. . .” “How so?” Paderewski interrupted impatiently. “Because you are not a machine”, said the careless woman, trying to save the situation. “Exactly because I am not a machine” Paderewski said, “I always play the same way, since I always do just what I intended to do.”

Just like the changes in a state of inspiration, various stages of artistic development highlight different strengths of the same artist. But in the synthesis of emotions and intellect, called Art, the criteria of the thinking process direct the act of will. Such criteria must be drawn from the nourishment of tradition before an individual and unique talent-grown in such circumstances-may become the life’s nourishment in turn. That Paderewski’s criteria, naturally selective and bred on tradition, do not recognize narrow horizons or doctrinaire thinking, is proven by his relationship to the so-called “modernity”, or at least that part of it that pushed music into new territories over the past quarter century. “There is something to this man”, Paderewski said to me some thirty years ago, when playing through Debussy’s works that were at the time subjected to praise, disagreement and disdain. A little later he added, enthusiastically, “How well this man knows the piano!” I also remember how, years later still, we were listening together to a string quartet by Schoenberg. After the performance, Paderewski turned to the first violinist, who apparently believed in merits of this “masterpiece.” “You are mistaken in your belief, sir, but this work nonetheless contains many interesting details and, at times, even hints at the loftiest of inspirations.” With great joy and due recognition Paderewski welcomed Szymanowski’s great talent. With sincere interest he once listened to the fascinating Chromaticon of Józef Hoffman and to Schelling’s Violin Concerto, whose beautiful Nocturne in Ragusa (just like Szymanowski’s Etude and my Chant d’amour) he had added to his concert repertoire.[15] The solid border between music and friendship stood firm even when Paderewski said to me that he would love to play a new piano concerto, and would be pleased if I were able to write it. Sketches of my work submitted to him in Switzerland were subjected to the merciless critique that I already had experienced before. Since by that time I had resided on the other side of the Atlantic, a lot of time went by before the moment of the world premiere with Paderewski at the piano and the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Dr. Muck, who said on this most memorable for me of evenings that it was “a good service to the arts and a beautiful performance of a new work,” referring to my Prologue, Scherzo and Variations for piano and orchestra.[16]

“It is difficult to create a perfect work,” Paderewski said once, simply adding: “Even when I write, applying my most critical judgment, I cannot succeed either!” Naturally, he can say so, but we should think otherwise. We could only deplore the fact that his life—first the virtuoso career, then the extraordinary turn of history—had kept him away from artistic activity far too often and for far too long periods of time. Madame Trélat, the great French singer to whom Paderewski dedicated his Twelve Songs to words by Catulle Mendčs, [17] had beautifully expressed the feeling shared by all who understood Paderewski’s situation: “But he owes the world the whole of music that resides within him.” I was a guest in Morges just when these songs were being written. Almost every day there was a new one. When Paderewski is in his studio-in peace and silence that are all too rare in his life-he works extremely fast, his fabulous invention creating miracles. But the ever-vigilant self-criticism is always on guard, restraining and fault finding, changing and editing. “The man himself changes” Paderewski was fond of saying, and “after a break, the previous day’s work does not please anymore.” This explains why Paderewski’s published works are relatively few but are always very carefully polished. I know that in his great Variations in E-flat minor[18] of the seventy-two variations sketched out only nineteen and the fugue are present, the latter being his third such work of titanic proportions.

That Paderewski’s compositions seem to be somewhat underrated may be due to his fame as virtuoso, which most likely had pushed the composer into his own shadow. It may also be caused by the fact that human nature does not want nor care to recognize too many talents in one person, and by a certain evolution of the musical thought that corresponds to the spirit of the present times. Paderewski’s muse is much too “euphonious,” lamented one young musician—a very characteristic critique in times of cacophony that is so mercilessly prevalent nowadays in music and psyche! For the Polish artistic legacy, still not too great but already carried to the Pantheon by the genius of our immortal Chopin, Paderewski’s artistic legacy is of first importance. Although with the passage of years its content and outer forms continued to change, the basic imprints of a strong individuality have remained. The ever-present sense of architecture grew from strength to strength, and was recognized by ever-wider circles. His artistic facade that charmed all with the eternal smile of youth was thinly veiled by a thoughtful or daydreaming expression from time to time. It will suffice to mention the fragrant Album de Mai, various Polish dances, humoresques (including the famous Menuet[19] ), the Capriccio à la Scarlatti that bursts like the peals of laughter, his witty Burlesque, and brilliant yet lyrical Intermezzo Polacco. Then came the poetry-smitten Legends[20] with their choice harmonies, and the Variations in A major,[21] that were called “miniatures” in Paderewski’s circle, yet bathed in the same light as his own persona.

That artistic facade changed according to the moods—witness his expressive songs written to poetry by Asnyk and Mickiewicz—assuming, with time, ever more gravitas and powers of dramatic expression. The reflection of this process (or the harbinger of transformation of the composer’s style) is his opera, Manru.[22] Its first act is a charming, idyllic set-piece with choral and dance numbers possessing a strongly nationalistic flavor. Along the lines of noble lyricism the second act proceeds with its beautiful lullaby and a love duet. The symphonically developed personal and tribal drama then breaks open with truly primordial force in the third and culminating act. We will not tarnish dear Moniuszko’s sweet reputation nor diminish Żeleński’s earnest efforts when we truthfully admit that Manru is the first Polish opera of the international rank. With its great technical mastery it is destined for the grandest world stages and, with its racial conflict and drama that is most telling, Manru is a masculine Polish counterpart of Carmen, equal to it with its power of inspiration and richness of color.

On the opposite pole one finds the Symphony in B minor,[23] a monumental work, novel in its form yet inspired and based on Polish character and written much later. It is a giant triptych, the last movement of which is a separate symphonic poem, initiated on the 40th anniversary of the uprising.[24] For the first time in [Polish] music literature, the programmatic content appears within the framework of the “pure” symphonic form, and it crowns the entire work with a kind of patriotic apotheosis. One of the great English critics called this symphony a “Threnody for Poland,” where—prophetically—the aspirations for liberation are embodied by the composer quoting from the national anthem, Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła...[25] (Here, once again, the compositional technique reaches the level of modern contemporary art). “Woher hat er das?”—”Where does he get it?”—a German musician had asked after a performance of the work in Boston, deeply impressed by mastery of orchestral writing exhibited by this pianist-composer. The reception in Paris was similar when the Symphony was heard with admiration and enthusiasm at the Conservatoire by a distinguished audience of famous musicians, led by the aged and severe Saint-Saens. The French minister, Hanotaux called Paderewski a “great builder,” due to his creative nature. Given the richness of his color palette, one could also call him a great painter. The art of erecting sweeping structures of noble arches and filling a wide canvass with saturated colors brings to mind the gift of dramatic instinct that is sensitive to waves of emotion spanning over time and to his keen sense of spatial use of materials. Such instinct-just like his boundless imagination and charged temperament-could be a national trait of the son of our Eastern Provinces, where so many historically dramatic events had taken place. Madame Paderewska had likened the Master to the Arabian stallion of the steppes, and I remember the note of sadness when he told me about his worldwide campaign to regain Polish political rights and independence, but could not lay a claim to the lands of his ancestors, since “asking for too much meant risking everything.”

This, therefore, is a kind of national art, in a deeper, more spiritual sense, that functions as a mirror of the psyche and of aspirations, rather than the artificially stylized harvest from one’s own backyard where, according to the simple wisdom of the Cracovian peasant, “whatever’s red is best.” It is because Paderewski is critical of the narrow, nationalistic exclusivity, as in works by Grieg, for example. Nonetheless, some German fellow had complained to me: “It is a Polish Violin Sonata, a Polish Piano Concerto, everything’s too Polish.” The A minor Concerto’s[26] first movement does strike a familiar, yet fresh note that is lightly veiled in melancholy, but it also has classical lines and dimensions. The dreamy central movement—a Slavic romance—has superb sound textures, and the last movement has a sweep of a wild torrent in its rhythmic liveliness. The other work of Paderewski scored for piano and orchestra—the Polish Fantasy—is a soaring composition, filled with inventive, lively and colorful thematic material that is deftly combined with excellent, truly Polish traits.[27]

Just as there is a long pause and a large contrast between his opera and the symphony, so the concerto and the fantasy are quite different from Paderewski’s later piano works. The massive, volcanic Piano Sonata[28] does not exhibit any Polish traits at all. Like a fresco by Michelangelo, it is drawn in bold strokes and glows with a fiery passion that is angry and tragic, even if the sublime Andante, begun in a sunny contemplation, soars in a huge crescendo heavenwards with a hymn that is underpinned by some evil, fateful rhythms in the bass, only to be followed by the mighty Finale that takes off like an avalanche on a motive taken from the first movement… At first, the Sonata seemed modernistic and full of dissonance to the audiences, just like the Variations and Fugue in E-flat Minor—considered (next to the Sonata) Paderewski’s most substantial piano work. These days, the Sonata is criticized for being, “after all” romantic, just as if art was not in itself romantic, or the critics of the so-called “romanticism” did not outgrow its peculiar ills or its alleged “excesses.”…

Art as mere form without content does not have Paderewski’s imprimatur. Nor does the novelty for its own sake or empty, superficial virtuosity… Nonetheless, Paderewski had proven himself to be an innovator, be it in his experiments with form (as in combining a symphony with a symphonic poem or using a fugal forms in the final movement of his Piano Sonata), or his bold and inventive treatment of harmony (as in the beautiful passages in sevenths at the close of Legend No. 1, or the octave shifting of harmonic resolutions and the semitone variation from his last cycle of Piano Variations). The harbinger of the modern usage of the semitone interval was already present in the youthful Barcarolle from Album de Mai, and in the still unpublished Etudes, where parallel seconds, augmented thirds and fourths are flowing forth liberally—a great wealth of new harmonic and pianistic ideas is to be found there… But the most desired novelty is that which is given to art and life by every sincere human being, since the universal truths there are reflected in a new and personal way!

Paderewski himself—a masterpiece of Divine creation—is an embodiment of this novelty! His is a wonderful persona, a kind of amalgamation of usually mutually exclusive gifts, a harmonious liaison of opposing elements like water and fire—a peculiar alchemy indeed that is hard to grasp, yet palpable to each and everyone alike… “Art does not need to be understood, it is enough to feel it,” Paderewski said once said. The goal of Art he had so described: “The Art must soar, not crawl!” Perhaps in his statements we can find the key to a puzzle, a solution to the mysterious charm that this persona and art have on the masses, an explanation of the cult that has had countless faithful over the years and generations? The crowds indeed sense the purity of this art and the moral authority of the man who controls them both. This is why Paderewski’s concerts became a festive ritual. On his mere appearance, even before he begins to play, almost involuntarily and as if moved by some invisible hand, the crowds rise to greet him. Truly unforgettable was the sight of the huge space of Madison Square Garden in New York City two years ago on the occasion of Paderewski’s charity concert.[29] Touched by a wave of bankruptcies, his modest and much poorer brothers in Art had received from Paderewski a truly regal gift, according to his well-known style. Upon his own wish, the huge space—usually given to skating and races on ice—was hired for the performance. Five thousand dollars were spent on removing ice and converting the space into a concert hall. And twenty-five thousand guests were present, who rose as if touched by a divine lightning rod. It was a truly moving occasion.

Is it possible to describe one’s impressions of this miraculous artistry, to express with words its defining characteristics? A lot was said about Paderewski’s playing—he was praised to high heaven, analyzed and criticized, just like everything and everybody. But in this case, the artist may have a slight advantage over the critic. “Aimer c’est comprendre”—”To love is to understand,” and when one wants to understand everything first, there is nor the energy nor time to love… Even before the experts in aesthetics of art talked of “art as expression,” or of music as a “sound within the formal concept,” they were at last able to notice that “expression” or feelings are revealed by details that they inhabit and that the whole is governed by laws of intellectual construction, as well as that both approaches are mutually compatible— which is exactly what Paderewski’s playing constantly underlined as a duality of our kind of art. A great and mighty architectural line spans a multitude of details here, which in turn possess an inventive fantasy, a subtle charm or a heartfelt emotion… From time to time, here and there, we are struck not by some surprising trick but by finesse, perhaps one note or a chord suddenly illuminated with a ray of different light, or some fresh rhythm or accentuation that are underlined in a characteristic fashion. These things are simple yet expressive, matters heretofore not discovered by anyone, just like the Columbus’ egg… Towering above it and controlling it all is a gift of synthesis, respect for the line, style and basic character of the work. Paderewski has been accused of playing according to his own rules, changing the score or rhythm, which is untrue insofar as certain small variations or light but competent “retouching” are dictated by purely musical or harmonic considerations. These are never of the plain virtuoso variety and out of turn like cocktails after dinner. Paderewski feels music more acutely, shapes music more skillfully, and expresses music more strongly than the academically routine performance or a shallow virtuoso stunt. Harmoniousness, the sensual beauty of music, is the foundation here: his tone is mighty, singing, thundering or sweet, rich in unlimited shadings and a poem in itself. The spiritual appearance of this great art is manifested first by crystalline clarity and then by life, pulsating in every single cell indeed… As a result, Chopin’s Ballades, Nocturnes or Mazurkas are like stars that descended from the sky: “The smaller the work, the greater the artist”, as Bronislaw Hubermann once very aptly observed. But a great Beethoven Sonata is “a stream of hot lava, channeled into granite riverbed”, according to a beautiful line of Rolland. And so Liszt-the-virtuoso comes alive with a rainbow of colors as the Master here lets his imagination reign free, completing the colorful sketches of his predecessor and elevating them to something supernatural in his own image. No wonder then, that after a concert there is a huge crowd surging towards the stage, encircling it and endlessly shouting for encores. It is just like the cold-blooded animals, leaving their swamp-bound existence in order to bask in the warmth of brilliant sun…!

Michelangelo had once said: “Sun is the shadow of God.” This is the “shadow” that the human soul desires and the sun that it ardently seeks. Whoever radiates such rays from his hands and face and emits such warmth and light, deserves only love as the answer or a deed of gratitude! In a critical and decisive moment, it is indeed lucky for Poland that a man who has already conquered the hearts of the world and a man able to awaken the conscience of the world could be found. This is the man who gave his artistic talents freely on the altar of sacrifice for his Homeland… And so, just like the thousands that rise in concerts halls worldwide, for the coming anniversary a crowd of millions will rise under the skies of Poland and, extending from all compatriots at home and abroad, carry heavenwards the cry of happiness and gratitude: “May Long He Live and Be Forever Respected like Our Great Nation, Art, Our Homeland and the Kingdom of the Immortal Spirit!

Notes

[1]. Original publication data: Zygmunt Stojowski, “Paderewski w świetle moich wspomnień i wierzeń.” In Wieńczysław, Brzostowski, ed., “Ignacy Jan Paderewski,” special issue of Życie muzyczne i teatralne vol. 2 no. 5/6 (May – June 1935): 5-11. [Back]

[2]. This and all subsequent notes by Marek Żebrowski. Helena Modrzejewska (born Jadwiga H. Misel; 1840-1909). Polish actress, also known as Helena Modjeska. Emigrated to the United States in 1876. Acclaimed for her Shakespearean roles, she appeared in theatres throughout the U.S. and Europe and resided in Southern California. [Back]

[3]. Reference to Henryk Sienkiewicz (1846-1916), Polish writer who received Nobel Prize for Literature in 1905. The “Trilogy” is a cycle of three epic novels about Poland in the 17th century: Ogniem i mieczem [With Fire and Sword], Potop [The Deluge] and Pan Wołodyjowski [Mr. Michael], published in 1884, 1886, and 1888 respectively. [Back]

[4]. Reference to Madame Helena Paderewska (neé Rosen; formerly Helena Górska) who died on 16 January 1934 after a long illness. She was 78. [Back]

[5]. Paderewski’s play on words: the small town’s original name is Mogiła [Grave]. [Back]

[6]. The author of the article uses a historical reference to his native town of Kraków (Cracow). [Back]

[7]. Also known as Album Tatrzanskie, Op. 12, written in 1884. [Back]

[8]. Album de Mai: Scčnes Romantiques pour Piano Op. 10, written in 1884. [Back]

[9]. Variations and Fugue in A minor, op. 11, written between 1882-1884. [Back]

[10]. Sonata for Violin and Piano, op. 13, written in 1880 and dedicated to Pablo de Sarasate. [Back]

[11]. “To dear, grand and noble Paderewski” [Fr.] [Back]

[12]. “He has the smile” [Fr.] [Back]

[13]. “Some issues of our times”, written by Jan Korwin Kochanowski (1869-1949), a mediaeval historian and professor at Warsaw University. [Back]

[14]. Amy Fay (1844-1928) was an American pianist and writer on music. She studied with Tausig, Kullak, and Liszt. After returning to the U.S. in 1875 she lived in Boston, dedicating her career to advancing the cause of women in music, teaching, and conducting. In 1903-1914 president of New York Women’s Philharmonic Society, author of a book Music Study in Germany (1880) with recollections of Liszt. [Back]

[15]. Ernst Schelling (1876-1939), American pianist, composer, and conductor. He was, along with Stojowski one of the earliest students of Paderewski, with whom he studied in 1898-1902. Schelling’s Nocturne of Ragusa and Stojowski’s Chant d’amour were played very frequently in the early 1900s. For a study of Paderewski’s use of Chant d’amour see Maja Trochimczyk, “‘How Paderewski Played:’ Paderewski, Chant d’amour and the Aestheticism of the Gilded Age,” paper read at the 2002 Meeting of the American Musicological Society, Columbus, Ohio, November 2002. [Back]

[16]. Stojowski’s Prelude, Scherzo, Variations for piano and orchestra is the same work as his Piano Concerto no. 2, premiered in London in 1913 and first played in the U.S. in 1915. For more information see Joseph Herter’s “Catalogue” in the present issue of PMJ. See also reprints of the 1915 concert reviews in Maja Trochimczyk, ed., “Stojowski Concert Reviews,” this issue of the PMJ. [Back]

[17]. Paderewski’s Op. 22, written in 1903. For a study of this work see Małgorzata Woźna-Stankiewicz, “Poezja C. Mendèsa w pieśniach Paderewskiego i kompozytorów francuskich” [C. Mendès’s poetry in songs by Paderewski and French composers]. In Warsztat kompozytorski, wykonawstwo i koncepcje polityczne Ignacego Jana Paderewskiego [Composers workshop: Performance and political conceptions of Ignacy Jan Paderewski] [Meeting: Cracow, 1991]. Edited by Andrzej Sitarz and Wojciech Marchwica. Kraków: Musica Iagellonica, 1991. English translation by Maja Trochimczyk, “The Poetry of Mendès in the Songs of Paderewski and French Composers,” Polish Music Journal 4 no. 2 (2001). [Back]

[18]. Variations and Fugue in E-flat minor, Op. 23, written in 1907 and dedicated to William Addlington. [Back]

[19]. A reference to two sets of piano pieces, called Humoresques de Concert pour Piano, Op. 14, written in 1884-1885, dedicated to Annette Essipov and Alexander Michałowski. The first set, A l’Antique includes the famous Menuet, Sarabande and Caprice. The second set, A la Moderne includes Burlesque, Intermezzo Polacco and Cracovienne Fantastique. [Back]

[20]. Nos. 1 and 5 from Miscellanea pour Piano, op. 16, written in 1887. [Back]

[21]. No. 3 from Miscellanea pour Piano, op. 16, written in 1887. [Back]

[22]. Lyric Drama in 3 acts to a libretto by Alfred Nossig, based on Józef Ignacy Kraszewski’s novel, Chata za wsią [A hut beyond the village] 1893-1901. For more information about this opera, including a 1901 American review, English version of the libretto, and articles by Andrzej Piber and Aleksandra Konieczna see PMJ 4 no.2 (winter 2001). [Back]

[23]. Symphony Op. 24, written in 1907 and named “Polonia.” [Back]

[24]. A reference to the January 1863 uprising of Poles against the Tsarist government. [Back]

[25]. Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła… [Poland”s not lost as long as we live…], also known as “Dąbrowski’s Mazurka” was officially declared to be Poland’s national anthem in 1926. The text is by general Wybicki and the music anonymous; the song was created for the Polish legions in the service of Napoleon in 1795. [Back]

[26]. Paderewski’s Op. 17, written in 1888 and dedicated to his teacher, Theodor Leschetitzky. [Back]

[27]. Full title: Polish Fantasia on Original Themes for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 19. Written in 1893 and dedicated to Princesse de Brancovan. See Henry E. Krehbiel’s “Analytical Notes for Paderewski’s Programmes” in Polish Music Journal 4 no. 2 (2001). [Back]

[28]. Piano Sonata in E-flat Minor, Op. 21. Written in 1903 and dedicated to Archduke Charles Stephen of Austria. See Henry E. Krehbiel’s “Analytical Notes for Paderewski Programmes,” in Polish Music Journal 4 no. 2 (2001). [Back]

[29]. A reference to Paderewski’s 1932 concert tour of the United States that ended with a concert in Madison Square Garden for the audience of, according to other sources, sixteen thousand. It raised $37,000 for unemployed American musicians. [Back]