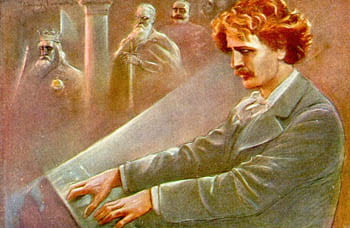

by Ignacy Jan Paderewski [1]

translated by Laurence Alma Tadema

Translator’s Foreword

The following discourse was written in Polish, and delivered in Polish to a Polish audience, at the opening of the Chopin Centenary Festival in Lemberg (Austrian Poland), on Sunday October 23rd, 1910. [2] The author, diffident of presenting to the English-speaking public so essentially national an expression of thought and feeling, at first withheld permission to publish a version that should not previously have been modified and tuned by him for foreign ears. But the translator believes that a faithful rendering of the address, as written and spoken by Mr. Paderewski, cannot fail to be valuable and illuminating to all who – owing to the shadow under which Poland lies temporarily quenched and darkened – are unfamiliar with the spirit of the Polish race; she believes that every lover of music must welcome the light here thrown upon Chopin’s genius.

It is perhaps necessary to add, in explanation of the opening paragraphs, that in July 1910 a great National Festival was held at Cracow to celebrate the famous victory by which Poland on July 15th, 1410 routed, on the field of Grunwald, the Teutonic Knights of the Cross. A monument commemorating the 500th anniversary of the battle was on this occasion presented by Mr. Paderewski to the City of Cracow. [3]

Chopin

We are here to honour the memory of one of Poland’s greatest sons.

Lately, in Cracow, on a luminous and unforgettable day of July, we paid homage to those valiant forefathers by whom our country was up-built; to-day we bring thank-offerings of love and reverence to him by whom it was enriched and marvelously beautified. We do this not only in remembrance of a dear past, not only in justifiable and conscious pride of race, [4] not only because our bosoms are still quick with sparks of that inextinguishable faith which was, and always will be the noblest part of ancestor-worship, but because we are deeply convinced that we shall go forth from these solemnities strengthened in spirit, re-inspired of heart. And we are in sore need of strengthening, of reinspiration.

Blow after blow has fallen upon our stricken race, thunderbolt after thunderbolt; our whole shattered country quivers, not with fear but with dismay. New forms of life which had to come, which were bound to come, have waked among us on a night of dreadful dreams. The same wind that blew to us a handful of healthy grain, has overwhelmed us in a cloud of chaff and siftings; the clear flame kindled by hope of the Universal Justice has reached us fouled by dark and blackening smoke; the light breath of Freedom has been borne towards us on choking, deadly waves of poisoned air.

Our hearts are disarrayed, our minds disordered. We are being taught respect for all that is another’s, contempt for all that is our own. We are bidden to love all men, even fratricides, and yet to hate our own fathers and brothers should they think otherwise, albeit no less warmly, than ourselves. Our new teachers are stripping us of the last shred of racial instinct, yielding the past in prey to an indefinite future, thrusting the heritage of generations into the clutches of that chaotic ogre whose monstrous form may loom at any moment above the abyss of time. The immemorial sanctuary of our race, proof until now against the stoutest foe, is being assailed by brothers who batter at the walls, meaning to use our scattered stones for the building of new structures – as if these poverty-stricken architects were unable to afford material of their own! The white-winged, undefiled, most holy symbol of our nation is being attacked by croaking rooks and ravens; strange, ill-omened birds of night circle around her, screeching; even her own demented eaglets defy her.

“Away with Poland!” they cry, “Long live Humanity!” – as if Humanity could live by the death of nations! In such moments of distraction and turmoil we turn towards the past and wonder anxiously: Is all that Was worth nothing, then, but condemnation and contempt? Are only that which Is, and that which May Be, worthy of regard and faith? The answer is not hard to find.

Here, at this very moment, there rises amid us, above us, the radiant spirit of one who Was. What light, what valour, what energy were in him! – what strength of endeavour he showed in the midst of suffering! Through trouble and affliction, through heart-ache, through creative pain, he marked to his country’s glory the burning trace of his existence. By a bloodless fight fought on the plains of peace, he assured the victory of Polish thought.

Blessed be the past, the great, the sacred past which brought him forth!

A belief has been widely spread that Art is cosmopolitan. This, in common with many other widely-spread beliefs, is mere prejudice. That which is the outcome of man’s pure reason, Science only, knows nothing of national boundaries. Art, even Philosophy, in common with all that springs from the depths of the human soul and is the outcome of an union between reason and emotion, bears the inevitable stamp of race, the hall-mark of nationality. If music be the most accessible of all the Arts, it is not because she is cosmopolitan, but because she is of her very nature cosmic.

Music is the only Art that actually lives. Her elements, vibration, palpitation, are the elements of Life itself. Where Life is she is also, stealthy, inaudible, unrecognised, yet mighty. She is mingled with the flow of rushing waters, with the breath of the wind, with the murmur of forests; she lives in the earth’s seismic heavings, in the mighty motion of the planets, in the hidden conflicts of inflexible atoms; she is in all the lights, in all the colours that dazzle or soothe our eyes; she is in the blood of our arteries, in every pain, passion, or ecstasy that shakes our hearts. She is everywhere, soaring beyond and above the range of human speech unto unearthly spheres of divine emotion.

The energy of the Universe knows no respite, it resounds unceasingly through Time and Space; its manifestation, rhythm, by the law of God keeps order in all worlds, maintains the cosmic harmony. God’s melodies flow on unbroken across starry spaces, along Milky Ways, amid worlds beyond worlds, through spheres human and superhuman, creating that wondrous and eternal unity, the Harmony of Universal Being. Peoples and nations arise, worlds, stars, suns, that they may give forth tone and sound; when silence falls upon them, then Life ceases also. Everything utters music, sings, speaks, yet always in its own voice, using its own gesture, according to its own particular hunger. The soul of a nation, too, speaks, sings, utters music – but how?

Chopin best of all can tell us. Human music is but a fragment of eternal music. Its forms, created by the mind and hand of man, are subject to frequent transformations. Times change, peoples change, thought and feeling take new shapes, put on fresh garments. Sons bow their heads unwillingly to that which moved and enraptured their fathers. Every new generation in its hour of dawn, filled with the dreams of youth, its thirsts, intoxications and enthusiasms, thinks itself called upon to impel humanity towards heights unmeasured, believes itself an appointed path-finder, a thinker of thoughts, a doer of deeds greater than any of those which came before. Every new generation desires beauty, but a beauty all its own. In this spirit are begotten works of art which come to life, as it were, to serve the needs of the moment, and which sometimes endure a shorter space of time than their creators. Others, longer-lived, bear the stamp not merely of one generation, but of a whole period, whose lights and ideas they still reveal after long years. But there are works of yet another order, strong with undying youth, luminous with unchanging truth, in which there speaks the voice of every generation, the voice of a whole race, the voice of the very earth which brought them forth.

No nation in the world has reason to pride itself on greater wealth of mood and sentiment, on emotions more delicately tuned than ours. The hand of God strung the harp of our race with chords tender, mysterious, mighty and compelling. Yearning maidenhood, grave manhood, tragic and sad old age, light-hearted joyful youth: love’s enfolding softness, action’s vigour, valiant and chivalrous strength – all these are ours, swept together by a wave of lyric instinct. Here may be found, perhaps, the secret of a certain enveloping charm that is ours; here, too, may be our greatest demerit. Change follows change in us almost without transition; we pass from blissful rapture to sobbing woe; a single step divides our sublimest ecstasies from the darkest depths of spiritual despondency. We see proof of this in every domain of our national life; we see it in our political experiences, in our internal developments; in our creative work, in our daily troubles, in our social intercourse in all our personal affairs. It is palpable everywhere. Maybe this is only an inherent characteristic; yet when we come to compare ourselves with other happier and more satisfied races, it strikes us rather as being a pathological condition; if this be so, it is one which we might specify, perhaps, as inborn national Arythmia. This Arythmia would serve to explain the instability, the lack of perseverance with which we are generally credited; we might there find the source of our, alas, undeniable incapacity for disciplined collective action; therein, doubtless, lies some of the tragedy of our ill-fated annals.

Not one of those great beings to whom Providence entrusted the revelation of the Polish soul was able to give such strong expression as Chopin gave to this Arythmia. Being poets, they were hampered by limiting precision of thought, by the strictness of words; no language can express everything, not even ours, for all its wealth and beauty. But Chopin was a musician; and music alone, perhaps alone his music, could reveal the fluidity of our feelings, their frequent overflowings towards infinity, their heroic concentrations, their frenzied ecstasies which tightly face the shattering of rocks, their impotent despairs, in which thought darkens and the very desire of action perishes.

This music, tender and tempestuous, tranquil and passionate, heart-reaching, potent, overwhelming: this music which eludes metrical discipline, rejects the fetters of rhythmic rule, and refuses submission to the metronome as if it were the yoke of some hated government: this music bids us hear, know, and realise that our nation, our land, the whole of Poland, lives, feels, and moves, “in Tempo Rubato.” [5] Why should the spirit of our country have expressed itself so clearly in Chopin, above all others? Why should the voice of our race have gushed forth suddenly from his heart, as a fountain from depths unknown, cleansing, vital, fertilising? We must ask this of Him Who alone can open the secret womb of Truth, Who has never yet told us all, and Who perhaps will never tell us.

The average Polish listener, unfamiliar with the art of music, hears the masterpieces of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven with indifference, at times even with impatience. Polyphonic ingenuities, wealth and variety of harmonic intricacies, lucid enough to the trained understanding, are inaccessible to his ear; his mind loses its way in the mystery of figures; his attention wanders and strays amid the marble forms of the beautiful but German Sonata; he confronts the amazing structures of the classic symphony chilled and ill at ease as in a foreign church; he cannot feel the Promethean pangs of the world’s greatest musician.

But let Chopin’s voice begin to speak and our Polish listener changes immediately. His hearing becomes keen, his attention concentrated; his eyes glisten, his blood flows more quickly, his heart rejoices although tears are on his cheek. Be it the dancing lilt of his native Mazurka, the Nocturne’s melancholy, the crisp swing of the Krakowiak: be it the mystery of a Prelude, the majestic stride of a Polonaise: be it an Etude, vivid, surprising: a Ballade, epic and tumultuous: or a Sonata, noble and heroic; he understands all, feels all, because it is all his, all Polish…

Once more his native air enfolds his being, and spread before him lies the landscape of his home. . . Under the sad sky’s vague blue, he sees the wide plains upon which he was born, the dark edges of distant forests, plough-lands and fallow lands, fruitful fields and sterile sandy stretches… A gentle hill has risen, at whose feet the twilight mists hover mysteriously above the green hollow of the meadows; the gurgling of brooks reaches his ears, the scant leaves of the birch rustle tearfully, a soft wind plays in the fall poplars, strokes the green waves of yielding wheat; a perfumed breath blows from the ancient pine forest, wholesome, rosinous. . . And all this becomes peopled by strange legendary shapes such as, long ago, his fathers conjured to sight: unearthly half-forgotten beings come to life again in the spring night. . . A Scherzo! he beholds the wild frolics of demi-god and goddess. . . Phantoms without number haunt field and meadow; in the dense thicket were-wolves struggle; roguish imps are at their pranks; little hovering love-sprites rove a-wooing, returning ever to encircle their Queen of Love, Dziedzila, [6] and to hear that deathless song which, long ago, burst her bosom open and laid bare to all men’s sight a heart broken with loving – the heart of Poland.

Now and again Perun [7] the immemorial raises his voice and thunders, gloomily, threateningly, solemnly, . . . The holy groves tremble, the scared elves vanish from the surface of the lake, and lightning flashes burn the sky. A storm has broken, sudden terrific, driving, pursuing, shattering; caught in the tempest’s whirling blast, the proud fanes of the Druids totter and fall . . .

Our Pole listens on. Summer’s breath on the fields of his fathers blows softly round his soul. The sea of golden wheat has dried away, the shocks and sheaves are standing, the sickle is at rest. Light quail and graver partridge are on the wing, searching the rich stores of the stubble. Waves of harvest song are on the air: from marsh and pasture comes the echo or the herdsman’s pipe: not far away, there is hum and bustle at the way-side inn. The fiddlers play dexterously, they play by ear, thrusting in a frequent augmented fourth, familiar, racial: a rude bass-viol supplies a stubborn pedal: and our folk dance briskly, stridingly, or sing slowly, musingly – a healthy folk, wayward, merry, yet soaked with melancholy. . . In the little church across the road an organ sounds, poor and humble. . .

Away there, in the stately Manor, lights are flaring in the halls; great nobles, county electors maybe, are gathered here in a coloured, glistening throng. Music sounds. . . My Lord Chamberlain, or whoever present be most dignified of rank, steps forth to lead the Polonaise. There comes the clank of swords, the rustle of brocaded silks against wide sleeves, purple lined. With dashing step the couples march on proudly, while soft smooth words begin to flow towards fair cheeks and lovely eyes – the glib words of the old Polish tongue, well interspersed with many Latin, and with here and there, perhaps, a timid touch of French. . .

The dance has ceased; and now an old man, long-bearded, white-haired, silver-voiced, tells some misty tale to the sound of bag-pipe, lute, and harp. He tells of Lech, Krak, and Popiel, of Balladyna, Veneda, Grażyna. . . [8] he chants of lands beyond the seas, of Italian skies, of jousts and troubadours, he sings of the White Eagle, of Lithuania’s Horseman, [9] of victorious encounters and of battles lost, of vast immortal struggles, unended and unsolved. . . All listen and all understand. . . Out in the garden where the air is sweet with breath of roses, with sigh of jasmine and of lily, a lovely daughter of the house, under the shielding murmur of the limes, caught in a starry Nocturne whispers to some sad youth the tender sorrows of the summer night. . .

Summer has passed now, and so have many summers. Gone are the armoured knights and their conquering marches, fallen are the wings of the intrepid hussars who once victoriously ploughed the Baltic waves; the manhood of the Lancer’s nobles charges is now no more; nothing remains but a memory fast-held in the annals of our glory. . . Autumn has come – here are Preludes that almost seem to be Epilogues. Is this Life’s autumn? No; it is rather Autumn’s life that here begins. The days are shorter, the light wanes, fair times and merry are rarer now. Yet, when the sun shines forth in its glory, it is hard to tear oneself away from so much wealth of matchless colour, and to face consciousness of dusk, of the outweighing shade. The old timepiece that measured fairer days for our grandfathers and great-grandfathers now solemnly strikes a late and midnight hour. The gloomy wind howls in the empty chimney; one hears the measured drops of the autumn rain, the soft thud of withered leaves falling to earth, the mournful rustle of the orphaned branches.

The old graveyard is full of ghosts; amid the ancient mounds and hillocks phantoms creep, spectres fulfill their shadowy rights. What ghost was that? Whose spirit there went past? Was this Żółkiewski? [10] Or Czarniecki’s noble shade? [11] Were these the traitor brothers, Bogusław and Janusz Radziwiłł? [12] or Radziejowski of equal stain? [13] Was not this the lofty figure of Kordecki – luminous still in this hour of darkness with the light of Jasna Góra? [14] Was this not Siciński, of dishonoured bones? [15] Here perhaps Rejtan the patriot, or Potocki the renegade Marshall of Targowica? [16] here perhaps Bartosz Głowacki, the peasant-hero, or Szela the infamous. . . [17] Ah, no! these names belong to history, for history, although she stands at the threshold of immortality a fastidious guardian, admits to her sanctuary good and bad alike, provided only they be great.

But the music we speak of is a part of immortality itself, and harbours all, great or little, strong or humble, famed or nameless, stripping them only of the errors and guilts of their earthly covering, and bringing them forth anew from the cleansing depths of the soul, beautified, ennobled.

Notes

[1]. Chopin: A Discourse is the English translation of this text, originally published in London by W. Adlington (1911) and simultaneously in New York by H. B. Schaad. The text also has French, German and Polish editions. Laurence Alma Tadema was a daughter of English painter, Laurence Alma Tadema (1826-1912) who befriended Paderewski in 1890s and created his portrait. Laurence Alma Tadema remained Paderewski’s most faithful admirer until the end of her life; she never married and was active in causes dear to the pianist, especially of Poland’s independence. She was active as a poet (“If no one ever marries me”) and writer (“A knot of ribbon” in Nineteenth Century Short Stories by Women: A Routledge Anthology, ed. Harriet Devine Jump; London and New York: Routledge, 1998). [Back]

[2]. Lemberg is the German name for the Polish city of Lwów, now a part of Ukraine and known as Lviv. [Back]

[3]. Paderewski was the initiator and sponsor of this patriotic and anti-German event; his Grunwald speech is reprinted in the current issue of PMJ.[Back]

[4]. The use of the term “race” in reference to “nation” or “ethnicity” was widespread at the end of 19th century; popularized by French philosopher Hippolyte Taine (1828-1893) whose Philosophy of Art was the most influential study of this subject at that time. [Back]

[5]. Paderewski’s essay on “tempo rubato” is reprinted in the Polish Music Journal vol. 4 no. 1 (summer 2001).[Back]

[6]. Dziedzila – a goddess from pre-Christian Slavic pantheon; see Barford, The Early Slavs (New York: Cornell University Press, 2001).[Back]

[7]. Perun, also known as Svarog, the main deity in Slavic pantheon, associated with oak trees, lightning, fertility, and rain; the patron of the Kiev princes. See Barford, The Early Slavs,, op. cit., 194. [Back]

[8]. Lech, Krak, Popiel, Balladyna, Veneda, and Grażyna are figures from Polish national mythology. Lech was the legendary founder of Poland, a country known as “Lechistan,” Krak was the king of Poland’s first capital, Kraków; Popiel was a cruel king in Gniezno, punished by being eaten by mice; Balladyna and Veneda were pagan heroines re-introduced into the mythical lore by romantic poet, Juliusz Słowacki; Grażyna was a legendary Lithuanian princess who chose death over betrayal of her nation, a heroine of Adam Mickiewicz’s epic poem. [Back]

[9]. The White Eagle on a red background is Poland’s national emblem; the Lithuanian emblem is an armed horse-rider, this emblem is called the Pogoń. [Back]

[10]. Stanisław Żółkiewski (1547-1620) was a military commander, the leader of the Polish army, and a heroic participant in wars against Muskovy, Sweden and Turkey; he died on the battlefield. [Back]

[11]. Stefan Czarniecki (d. 1703) was the commander of the Polish army in wars against the Cossacks, Tartars, and Muskovy, as well as the Swedish invasion; renowned for liberating Warsaw and victories in battles against the Swedes. [Back]

[12]. Bogusław (1620-1669) and Janusz (1612-1655) Radziwiłł were Lithuanian princes who took the side of the Swedish king, Karol Gustav, against their Polish ruler in the war of 1655. Due to their actions, Lithuania left the Union and Poland was greatly weakened and almost destroyed.[Back]

[13]. Hieronim Radziejowski (1612-1667), in 1652 banished for having offended the king; in 1655 returned with the Swedish army whom he assisted against his homeland. [Back]

[14]. Jasna Góra [the Bright Mount] is the popular name of the shrine of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Częstochowa; the icon preserved there is regarded as the patron of Poland and called, due to the darkness of the varnish, “The Black Madonna.” Father Augustyn Kordecki (1603-1673) of the Pauline order was the abbott at the shrine during the Swedish invasion and is regarded in popular mythology as a savior of the country due to his resistance and courage in defending the shrine in 1655 (a site of a reputed miracle). Historical records show that Kordecki was more interested in safeguarding the interests of the monastery than in the Polish cause and that his attitude towards the Swedes was servile and not heroic (he tried to negotiate settlements with the assumed new rulers of the country, pledging allegiance to the Swedish king). Kordecki’s apparent heroism was portrayed in the popular novel Trilogy by Henryk Sienkiewicz while the historical facts remained unknown.[Back]

[15]. Władysław Siciński (d. 1664), a representative at Seym (Polish parliament), in 1652 used his liberum veto (free vote) for the first time to break up the Seym and make it impossible for Poland to be governed during the Swedish threat; apparently paid by Radziwiłł.[Back]

[16]. Targowica was the site of a confederation of Polish aristocracy aimed against the May 3 Constitution of 1791; its activities in 1792-93 resulted in an invasion of Poland by Russia; put an end to the social reforms declared by the Four-Year Seym; and resulted in the complete ruin of the country – divided between three neighboring empires in 1794. Count Stanisław Szczęsny Potocki (1752-1805) was one of its leaders; in 1794 sentenced to death for treason. Tadeusz Rejtan (1742-1780) was a representative at Seym who tried to prevent the partitions of Poland in 1773-1775 (he later committed suicide). Rejtan is famous due to a monumental historical painting by Matejko.[Back]

[17]. Bartosz (rather: Wojciech) Głowacki (1758-1794) was a peasant leader in the Kościuszko Insurrection in 1794; the last effort to save the country. Głowacki’s peasant troops had weapons remade from scythes; participated in an attack at Russian canons on Racławice and was made an officer of the Polish army. Jakub Szela (1787-1886) was a leader of a peasant uprising against the gentry in Galicia in 1946; scores of manors were attacked and their inhabitants murdered.[Back]