by Egbert Swayne [1]

Unquestionably Mr. Paderewski is the most conspicuous and picturesque figure in the musical world, just now. In this respect he forms a comely successor to the late Abbe Liszt, who was nothing if not picturesque. One of the features of the immediate American future of opera will be the production of Paderewski’s Manru, which is scheduled to take place early in February, at the Metropolitan Opera House. The piano score of the opera has lately been published by the house of Schirmer, and I have been delighted in reading it through. The conception of the plot is Paderewski’s, the design being to afford opportunity for introducing some of those picturesque folk tone types of melody, of which Europe still has several varieties unknown to high art. Fundamental to a correct understanding of the opera, Mr. Krehbiel, [2] the English translator, has prefixed an extract from Mr. C. G. Leland’s book, The Gypsies. [3] He says:

If you look wistfully at these ships, far off and out at sea, with the sun upon their sails, and wonder what quaint mysteries of life they hide, verily you are not far from being affected or elected unto the Romany. And if, when you see the wild birds upon the wing, wending their way to the south, and wish that you could fly with them, anywhere, anywhere over the world and into adventure, then you are not far in spirit from the kingdom of Bohemia and its seven castles, in the windows of which Aeolian harps sing forever. Now, as you wander along, it may be that in the wood and by some grassy nook you will hear voices, and see the gleam of a red garment, and then find a man of the roads with a dusky wife and child. You speak one word, “Sarishan!” and you are introduced. These people are like birds and bees, they belong to out of doors and nature. If you can chirp or buzz a little in their language and know their ways you will find out, as you sit in the forest, why he who loves green bushes and mossy rocks is glad to fly from cities, and likes to be free of the joyous citizenship of the roads, and everywhere at home in such boon company.

Of the story Mr. Krehbiel speaks as follows:

The story at the base of Manru is romantic in character and scene and tragical in outcome. In a general way it illustrates that irrepressible desire on the part of the Gypsy to wander, which Mr. Leland has characterized in his books on the Romanys; also, in an allegorical way, the contest supposed to exist between the artistic and domestic natures. The plot was borrowed from a Polish romance. [4]Manru has won the love of a fair Galician maiden, [5]Ulana, and married her Gypsy fashion. After a space she returns to her native village, among the Tatra mountains, to seek her mother’s forgiveness and help. She receives instead the contempt of the villagers and a mother’s curse. Her former friends taunt her with a song which tells of the inconstancy of all Gypsies under the influence of the full moon. Having already observed signs of uneasiness in her husband, Ulana seeks the help of Urok, a dwarf, who has the reputation of being a sorcerer, and who loves her. From him she obtains a magic draught, and by its aid wins Manru back to her side for a time. Alone among the mountains, however, the baleful influence of the moon, the charm of Gypsy music, and the fascinations of a Gypsy maiden, break down his better resolutions and he rejoins his black-blooded companions. Oros, the Gypsy chief, himself in love with the maiden Aza, opposes Manru’s rehabilitation in the band, but through the influence of Jagu, a Gypsy fiddler, he is overruled, and Manru is made chief in Oros’s stead.Oros takes his revenge by hurling his successful rival down a precipice, a moment after a distraught Ulana has drowned herself in a mountain lake.

Concerning the musical handling the following particulars may be of interest: The first act, naturally, is devoted to giving things a start. The work opens with a harvest festival of the villagers, in which naturally a good deal of simple and pleasing music of a quasi folk song and rustic character is introduced, along with more or less dancing, picturesque costumes, and the like. The elements in the real action here are first the chorus, which has a great deal to do all along, and is rarely off the stage throughout the act. As the chorus sings, Hedwig, mother of Ulana, sits on one side and muses upon her absent daughter. The music to which she meditates is of no great importance, but the flute gives the characteristic Gypsy motive, of which a great deal is made later. For instance, Ex. 1 shows the manner of handling of Gypsy music in Manru (see Example 1).

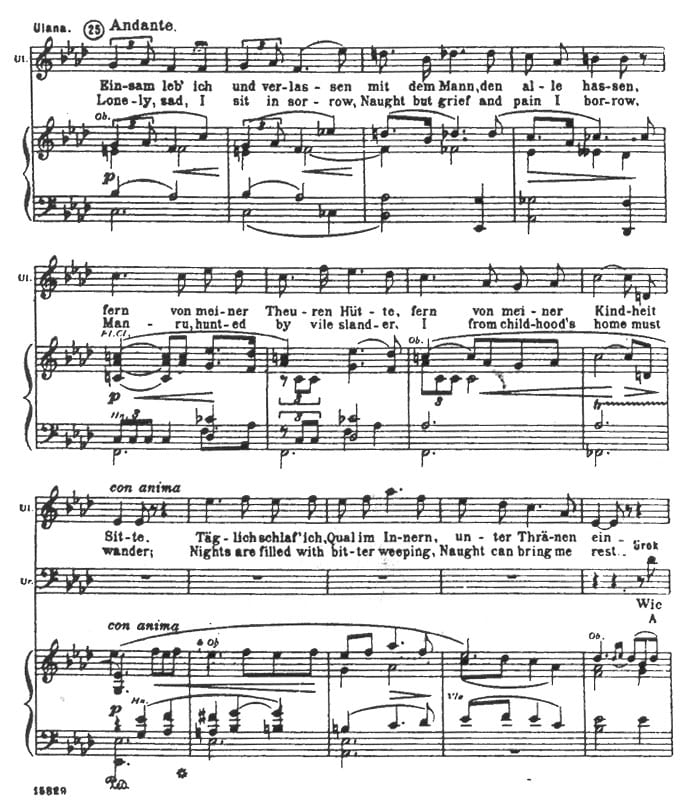

The cheerful music goes on more and more, Hedwig still throwing in passages of meditation until at length Urok comes in, only to receive the hateful greeting which a peasant people knows so well how to afford an unwelcome visitor, who is not only misshapen in body but evil and unlovely in mind. They call him names of spite, and many pages are thus consumed. Meanwhile Urok is full of the memory of Ulana. He is overheard and the chorus takes up this new subject of reproach. After a while Ulana herself approaches; she is greeted with contempt, even her mother disdaining to promise welcome or assistance. After some time of this “broken music,” as Shakespeare called it, Ulana approaches her mother’s hut, where she is seen but not recognized as a daughter. Here comes the first great moment of the music: it is the appeal which Ulana makes to her mother. Example 2 shows its manner and it is plain that a really great singer has here an opportunity for pathos such as many operas fail to afford (see Example 2).

It will be observed that between the music in Example 1 and this in Example 2 no less than sixty pages of vocal score have intervened. Evidently a blue pencil will find application in this part of the work. Her mother is won by her entreaties but declines to permit her to remain unless she will sever herself from her husband, which she declines to do. She therefore receives her mother’s curse, after which the villagers begin again, and a scene intervenes between Ulana and Urok, who urges his own love. This long argument finally ends by his succumbing to the “goo-goo eyes” which Ulana turns upon him, and he agrees to furnish the philter, trusting that in some way it may come back to his own benefit, his previous operatic experience having shown him that philters are more uncertain in their action than a good revolver in the hands of a woman. The chorus returns and the act goes on with a ballet. Into the midst of this rejoicing, which is partly a mischievous restraining of poor Ulana, Manru comes, requiring his wife to follow him. At length they depart amid the curses of the pleasing populace. And so the act ends.

Urok has a good part, although a very unlovely one. Ulana has but little to do , but this is of good quality. There is plenty of chorus singing and dancing and not a little of the cumbersome horse play which operatic composers consider necessary. Even Wagner could not get rid of it. The sensuous maiden in tricot he often managed to avoid; but the chorus still found ways of putting in its say.

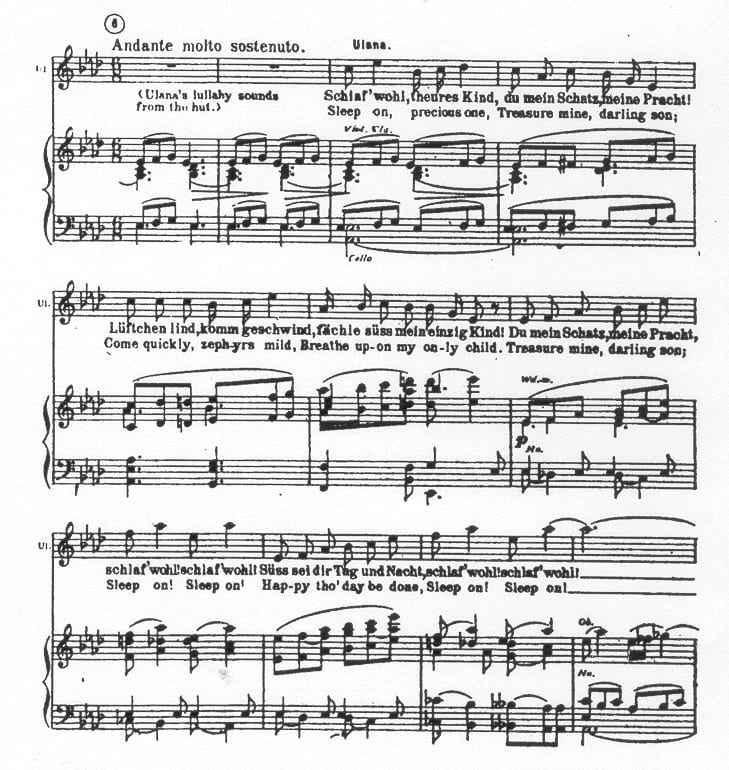

The second act opens with a scene in the mountains, Manru’s court-yard, in the background a forest of firs; to the right a small smithy, a la Siegfried. Manru is working at the forge. Blessed and unhoped for opportunity for the composer. He can play the hammer. The idea is novel. Much can be done with a hammer. Manru sings as he works, at first merely in short phrases, relating his joy in his wife and their child, and to emphasize the idea their figures show through the open door. Despite his joy in his wife, Manru deplores the loss of his roving pleasures. Just here, when the husband’s rising uneasiness begins to be felt more and more, Ulana sings her lullaby. It is a most lovely strain. Example 3 shows the beginning (see Example 3).

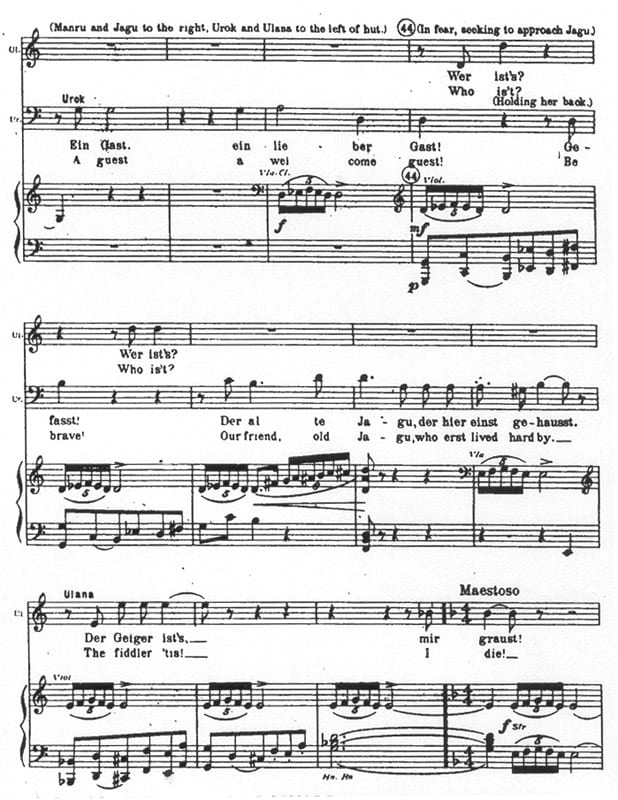

Then follows a long duet between Manru and Ulana; he showing more and more his dissatisfaction with his present lot and his roving tendencies, even though the gallows should afterward his portion. Meanwhile poor Ulana does the best she can with her sweet little broom to push back this incoming tide of unholy aspirations. As usual the preacher gets the better of the argument only to fall into a worse affair, for Manru raises his hand to strike Ulana. Just here Urok comes in and withholds the blow. A dramatic scene follows in which Urok skillfully plays upon Manru’s irritation and at last, despite Ulana’s efforts, Manru is more and more inclined to depart. Then comes from the distance the sound of Gypsy violin, and after much struggle he at length rushes off to find the band of Gypsies. After his departure Urok at length gives Ulana the magic philter.

The Gypsy music becomes plainly out in the next scene, which begins by the entrance of Jagu, the Gypsy fiddler, from the forest. He is greeted by Urok and the music is characteristically Gypsy (see Example 4).

Later Manru has his great solo, in which all the forces of his wild nature answer within him to the inspiration of the shining moon, the swelling buds, the mysterious awakening of Spring, and so on. This is followed by many taunts from Urok, who calls up the image of a fascinating maiden of whom Manru is thinking, until at length he is driven away. Then Ulana gives Manru a drink of wine, into which the potion is poured from the philter. The act closes with a very long and very impassioned duet of reunited love. Quick curtain.

The third act is preceded by an elaborate prelude in which all the various motives find play, particularly those of Gypsy character. The curtain rises upon a lake in the foreground and a romantic mountain landscape in the background, with practicable paths, and so on. Manru from the mountain calls for air. He has come from the cottage, which seems to him smaller than ever. He feels the moon behind her cloudy veil. So does the music. In this inopportune moment the distant voice of the Gypsy enchantress is heard, and the sound of the band arranging to set up their camp. Manru, torn with all the driving impulses of his wild blood, remains upon the stage, because it would not be effective to go off.

He speaks of what is surging through his troubled heart. Meanwhile the impassioned Gypsy music goes vigorously on, changing now and then into a strain of something softer. Manru quiets himself and lies down to sleep. Softer and more beautiful moonlight now floods the stage, the face of the sleeping Manru and the partiture of the opera. A magic veil is cast over all. Here is Paderewski’s great opportunity to be romantic and expressive. He has recognized it. The full moon is clouded over and again revealed; the music participates. A storm springs up in the orchestra and the wind machine begins to turn. At last comes the strain of the Gypsy march, to which the band moves onwards towards their camping ground by this secluded lake. One page will serve as an example. See Example 5).

The body of the march begins at the guiding number 48, in the second line of the music. No doubt this is scored with all the art of a modern Gypsy painter. Then follows a chorus of Gypsies, and at length a woman recognizes the sleeping Manru as the missing member of their band.

When he awakens his opening eyes rest upon the fascinating Asa, that typical enchantress without which no Saracen or Gypsy novel is at all complete. She is full of rich and warm blood, fair and voluptuous to look upon, and full of the mysterious health of open air and natural life.

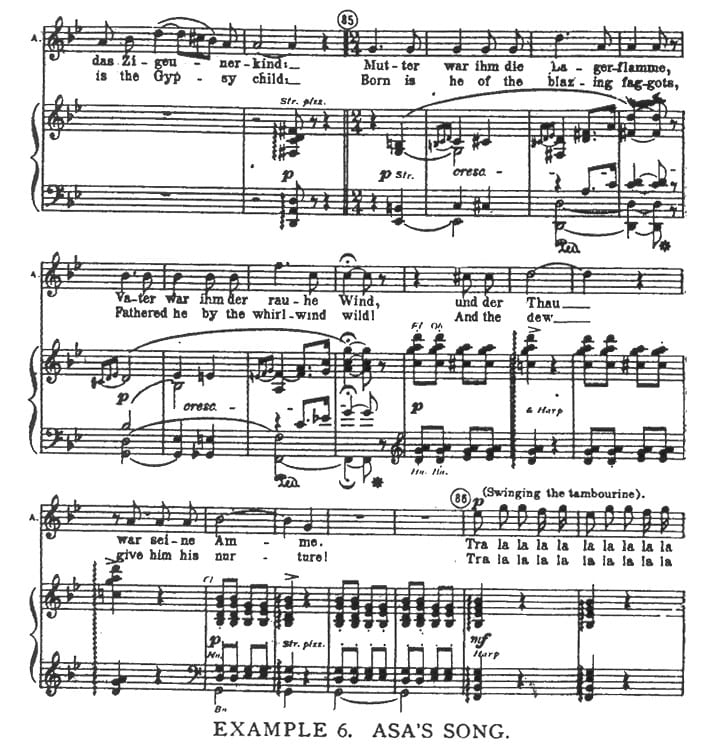

From this point everything is already settled. Naturally, Manru meets a certain ill reception from the chief Oros, who has a long scene of the “heavy old man” type. Asa greets Manru and aside tries to bring him back again to his allegiance to the band. He remembers his love and his wife and a long duet follows in which the opposing influences are unfolded. Asa sings. (See Example 6).

Later the Gypsies commence a dance and after a little [while] Manru throws his arms around Asa and is swept away in its circling mazes. Meanwhile Manru is elected chief and takes command. Urok comes in as a messenger from Ulana and she appears later with a short but powerful solo immediately preceding her self-destruction. The opera is now done and the final scene probably occupies but a moment, and few will ever see it, owing to the general rush for wraps and carriages.

Undoubtedly the chief characters have a great deal of effective music in this opera, and the scoring is said to have been done with great care and skill. All who have fallen under the magic of Mr. Paderewski’s personality, and who take pride in the great world-fame which this still young artist has acquired, will hope that this work may prove a success and lead to many others. [6]

Notes

[1]. Original publication data: Egbert Swayne, “Paderewski’s ‘Manru,” Music vol. 21 (January 1902): 153-162. There is no information about this music critic in RILM or other standard databases. According to Periodicals Contents Index, Swayne was a frequent contributor to Music, having authored 37 articles and book reviews for that journal. Music appeared in 1892-1902 and Swayne’s texts were featured in volumes 5 to 22. He dealt with a variety of topics, including the opera (Verdi; Wagner; opera singers), music education, pianists and pianos, recent developments in composition, etc. [This and all subsequent notes are by the editor, Maja Trochimczyk]. [Back]

[2]. Henry Edward Krehbiel (1854–1923) was a well-known American music critic and historian. He worked for the New York Tribune and published articles in various journals, e.g. Scribner’s Monthly, Music, etc. Krehbiel was interested in new music, promoting especially the works of Wagner, Brahms, and Tchaikovsky. He wrote numerous music monographs, including studies of music in the classical period, a history of the piano, Afro-American folksong, etc. He also annotated concert programs (including many of Paderewski’s recitals), and edited the English version of Thayer’s Life of Beethoven.[Back]

[3]. Charles Godfrey Leland, The Gypsies, 7th ed. (Boston, New York : Houghton, Mifflin and Co., 1898). [Back]

[4]. Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, Chata za wsią [A hut beyond the village], a novel in three volumes. First published in 1854-1855; the book with numerous reprints. It is possible that the libretto of Manru was based on a 1872 edition, revised by the author (Lwów : W ksieg. Gubrynowicza i Schmidta). Józef Ignacy Kraszewski (1812-1887) was a prolific writer of novels, frequently dealing with folk culture and national themes. This novel also provided the source for Zygmunt Noskowski’s “folk drama” postdating Paderewski’s Manru: Chata za wsią, folk drama in five acts with song and dance; written by Zofia Meller and I. K. Galasiewicz, with the music of Zygmunt Noskowski (Chicago: Druk. i nakł. Władysława Dyniewicza, 1908). [Back]

[5]. “Galician” means from “Galicia” – the southern and south-eastern part of Poland; during the partitions a semi-autonomous province in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Tatra Mountains are located in this area. The shifting of the novel’s action to this area may have had musical reasons – recent fascination with the original folklore of the inhabitants of the Tatra Mountains (górale); see Timothy J. Cooley, “Authentic Troupes and Inauthentic Tropes: Performance Practice in Górale Music,” (Polish Music Journal 1 no. 1, summer 1998).[Back]

[6]. Due to the opera’s hostile reception in Germany and other factors, Paderewski did not again compose for the operatic stage. His concert compositions also end with a patriotic song, as he decided to sacrifice his career as a composer to serve the cause of Poland’s independence.[Back]