An Overview [1]

by Linda Schubert

Abstract

After World War II, well-known Polish composer Henry Vars (known in Poland as Henryk Wars, 1902-77) settled in Los Angeles to resume his work as a film composer (he is probably best known in the United States for his music for the film and TV series about a dolphin, Flipper). An important pioneering film composer in Poland, who scored one out of every three Polish films made before World War II, Vars ultimately contributed music to at least 90 films in his career. He also penned a number of popular songs, Polish “golden oldies” performed to this day. As an émigré in Hollywood Vars was required to re-establish his identity as a professional composer to make his living in the film industry. This paper provides the most complete filmography now available of Vars’ American scores, describes his career in the U.S. and discusses several cues from films illustrating some of the new musical projects and tasks (such as team composing and writing for Westerns and horror films) that Vars undertook in the U.S., including Chained for Life, The Big Heat, The Unearthly, and Seven Men From Now.

Article

I. Introduction

Polish composer Henry Vars (1902 – 77) wrote songs that were widely popular between the wars, as well as the scores for over one third of the sound films made in Poland before World War II. [2] Vars moved to the United States in 1947, and eventually composed music for many American films as well as several television shows. He wrote scores and cues—often uncredited—for a variety of pictures including westerns, mysteries, crime, and horror films, and is perhaps best known in the U.S. as the composer for the film and television series Flipper. In the U.S. Vars worked smoothly within film music conventions that emphasized melody, leitmotifs, and late Romantic instrumentation and harmonic movement. Vars was, however, unique in the wide range of musical experience that he brought to his scores, having worked not only as a conductor and pianist but as a composer of concert hall works, jazz pieces and popular songs. Despite his accomplishments Vars is not widely known by mainstream audiences in the United States, though his music—particularly his songs—is still played and enjoyed in Poland. This paper offers a biography, together with an overview of his American film scores, including a (brief) discussion of research issues. Vars’ American filmography follows.

II. Vars in Poland

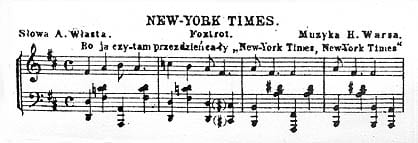

Born to a musical family, as a young man Vars (originally Warszawski, shortened to “Wars” for the Polish stage and finally to “Vars” in the U.S.) was originally interested in drawing and began studies at the Fine Arts Academy in Warsaw. [3] However the well-known composer and conductor Emil M≥ynarski, director of the Opera House (Teatr Wielki) and Music Conservatory in Warsaw, offered Vars a scholarship to study at the Conservatory, where Vars finished in 1925. [4] He also spent one and a half years in military service, graduating from Officers’ School in W≥odzimierz. [5] After leaving the service, Vars began to write songs influenced by American jazz. According to music commentator Ryszard Wolanski, the young composer’s first popular song was “New York Times” composed in 1928 (see Example 1). Besides being an active performer and conductor—playing piano at the “Morskie Oko” cabaret in Warsaw, and directing the choir at the cinema-theater, “Hollywood” [6]—advertisement examples of tunes from the backcovers of Polish sheet music of the time show that Vars also worked as an arranger (see Example 2). [7]

As Wolanski has noted, Vars’ Polish film scores became an important source of many of his songs and other short pieces (such as tangos) which often took on a popular life of their own, independent of the films, and were published as sheet music. Vars’ first film score, composed in 1930, was for one of the earliest Polish sound films: Na Sybir, directed by Henry Szaro. Between 1930-39 Vars became one of the most important composers for Polish film; of the 150 films produced in Poland before the war, Vars composed the score for one out of every three. [8] Consisting of melodramas, light comedies, romances and musicals, these early films were very popular within Poland—though the international film world thought little of them at the time. (To this day these films have received little attention in film histories, and none in film music histories).

Vars’ scores for His Excellency the Shop Assistant (1933) and Upstairs (1937) were inspired by American jazz, as opposed to his later American scores which (thus far) appear firmly rooted in late European symphonic style, following prevailing scoring practices for films other than musicals. One gently satirical source (diegetic) jazz cue from Upstairs, for example, is heard when an elderly man playing “light classics” with his friends is disturbed by the young man “upstairs” who plays jazz with his friends, and is scored for two alternating—and opposing—groups. The classical group is made up of a violin, cello, flute and bassoon, while the jazz group consists of a piano, trombone, trumpet, clarinet, saxophone (the latter seen but not heard) and drums (heard but not seen). In the ending scene of the film, set in a radio station, all the musicians have become friends, and the source music combines the classical and jazz groups in friendly, if frenetic, unity.

World War II

It is not entirely clear what Vars’ last film score was before World War II. According to the composer’s own personal list of his Polish films (clearly compiled later in the U.S. and known to be missing some films), his last film was Seventh Class Satan of 1939. After this he became a cadet in the Polish Army and was captured by the enemy soon after. Vars was Jewish, and, aware of his danger, managed to slip away from the prisoners’ train during a rest stop and made his way by foot to the city of LwÛw. [9] There, in 1940, he organized a music/theatrical group called the “Polish Parade,” and began to tour the U.S.S.R., where he befriended Dunajewski and Khachaturian. [10]

According to Wolanski, it was late in 1941 when “Polish Parade” joined the Second Polish Corps in the U.S.S.R. lead by General Anders; in 1942 the Second Polish Corps left for the Middle East. [11] After training with British forces in Persia, Iraq, Egypt, and Palestine, they headed for Italy in 1943, going on to win the battle of Monte Cassino in 1944. Along the way, “Polish Parade” received first prize in a contest of Allied Forces artistic groups. They often performed under fire and earned the title “Ambassadors of Hope.” [12] In 1946, seven years since his last film score, Vars composed the music for the Roman picture The Big Trail, a film about the war effort.

III. Vars in the United States

After the war Henry and his wife Elizabeth did not wish to return to communist-controlled Poland and decided to come to the United States. Arriving in New York in 1947, Mrs. Vars recalled that their situation was difficult. Her husband had a letter of recommendation from Arthur Rubinstein, though it is unclear to what extent this letter may have helped them. She also remembered that when Vars joined the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) in 1950, Ira Gershwin was his sponsor. [13] They finally settled in Los Angeles, where Vars pursued film composing while Elizabeth took a job in a drapery shop to make ends meet.

Over the years Vars would score westerns for Batjac Productions, films directed by Andrew McLaglen, children’s films such as Flipper, individual cues to numerous “B” pictures for Universal and Columbia, and several films and television shows for MGM In the 1960s. (He apparently scored only one film—Silver City—for Paramount, and did no work for RKO.) In 1967 Henry and Elizabeth visited Poland for the first time since the war. Wolanski mentions that he also visited his sister in Nice and traveled to London as well. Coming back to California, Vars may have been making plans to return permanently to Europe. [14] He remained, however, in Los Angeles, continued composing for films, and returned to his early interest in art, in particular sketching political caricatures. His last score was for McLaglen’s Fool’s Parade, starring Jimmy Stewart, made in 1971 (these cues are now housed at the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming, Laramie). Henry Vars died in 1977, having scored or contributed cues to over 90 films in his international career. Among the honors he received in his life, Vars was awarded the Cavaliere de Croce Italia as well as an award from President Truman. [15]

The studios that commissioned the most cues from Vars in the United States were: Columbia (8 films), Universal (7, perhaps 8), and Twentieth-Century Fox (5). Following are MGM (4), United Artists (1) and Paramount (1). Most of Vars’ work, however, was commissioned by independent makers who then distributed through major studios; these independents included Batjac (5 films), Allied Artists, Bischoff-Diamond, Gordon McLean, and Fairway International.

Vars’ first film score in the United States was for another independent, Classic Pictures, for Chained For Life in 1951. A crime drama about conjoined twins in show business (one who falls in love, the other who murders the lover), Chained For Life is a curious combination of exploitation film and pleasant musical. The twins are singers in vaudeville, and consequently there is plenty of opportunity to present acts and songs, from an accordionist playing “The William Tell Overture” to an exotic gypsy woman singing in a smoky cafÈ. In the midst of all this the twins sing several songs including Vars’ “Every Hour” and “Never Say You’ll Never Fall in Love”. (Their rendition of “Every Hour” takes place during an audition scene where the pianist who plays for them may be Vars himself.)

Vars came to Los Angeles looking for work as a composer when the film industry was losing much of its audience to television and cutting budgets to survive. American-born composers new to Hollywood were finding it hard to get employment, and new ÈmigrÈ composers found it almost impossible. Vars therefore took additional work as a copyist, and after scoring Chained For Life he also orchestrated several pictures: Gog (1954), The Phoenix City Story (1955), and Bullet for Joey, (1955), all with scores by concert pianist and film conductor/composer Harry Sukman. [16] (Gog, a science fiction film, was written by Ivan Tors, who later became known for television shows in the 1960s featuring animals, including Flipper.)

Batjac Productions

In 1955, after scoring the novelty picture Ski Crazy!, which featured filming done with a camera on skis, Vars had his first important break with Batjac Productions. The company, originally named Wayne-Fellows Productions, had been formed in the early 1950s by John Wayne and Robert M. Fellows, a former producer at RKO and Paramount. Wayne later bought out Fellows’ interest and renamed the company “Batjac,” after the name of the Dutch trading company in the film Wake of the Red Witch. Wayne’s younger brother Robert E. Morrison became a producer for Batjac, as did Andrew V. McLaglen, the son of actor Victor McLaglen (who had been a regular with John Ford’s company). Later in the 1960s, Michael Wayne also produced a number of Batjac films starring his father. [17]

Over the years the Batjac films starring Wayne were scored by a number of established composers in the industry, including Elmer Bernstein, Dmitri Tiomkin, and Roy Webb. Vars scored five of the seven Batjac films in which Wayne did not appear or receive on-screen credit as a producer. Of these five, the first to be released was the western Seven Men From Now (1956), directed by Budd Boetticher, and included Andrew McLaglen in the group of executive producers (this film received considerable attention a few years ago when it was restored by UCLA Film and Television Archives). At the time of its original release, reviewers for both the Hollywood Reporter and Variety thought the music, particularly Vars’ song “Good Love” worth a mention. The review in Variety, designated only as “Brog.”, observed that “Henry Vars’ score goes with the story mood, as does the title he wrote with By Dunham. Only a snatch of another song, ‘Good Love,’ is heard.” [18] The anonymous reviewer for the Hollywood Reporter commented that “There is a title song for the picture by Dunham and Henry Vars which may help in its exploitation.” [19] Of the other four films, Gun the Man Down was McLaglen’s first directing effort; Man in the Vault was also directed by McLaglen; China Doll was directed by Frank Borzage; and Escort West was directed by Francis D. Lyon. Vars later worked with McLaglen at other studios on Freckles, The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come, and Fool’s Parade.

Team Composing

For many American films made during the 1930s through the 1950s, a single composer for a dramatic score was often the exception rather than the rule. Scores for the many “B” movies being cranked out were often assembled by teams of composers, with composers selected, assigned work and coordinated by a Music Director or Supervisor. [20] Film composer David Raksin has described the process as he personally experienced it in the late 1930s: after breaking the film down into the sequences that would receive music and deciding what kind of thematic material was needed, the team wrote sample themes and selected the ones to develop. This music was photostated and distributed to the group. The reels were divided up among the composers to work on and soon after that (often the next morning) they handed over their sketches to the orchestrators who produced full scores to send to the copyists. [21]

It was the Music Director who actually received screen credit for the music. The cues themselves were owned by the studio, not the composers, and after use they were stored at the studio. This practice of maintaining a collection of stock cues (reminiscent of the music libraries held by movie theaters of the silent period) made cues easily available for re-use in other films. This meant, in turn, that some later films had scores made up of cues by various composers, but that this music was not originally composed for the film by a team. Rather, the cues were assembled from the library by a Music Director.

Although he wrote complete scores for which he received screen credit, Vars, too, experienced the “team composing” system first hand, and wrote many sets of film cues for which he did not receive screen credit. In many cases (as can be seen from checking ASCAP records) he contributed original cues to projects with other composers and/or pre-existent music already assigned, and as described above, the Music Director received screen credit. Vars, for example, contributed original cues to Columbia’s The Big Heat (1953), directed by Fritz Lang, which also included stock music by Arthur Morton, Daniele Amfitheatrof, Ernst Toch, Carl Fortina, George Duning and others. Columbia’s Music Director, Mikhail (“Mischa”) Bakaleinikoff, was the one credited. [22] Universal was one of the few studios to maintain a regular staff of composers into the 1960s. The Music Director was Joseph Gershenson, whose “stable of composers” included Henry Mancini, Frank Skinner and Hans Salter. Possibly in 1957 and certainly by 1958 Vars, too, was writing uncredited cues for Universal. It does not appear, however, that he became one of Gershenson’s regular circle of composers.

Songs and Scores

Vars’ best-known work was for Flipper (1963), produced by Ivan Tors, who followed up that film with Flipper’s New Adventure (1964), and then the television series Flipper (1964 – 68)—all of which used Vars’ music. It was probably his association with this show that lead to his writing the theme music for the first season of the series Daktari, also produced by MGM in the mid-1960s. [23] As we saw earlier in his Polish career, Vars had a gift for composing melodies. In the United States he continued to write popular songs; “Flipper” was probably his most popular piece and was recorded at least eight times between 1963 and 1985. [24]

Vars had other song successes in the U.S. As with many of his earlier hit tunes in Poland, these songs were often introduced in film scores. The lyrics were usually provided by George Ronald Brown or William “By” Dunham. Secondary sources report that Margaret Whiting performed “Over and Over and Over,” and that other singers performing his pieces included Bing Crosby, Doris Day, Brenda Lee and Mel Torme. [25] Many of Vars’ songs came from films—e.g. “Good Love” mentioned earlier, from the film Seven Men From Now (whose alternative title at one time may have been Good Love) was published as sheet music (see Example 3); “Let the Chips Fall (Where They May)” from Man in the Vault, was not only published as sheet music in both English and Italian but also recorded by Jimmy Leyden as a single for Capitol Records. Music from Ski Crazy! was recorded for Electro Vox and the theme from The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come was recorded by the Cambridge Strings for Roulette.

Unsung as he may now be in the United States, Vars’ name is sometimes recognized by horror film specialists. Vars, after all, helped score several “B” grade horror movies including The Leech Woman and, most famously (or infamously, depending on your feelings about the genre), The Unearthly—a film starring John Carradine as a classic mad scientist who creates mutants while performing “unnatural” experiments and hides them in his basement. (This film gained additional notoriety in the early 1990s as one of the films presented on the popular cable television show Mystery Science Theater 3000). Though these scores may not be the music usually studied in more traditional historical musicology, they are worth a look by film music scholars and popular culture specialists.

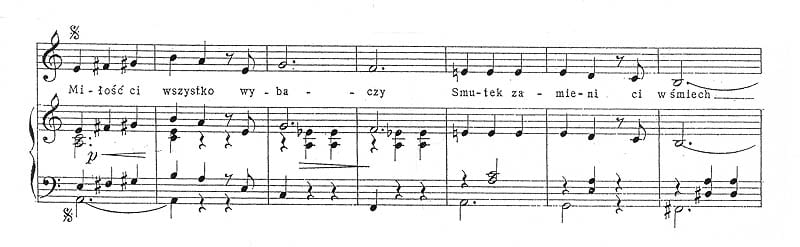

Mrs. Vars has continued to receive requests for permission to use her husband’s songs in various projects. A particularly notable example occurred when Stephen Spielberg used Vars’ song “Mi≥o∂Ê ci wszystko wybaczy” [Love Will Forgive You Everything] in Schindler’s List of 1993 (see Example 4). Part of the film is set in Poland during World War II, and Spielberg’s use of the song is historically accurate. The fact that Vars himself was a Polish Jew who narrowly escaped the fate of the people depicted in the story adds poignancy for the knowledgeable listener.

Within the film the piece works as a powerful dramatic device: we first see an entertainer singing it to a room of German officers, including Schindler himself. Her singing continues in the underscore as the scene cuts to the basement of the building where the sadistic German officer Goeth approaches his Jewish housemaid (a sexual advance is implied). He speaks almost kindly to her as long as the music lasts, but beats her when it stops. Viewers already know he cannot be trusted and therefore the “quiet” time during the song only increases the tension. It remains ambiguous, however, whether the officer’s restraint snaps because the diegetic song ends (implying that, while it lasts, music is able to psychologically “sooth savage beasts”), or whether the song—as a film device—ends to signal Goeth’s attack on the girl, in a not-uncommon conversion from diegetic to non-diegetic music.

Trained in the European art tradition like many of the earlier ÈmigrÈ film composers, Vars was also an active concert hall composer. Though a full bibliography has still to be compiled, these works include: a Sonatina for Orchestra, a Symphony No. 1, a string quartet, a sonata for violin and piano, Preludes for Piano, a piano sonata, a piano concerto, Three Symphonic Poems, the symphonic suite Manhattan Impressions (which is strongly influenced by Gershwin’s concert pieces) and the ballet Maalot.

Vars composed in several very different genres, and exploring how he used this music in his scores could give us further insight into the relationship between popular and classical styles in film. Learning more about Vars’ experience of American jazz in Poland and how he used it in his scores would contribute to our knowledge of jazz, popular American and Polish music, and film music scholarship. The Batjac westerns are another area of potential interest, for they not only provided Vars with solidly respectable American screen credits and were the source of several published songs, they also seem to have been among the most agreeable scoring experiences Vars had in the U.S. It is also becoming clear that in Poland Vars had significant contact with the directors and films of the “Yiddish cinema”—films marketed specifically to Jewish viewers and produced with the participation of actors and sometimes entire casts drawn from the Yiddish/Hebrew theater troupes of Eastern Europe. (I will be discussing this connection in greater detail in an upcoming article.)

Now that a usable filmography is available (see below), together with the beginnings of a list of his other works, Americans will also be able to examine, appreciate and (hopefully) play Vars’ music. Henry Vars was a skilled, active, imaginative, and loved composer—surely it is time to recognize his accomplishments and look again at his work.

IV. Vars’s American Filmography

This filmography, which was first published in the Film Music Society’s Cue Sheet and appears here in updated form, is the most extensive list of Vars’ scores yet available. [28] It is based primarily on ASCAP listings and secondary sources (see the bibliography for a complete list). Few of the these films, however, are readily accessible either on video or in archives and so my personal verification of film credits remains an on-going project.

Vars is the main composer of the scores unless otherwise indicated. The word “cues” indicates that Vars wrote cues for the film, though he was not the only composer involved and may not have received on-screen credit. “Orchestrator” is self-explanatory, as is “assistant” and “co-composer.” Alternative film titles are given in brackets and other miscellaneous information is in parentheses.

This filmography includes several television credits but by no means fully represents Vars work for that medium (e.g. he apparently composed music for the television series Gunsmoke, though the episodes have not yet been identified). The research has yet to done for those scores. Finally, and perhaps needless to say, this filmography is not written in stone—further research may add to or alter it. The author welcomes new information from readers.

1951

- Chained for Life

- Silver City [High Vermillion](cues)1953

- The Big Heat (cues)

- Slaves of Babylon (cues)1954

- Gog (orchestrator)

- The Black Dakotas (cues)1955

- The Phoenix City Story (orchestrator)

- Seminole Uprising (cues)

- Bullet for Joey (orchestrator)

- Ski Crazy!

- Pirates of Tripoli (cues)1956

- Seven Men From Now [Good Love]

- Town On Trial (Vars and Michael Terr, Music Directors)1957

- Gun the Man Down [Arizona Mission]

- Man in the Vault

- The Unearthly [Night of the Monsters, House of the Monsters, working titles] (co-composer with Michael Terr)

- Love Slaves of the Amazons (cues)1958

- Appointment With a Shadow (cues)

- China Doll

- Apache Territory (cues)

- A Stranger in My Arms (cues)

- Girls on the Loose (cues)

- Wild Heritage (cues)1959

- Escort West

- The Leech Woman [Leech] (cues)

- Money, Women and Guns (cues)1960

- Freckles

- The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come1961

- Battle at Bloody Beach [British title: Battle on the Beach]

- The Two Little Bears

- Woman Hunt1962

- Six Black Horses (cues)1963

- Flipper

- House of the Damned

- The Sadist (cues. This attribution is still to be confirmed)1964

- Flipper’s New Adventure [Flipper and the Pirates]

- Flipper (television series, 1964-68)1965

- Deadwood ’76 (cues)1966

- Daktari (television series, 1966 only)

- Valley of Mystery [Stranded] (cues)1970

- Blood Lust (cues)1971

- Fool’s Parade [British title: Dynamite Man from Glory Jail])1993

- Schindler’s List (song only:”Mi≥o∂Ê ci wszystko wybaczy” [Love Will Forgive You Everything])

Notes

[1]. This article incorporates earlier material from my “Henry Vars in Hollywood: A Biography and Filmography” published in the Film Music Society’s Cue Sheet, Vol. 15, no. 4 (October 1999): 3-13. It also develops ideas from talks given at the international conference, “Polish/Jewish Music,” University of Southern California (Los Angeles, November 15, 1998), the annual conference of the Society for American Music (Fort Worth, Texas, March, 1999) and the annual conference of the Film Music Society (Los Angeles, September 17, 1999). As will be seen in the citations below, I am indebted to many people for their help on this project. In particular I want to thank Professor Maja Trochimczyk, Director of the Polish Music Center at the University of Southern California for first suggesting this project as well as providing continuing guidance, materials and encouragement. My thanks also to Mrs. Elizabeth Vars for sharing her memories and materials, and the Special Collections Library (Music Division) of the University of California, Los Angeles. And, as ever, thanks to my husband Edgar Francis IV. [Back]

[2]. See Ryszard Wolanski, “Notes” for Przeboje Henryka Warsa z lat 1927-1939, Intersonus Music, ZAIKS 1994 IS063 Intersonus Music, Warszawa, Al. 3-Maja 2, CD recording. A summary/translation of notes into English by Barbara Milewski of Princeton University was provided by Bert Werb of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. [Back]

[3]. Vars’ sisters were musical: JÛzefina sang at the Warsaw Opera and then moved to Milan and performed at La Scala. Paulina was a pianist. Wolanski, “Notes.” [Back]

[4]. Elizabeth Vars, interview, Oct. 17, 1998. For further information about M≥ynarski, see especially Joseph A. Herter, “A Polish Overture by a British Composer: ‘Polonia,’ Op. 76 by Edward Elgar,” USC Polish Music Reference Center: Newsletter (August 1999), ../news/aug99.html. [Back]

[5]. Mindy Kaye, “Henry Vars (1902-1977),” in Polish Americans in California, 1827-1977, and Who’s Who, edited by Jacek Przygoda (Los Angeles: Polish American Historical Association, California Chapter, Loyola Marymount University, 1978), p. 125. [Back]

[6]. Wolanski, “Notes.” [Back]

[7]. Both Examples 1 (“New York Times”) and 2 (“Dla Ciebie”) were published by Gebethner i Wolff (Warsaw, KrakÛw, Lublin and LÛdz, c1928); these excerpts found in the USC Polish Music Center collection. [Back]

[8]. Wolanski, “Notes.” Also, a list typed by Henry Vars of his Polish film scores (titles translated into English) has 53 titles. Original in the possession of Elizabeth Vars. [Back]

[9]. Elizabeth Vars, interview in person, Oct. 17, 1998. [Back]

[10]. Wolanski, “Notes.” [Back]

[11]. Kaye, “Henry Vars,” p. 125. [Back]

[12]. Wolanski, “Notes.” [Back]

[13]. Elizabeth Vars, interview, Oct. 17, 1998. [Back]

[14]. Wolanski, “Notes.” [Back]

[15]. Kaye, “Henry Vars,” p. 125. [Back]

[16]. See Warren M. Sherk, “The Harry Sukman Collection at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences,” The Cue Sheet, Vol. 6, n1 (Feb. 1989): 30-32. [Back]

[17]. See Allen Eyles, John Wayne, Memorial edition (South Brunswick and New York: A.S. Barnes and Co., 1979), p. 134. [Back]

[18]. “Brog,” “Review of Seven Men From Now,” Variety, Wednesday, July 11, 1956. [Back]

[19]. Anonymous reviewer, “Review of Seven Men From Now,” The Hollywood Reporter, Wednesday, July 11, 1956. [Back]

[20]. Randall Larson has discussed the Music Directors’ responsibilities at Hammer Film Studios—a description that offers a good general overview of the position as well. See Randall D. Larson, Music From the House of Hammer: Music in the Hammer Horror Films, 1950-80, Filmmakers Series No. 47 (Lanham, MD and London: Scarecrow Press, 1996), pp. 5-13. [Back]

[21]. David Raksin, “Holding a Nineteenth Century Pedal at Twentieth Century-Fox” in Film Music 1, 2nd edition, edited by Clifford McCarty (Los Angeles: The Film Music Society, 1998), pp. 167, 171-3. Film music scholar and credits expert Clifford McCarty has told me that to his knowledge, the one exception before 1970 to the practice of crediting only the Music Director was in the film Stagecoach. Winning the Academy Award for musical score in that magical year of 1939, it credited the entire five-man composing team. Phone interview with Clifford McCarty, September 15, 1999. The Stagecoach composers were: Richard Hageman, W. Frank Harling, John Leopold, Leo Shuken, and Louis Gruenberg. [Back]

[22]. My thanks to Clifford McCarty who clarified for me the use of stock and original cues in this film, and to David Schecter for providing me with further valuable information including the names of the composers involved with the film. [Back]

[23]. The theme used after the first season was composed by West Coast drummer Shelly Manne. See Jon Burlingame, TV’s Biggest Hits: The Story of Television Themes from “Dragnet” to “Friends.” (New York: Schirmer Books, 1996), pp. 221-222. [Back]

[24]. For the most complete list of recordings of “Flipper,” see Steve Gelfand, Television Theme Recordings: An Illustrated Discography (Ann Arbor, MI: Popular Culture Ink., 1994). [Back]

[25]. Wolanski, “Notes” and The Lynn Farnol Group, Inc., compilers and editors, The ASCAP Biographical Dictionary of Composers, Authors and Publishers (New York: ASCAP, 1966). Wolanski cites “Over and Over and Over,” sung by Margaret Whiting as Vars’ most popular song, but I have not yet located further information about the piece. [Back]

[26]. Henry Vars, “Good Love” from Good Love [Seven Men From Now]. Los Angeles: Artists Music, Inc., 1956. In the UCLA collection. [Back]

[27]. Henry Vars, “Mi≥o∂Ê ci wszystko wybaczy” [Love Will Forgive You Everything”] from the film Szpieg W Masce. Warsaw, Poland: Gebethner and Wolff-Warsaw, 1933; in the USC Polish Music Center collection. My thanks to Joseph Herter, conductor of the St. John Archdiocesan Cathedral Boychoir of Warsaw, Poland for making a copy of this song available to me. [Back]

[28]. The next most complete list for Vars’ American scores is found in Clifford McCarty, Film Composers in America: A Filmography, 1911-1970, 2nd ed. (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 332. Though I have assembled this list from a number of sources, I depend on McCarty’s dating whenever possible. [Back]

Bibliography

- Burlingame, Jon. TV’s Biggest Hits: The Story of Television Themes from “Dragnet” to “Friends”. New York: Schirmer Books, 1996.

- Eyles, Allen. John Wayne, Memorial edition. South Brunswick and New York: A.S. Barnes and Co., 1979.

- Gelfand, Steve. Television Theme Recordings: An Illustrated Discography. Ann Arbor, MI: Popular Culture Ink., 1994.

- Herter, Joseph. “A Polish Overture by a British Composer: ‘Polonia,” Op. 76 by Edward Elgar.” USC Polish Music Reference Center: Newsletter (August 1999). (../news/aug99.html).

- Harris, Steve. Film and Television Composers: An International Discography, 1920-1989. Jefferson, N.C. and London: McFarland and Co., 1992.

- Harris, Steve. Film, Television and Stage Music on Phonograph Records: A Discography. Jefferson, N.C. and London: McFarland, 1988.

- Mindy Kaye, “Henry Vars (1902-1977).” Polish Americans in California, 1827-1977, and Who’s Who. Ed. Jacek Przygoda. Los Angeles: Polish American Historical Association, California Chapter, Loyola Marymount University, 1978.

- Larson, Randall D. Music From the House of Hammer: Music in the Hammer Horror Films, 1950-80, Filmmakers Series No. 47. Lanham, MD and London: Scarecrow Press, 1996.

- The Lynn Farnol Group, Inc., compilers and editors. The ASCAP Biographical Dictionary of Composers, Authors and Publishers. New York: ASCAP, 1966.

- McCarty, Clifford. Phone conversation, September 15, 1999.

- Raksin, David. “Holding a Nineteenth Century Pedal at Twentieth Century-Fox” in Film Music 1, 2nd edition. Ed. Clifford McCarty. Los Angeles: The Film Music Society, 1998.

- Schubert, Linda. “Henry Vars in Hollywood: A Biography and Filmography.” The Cue Sheet: The Journal of the Film Music Society. Vol. 15, n4 (Oct. 1999): 3-13. (Distributed in October, 2001).

- Sherk, Warren M. “The Harry Sukman Collection at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences,” The Cue Sheet: The Journal of the Film Music Society. Vol. 6, n1 (Feb. 1989) 30-32.

- Wolanski, Ryszard, “Notes.” Przeboje Henryka Warsa z lat 1927-1939. Intersonus Music Label. ZAIKS 1994 IS063 Intersonus Music; Warszawa, Al. 3-Maja 2. CD recording.

- Vars, Mrs. Elizabeth. Interviews, September 15, 1998 (phone), October 17, 1998 (in person), Sept. 5, 2000 (in person).

Music by Henry Vars

- Vars, Henry. “Dla Ciebie” [For you]. Warsaw, Kraków, Lublin and Łódź: Gebethner i Wolff, 1928. USC Polish Music Center collection.

- _________. “Good Love” from Good Love [Seven Men From Now]. Los Angeles: Artists Music, Inc., 1956. UCLA collection.

- _________. “Let the Chips Fall (Where They May)” from Man in the Vault. New York: Bregman, Vocco and Conn Inc., 1956. UCLA collection.

- _________. “Miłość ci wszystko wybaczy” [Love Will Forgive You Everything] from Szpieg W Masce [A masked spy]. Warsaw, Poland: Gebethner and Wolff-Warsaw, 1933. USC Polish Music Center collection.

- _________. “New York Times.” Kraków, Lublin and Łódź: Gebethner i Wolff, c1928. USC Polish Music Center collection.

- _________. “Theme from ‘Daktari’.” New York: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc., 1966. UCLA collection.

- _________. “Vada Il Mondo Come Va (Let the Chips Fall)” from Man in the Vault. Milan: Edizioni Musicali; New York: Bregman, Vocco and Conn Inc., 1956. UCLA collection.

Sources for Filmography

- ACE on the web. www.ascap.com/ace/ACE.html.

- Internet Movie Database. http://us.imdb.com/search.

- Limbacher, James, compiler and editor. Film Music: From Violins to Video. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1974.

- Limbacher, James L. and Wright, H. Stephen. Keeping Score: Film and Television Music, 1980-90 (with additional coverage of 1921-79). Metuchen, N.J. and London: Scarecrow Press(?), 1991.

- The Lynn Farnol Group, Inc., compilers and editors. The ASCAP Biographical Dictionary of Composers, Authors and Publishers. New York: ASCAP, 1966.

- McCarty, Clifford. Film Composers in America: A Filmography, 1911-1970, 2nd ed. (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 332

- Schecter, David. Phone conversation, November 6, 1999; email correspondence.

- TV Gen TV Guide Entertainment Network. http://www.tvgen.com/index.sml [referred to as TVGEN].

- Vars, Henry. Typed list of all Polish film scores, with titles translated into English. Elizabeth Vars Private Collection, Los Angeles, n.d.

Linda Schubert is an independent scholar, writer and editor living in Los Angeles. She received her Ph.D. in musicology from the University of Michigan (1994) with a dissertation on film music, entitled Soundtracking the Past: Early Music and its Representations in Selected History Films. Schubert is particularly interested in music used in period films and how these films aurally construct the past. She is also interested in helping identify and bring into musicological discussion unique film scoring practices such as team composing and the re-use of cues in multiple films. She has published and presented papers in the U.S. and abroad on these subjects. Formerly a reviewer of classical music websites for the internet magazine BRIEFME.COM, Schubert has contributed several review-essays to the forthcoming Film Music Journal. She is Book Reviews Editor and a member of the Editorial Board of that publication, as well as an editorial assistant for the Polish Music Journal and the Polish Music History Series. She also serves as Music Director for the Chaplaincy, Canterbury Westwood Foundation (Episcopal student ministries).

Schubert first began to work with the film scores of Henry Vars at the suggestion of Prof. Maja Trochimczyk, Director of the Polish Music Center at USC for the international conference “Polish/Jewish Music!” held at USC in the fall of 1998. She has also presented papers about Vars for the American Music Society and the Film Music Society. The paper published here in the Polish Music Journal is a revised and greatly expanded version of an article that first appeared in the Film Music Society’s Cue Sheet.