by Maja Trochimczyk

Abstract

Public fascination with Polish composer, virtuoso pianist and statesman, Ignacy Jan Paderewski, continued throughout his creative life. His museum in Morges, Switzerland, his Archives at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland and at the Archiwum Akt Nowych in Warsaw, contain numerous gifts, honors, tributes, and awards, bestowed upon Paderewski during his lifetime. This paper presents a range of literary tributes to the pianist-politician, spanning his career, from 1889, following his first international triumphs as a virtuoso in Paris and Brussels, to 1941 and elegies that expressed grief after his death. The overview includes analysis and context of Paderewski-themed poems by Richard Watson Gilder, John Huston Finley, Robert Underwood Johnson, Charles Phillips, Henryk Merzbach, Julian A. Święcicki, Maryla Wolska, Waldemar Bakalarski, and Anne Strakacz-Appleton.

Several thematic threads are singled out and exemplified by poems: “synaesthetic,” “erudite,” “patriotic,” “laudatory” or “commemorative,” and “elegiac.” The poetic responses, arising as a reaction to current political and artistic events, feature two turning points (a) in 1918 when Poland regained independence and Paderewski became its prime minister and (b) in 1941 when he died. While the literary quality of most of these poems is not consistent, the poetry provides a valuable document of its times and a testimony to Paderewski’s close links with the members of the American literary establishment (Gilder and Finley were editors of important journals and influential men of letters; Finley and Phillips taught at universities, etc.). The poems also reveal the virtuoso pianist’s unique role in Polish culture, both within the country and in exile communities. The text of Paderewski’s patriotic song of 1917 is also discussed; all the poems are collected in an appendix.

Article

I. Poetry of Music and Patriotism

Poetry is just one of the ways in which the intense public fascination with “the immortal”[1] pianist-composer-statesman, Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860-1941) was expressed during his lifetime. Since his triumphant entry onto the international music stage, Paderewski was the subject of poems, often florid or erudite, always enthusiastic. The “Paderewski-themed” poetry highlights its authors’ responses to various aspects of their subject’s multi-faceted career—the pianistic virtuosity, the compositional talent, and the patriotic zeal. This paper will examine the range of these responses and the image of Paderewski that was constructed in selected works by American and Polish poets, including verses by: Waldemar Bakalarski (a poem of 1941); John H. Finley (1863-1940; poems of 1914 and 1928); Richard Watson Gilder (1844-1909, poem of 1906); Robert Underwood Johnson (1853-1937, poem of 1916); Henryk Merzbach (poem of 1888); Charles Phillips (1880-1933, poem of 1928); Julian Adolf Święcicki (poem of 1899); and Marian Gawalewicz with Maryla Wolska (1873-1930; poem of 1899). Of the American writers, only the names of Gilder and Phillips appear in Paderewski biographies; the former—as a personal friend and supporter, the latter—as a biographer.

An overview of the Paderewski-themed poetry (the list of currently known poems, including their sources, is enclosed in Appendix I) highlights two transformations of the subject matter, after 1918 and after 1941, as well as characteristic differences between the images of the great virtuoso presented in Poland and in the U.S. The first turning point marks the time of Poland’s rebirth after World War I when the country regained independence following a period of over 120 years when it was divided between Russia, Prussia, and Austria. It was universally believed this event would not have been possible without the efforts of Paderewski.[2] Simultaneously, this historical moment marks the end of Paderewski’s career as a composer: his last work, a patriotic anthem “Hej, orle biały! [Hey, white eagle] was written as the hymn of the Polish Army in the U.S. in 1917. The text of this hymn, penned by Paderewski, is enclosed in Appendix II. The second, more obvious, milestone in Paderewski’s poetic reception marks the event of his death, which was commemorated in a series of elegies by his compatriots.

Before Paderewski’s intense involvement in the patriotic campaign on Poland’s behalf in the U.S. (1915-1918), ending with the historical event of the country’s sovereignty in 1918, poems about him followed three thematic paths: (1) “synaesthetic responses,” i.e. attempts to capture in elaborate verbal imagery the fleeting impressions of Paderewski’s musical performances (represented by a poem by Richard Watson Gilder), (2) “erudite responses,” i.e. venerations of Paderewski’s musical genius cast in classical terms, with complex references to Greek antiquity (poems by John H. Finley), and (3) “patriotic responses” connecting Paderewski to Polish musical traditions, expressing his role in Polish culture as a “new Chopin,” or an internationally recognized “Master” whose art could raise awareness of Polish history and culture, with the expected result of assisting Poland in its resurrection as an independent state. The third approach connected Paderewski to his musical roots in the achievements of Poland’s greatest pianist-composer, Fryderyk Chopin, but simultaneously transformed the artistic goals of composing and performing music into a patriotic mission (poems by Święcicki, Merzbach, and Wolska).

After Poland became an independent country and during the period of Paderewski’s increased political prominence in the 1910s and 1920s, numerous laudatory verses appeared, praising the musician as a voice of the nation in elaborate linguistic constructions linking sound, music, patriotism, etc. These poems form a category of politically-oriented (4) “commemorative” or “laudatory responses”, praising Paderewski’s musical talent in general terms, while emphasizing his dedication to the national cause (including poems by Finley, Johnson, and Phillips). In that period, I have not found additional testimonies to the electrifying power of Paderewski charisma at the piano expressed so eloquently as in Gilder’s earlier verse. A 1934 poem, “Immortal Jan Ignace Paderewski”, might be an exception, but its text was not available for the present study.[3] This paucity of “synaesthetic” descriptions of the music’s impact on its listeners in the inter-war period indicates a change in the tone of public response to Paderewski’s persona and the nature of his appearances. This transformation was even more profound after his death—an event to which his Polish compatriots reacted with sorrow in (5) “elegiac responses,” i.e. farewells to a great musician-statesman whose art was seen as primarily serving patriotic purposes. Two examples of such mourning poetry by Poles and Polish emigrants are listed below, neither one of particularly hight artistic merit (by Bakalarski and Strakacz-Appleton).

II. Paderewski’s Triumphs and Patriotic Hopes

Paderewski’s first international triumphs took place in Paris in the spring of 1888.[4] After the enthusiastic reception of his performances there, he traveled to Belgium, where—invited by Francois-Auguste Gevaert, the director of the Brussels Conservatory—he gave a concert on 14 April 1888. He returned to Brussels in December 1888 for three concerts; at that time, the Polish expatriates in Belgium honored his successes with a reception in a private home. The event included a performance by Paderewski and violinist Józef Wieniawski. On the same occasion, the vice-president of the Polish Charitable Society in Brussels [Polskie Towarzystwo Dobroczynności], Henryk Merzbach, a writer and editor, recited the following poem that he wrote for Paderewski:[5]

Płyń, młody mistrzu, po tym oceanie

Burz, namiętności, rozkoszy i chwały…

Graj nam a naród niech zmartwychwstanie

Choćby na chwilę, wierząc w ideały…

Twa gra nas brata z niebem i z krajem,

Przyjm więc serdeczne nasze uwielbienie.

Świat da ci sławę, my ci serce dajem

Nowy Chopinie.

Translation:

Sail, o young master, on this ocean

Of storms, passions, delights and glory…

Play for us and let the nation resurrect

if only for a moment, believing in ideals…

Your music unites us with heaven and with our country,

So please accept our heartfelt worship.

The world will give you fame, we give you our heart –

you, new Chopin.

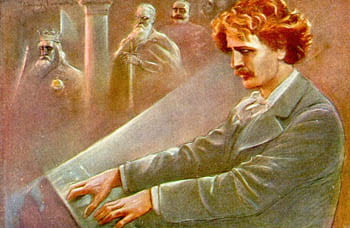

This poem, published in Poland in Dziennik Poznański (no. 289 of 16 December 1889), set the tone for the Polish reception of Paderewski, mixing hopes for the nation’s resurrection with praise for the “young master”, who had inherited the prophetic gifts of Chopin. The nation’s resurrection mentioned by Merzbach finds a visual expression in a postcard from the late 19th century, issued by Wydawnictwo Salonu Malarzy [The Publishers of the Salon of Painters] in Kraków (see Figure 1). In this image, a series of ghosts of the Polish kings arise from the mysterious mist surrounding Paderewski playing the piano while a supernatural light emanates from the instrument.

Postcard, Wydawnictwo Salonu Malarzy Polskich, Kraków, n.d. (late 19th c.)

Maja Trochimczyk Private Collection, Los Angeles.

The virtuoso spent the following two years on concert tours in Europe, taking him from Paris, to Vienna, London, Budapeszt, and back to Brussels.[6] On 3 March 1891 he gave a recital for the “Cercle artistique et littéraire” with eleven pieces on the program: Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 111, Schubert’s Impromptu in A-flat Op. 142 no. 2 and a Minuet; Liszt’s arrangement of Schubert’s Lied Erlkonig; Chopin’s Ballade in F-major Op. 38, a Mazurka, and Polonaise in B-flat major Op. 71 no. 2; Anton Rubinstein’s Barcarolle Op. 93; his own Humoresques de concert Op. 14; and Liszt’s unspecified Hungarian Rhapsody. In gratitude, a group of Poles from Brussels signed the following poem dedicated to Paderewski and presented it to him on 5 March 1891:[7]

Paderewskiemu

Znowu do nas powracasz, poeto muzyki,

Tak wracają na wiosnę słońce i słowiki.

Skromne nasze tułacze i biedne poddasze,

Lecz dajem Ci, co mamy—tęskne serca nasze.

Translation:

Again you return to us, you, the poet of music,

As the sun and the nightingales return in the spring.

Modest and poor is our place of exile [lit. “homeless garret”],

But we give you what we have—our longing hearts.

While not more than a florid greeting, this short poem expresses the hopes that Poles attached to Paderewski as a fellow compatriot, a living connection to their homeland, and a possible harbinger of Poland’s freedom.

After triumphant tours in Europe and the U.S. and thirteen years of absence from his native country, Paderewski returned to Warsaw for a series of concerts held in the winter of 1899. The concerts were characterized by an intense fascination with an artist who rose to international prominence abroad. Musical events were interspersed with various honorary celebrations, award dinners, and tributes. A dinner held on 15 of January 1899 in Warsaw had a most distinguished list of participants.[8] The guests of honor included Poland’s most famous novelist, Henryk Sienkiewicz and the founder of the Warsaw Philharmonic, industrialist Leopold Kronenberg.[9] Paderewski was seated between them, with a watercolor by Stanisław Lentz marking his place at the table. The image portrayed the virtuoso at the piano from which the spirit of Chopin was emerging—thus expressing, in a tangible form, the vision of Paderewski as a “new Chopin” articulated earlier by Merzbach. The proceedings opened with a recitation of another “Paderewski” poem, written by Julian Adolf Święcicki (a poet of little distinction in Polish literary history). The text was later published in the album, Ignacemu Janowi Paderewskiemu. Album Podpisów preserved in Paderewski Archives in Archiwum Akt Nowych in Warsaw.[10] Besides the poem, the album included signatures and greetings of the most eminent members of the Polish cultural milieu including: writer Aleksander Głowacki (Bolesław Prus); playwright Lucjan Rydel; conductor-composer Emil Młynarski; composer Zygmunt Noskowski; music historian Aleksander Poliński; music historian Ferdynand Hoesick; and music lover and philanthropist Aleksander Rajchman (co-founder of the Warsaw Philharmonic). Święcicki’s poem, though hardly a memorable work of art, expressed sentiments felt by many Poles upon Paderewski’s return to his homeland:

Wyleciałeś jako orle z gniazda

młodych skrzydeł doświadczyć potęgi […]

Nie dlatego w świat biegłeś wytrwale,

By żyć orgią i kąpać się w szale […]

By z wędrowki mozolnej a długiej

Przynieść Polsce swój wieniec zasługi […]

I już jasność Twej gwiazdy nie skona,

Bo ojczyzna Twą sławą… wsławiona.

Translation:

You flew out as an eaglet from the nest

To experience the power of young wings […]

You did not ceaselessly travel round the world [lit. “run persistently”]

To live in orgies and bathe in ecstasies […]

Yet you went on a long and arduous journey,

to bring back, for Poland, your wreath of honor […]

Now the brightness of your star will not die,

Because your homeland is made famous through your fame.

The mention of “orgies” and “ecstasies” is a reference to the eccentric interests of Young Poland luminaries, the symbolist writer Stanisław Przybyszewski (preoccupied with intense spirituality and emotionalism, the demonic world, eroticism and self-expression) and the painter Władysław Podkowiński (1866-1895), whose monumental and borderline-kitschy painting “Szał uniesień” [The Frenzy of Ecstasy] was displayed amidst great public controversy in 1894.[11] The painting depicted a raving, naked woman riding a huge, wild black horse through tumultous blackness. In a fit of rage, Podkowinski tried to destroy this painting during its exhibition; a year later, in 1895 he committed suicide leaving on his canvas a bleak interpretation of Chopin’s Funeral March from his Sonata in B-flat minor. No doubt, Poles were relieved that Paderewski, in contrast to his wildly bohemian compatriots such as Podkowiński, traveled around the world without similar artistic excesses, focusing instead on musical excellence and increasing the international stature of his country. His personal, artistic and financial achievements were seen as successes of the whole nation, both in Poland and among Polish émigrés in the countries that he visited. A Warsaw daily, Kurier Warszawski was supposed to publish Święcicki’s poem, but it was censored by the Russian authorities to such an extent that the cuts deeply changed its meaning. As a result, the poem’s publication was postponed for twenty years: it was issued in no. 15 of 15 January 1919, two months after Poland regained independence (11 November 1918) and a day before Paderewski started his official duties as Poland’s first prime minister, or “president of the council of ministers” (hence his subsequent honorific title of “Mr. President”).

Another poem, also dating from the period of Paderewski’s triumphant return to Poland in January 1899, was published in no. 19 of Kurier Warszawski, on 19 January 1919, i.e. three days after Paderewski was inaugurated into office. In the poem, entitled simply Paderewski, odd strophes were penned by a little-known poet Marian Gawalewicz and even-numbered strophes were written by a well-respected lyrical poet of the Young Poland movement, Maryla Wolska (1873-1930).[12] Paderewski’s biographer, Andrzej Piber, cites the following example of Wolska’s contribution:[13]

Pożar nad czołem, a w oczach mgła

Mistyczne cienie kładła.

Przed nim elegia smutna szła

I tęsknych mar widziadła…

Za nim się snuł marzący tłum,

Melodią wniebowzięty,

I szedł za czarem jego dum

Przez dźwięcznych fal odmęty…

I szedł za czarem jego słów,

Zaklętych w tony rzewne

I wołał w głos: “O, graj! O, mów!”

I śpiącą wskrześ królewnę!”

Translation:

The fire above his forehead and the mist in his eyes

Spread out the mystic shadows.

Before him a sorrowful elegy walked

And phantoms of lonesome spirits…

Behind him wandered a dreamy crowd

Transfixed with heavenly melodies,

Thus they followed the charm of his song

Through the depths of sonorous waves…

Thus they followed the charm of his words,

Spellbound into longing tones

Thus they called out loud: “Oh, play!, Oh, speak!”

And resurrect the sleeping princess!”

Again we encounter an image of mystical mists and sorrowful spirits that could be (and were) read as references to the legendary past of Poland’s greatness, a nation now awaiting its rebirth into a sovereign country. Thinly veiled allusions to national matters in Wolska’s poem include also the image of the “sleeping princess” —borrowed from such classic fairy-tales as “Sleeping Beauty” by Charles Perrault (1696) or “Snow White” by the Brothers Grimm (1812).[14] Both fairy-tale maidens were saved from their death-sleep by courageous princes; in Perrault’s story this deadly slumber lasted over a hundred years—hence the parallel to Poland’s enforced “sleep” while the country waited for the return of its freedom. Paderewski, cast in the role of his country’s lover and savior, was to “resurrect” the Polish princess, thus performing a task usually assigned to God himself (but realized by the “prince charming” in the fairy-tales). This elevation of a musician and composer to the realm of legends and tales is a common thread in subsequent Paderewski-themed poems.

Simultaneously the idea of Poland being asleep while waiting for its resurrection was widespread at the end of the 19th century. A Polish folk tale from that period described a legend of the sleeping knights, who—hidden in the caves in the Tatra Mountains—for a hundred years waited for the call to arms that would wake them from their dreams.[15] The postcard included below (see Figure 2) presents another version of this patriotic slumber: the sleeping knight ready for combat, in full armor and with national colors is guarded by an angel who would, hopefully, awake him at the time of struggle. The image, probably created by Maksymilian Piotrowski (1813-1875), an artist whose patriotic paintings depicted Polish legends and events from the country’s history, was published in Galicia at the end of the 19th century.[16] The image could have been created after the fall of the January Insurrection (1863), the last, violent attempt at regaining Poland’s liberty.

III. Gilder and Musical Symbolism

Outside his native country, Paderewski’s poetic reception was not limited to occasional tributes filled with praise and expressions of national hope. His tours of America resulted in several poems of distinct artistic quality written by Richard Watson Gilder, John H. Finley, Robert Underwood Johnson, and Charles Phillips. These names are not well known to Polish music scholars and Finley and Johnson do not appear in Paderewski biographies. Gilder is mentioned as the composer’s associate and personal friend in Andrzej Piber’s study of Paderewski’s early years and in Adam Zamoyski’s biography, both of 1982. Phillips is referred to solely as Paderewski’s biographer.

According to Andrzej Piber, Paderewski’s contacts with Richard Watson Gilder (1844-1909) resulted from the latter’s long-lasting friendship with the Polish actress Helena Modrzejewska (known in the U.S. as Modjeska).[17] Adam Zamoyski writes that the Polish pianist soon became a good friend of the poet, considering Gilder’s house to be his “real home during those first years in America.”[18] In Gilder’s home Paderewski had the opportunity to meet Mark Twain and Andrew Carnegie, among other members of American society, but the contacts between the two men were not limited to socializing. In the 1890s Gilder served as the secretary of the Washington Arch Committee gathering funds for this monument; he probably approached Paderewski to ask for donations. According to Andrzej Piber, the pianist decided to designate to this purpose all the income from the final concert of his first, triumphant tour of the U.S. (1891-1892). The fundraiser was held at the Metropolitan Opera on 28 March 1982 with the participation of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The event included, besides the music (i.e. piano concerti in A minor by Schumann and Paderewski, as well as a solo Hungarian Rhapsody by Liszt), a special ceremony during which Gilder and Parker Goodwin, members of the Washington Arch Committee, offered Paderewski a wreath in national colors of both nations. On the same day, the Washington Arch Committee passed a resolution thanking Paderewski for the greatest individual contribution to the fund ($4300). Gilder was a co-signer of this declaration that also bestowed upon Paderewski a gift of two national flags that were used to decorate the hall during the concert.

This footnote to Polish-American friendship appears in an entirely different light upon realizing that its protagonist, Richard Watson Gilder, published numerous volumes of poetry and that many of his poems dealt with other arts, painting, acting, and music. He wrote about actresses Helena Modjeska and Eleonora Duse, composers Beethoven and Chopin, MacDowell and Paderewski.[19] A volume of poetry about music, A Book of Music, was published in 1906; drafts of the poems are held in the Gilder Collection at Princeton Library.[20]

It is clear, just from the range of his artistic subjects, that Gilder’s response to art was of a synaesthetic nature; he attempted to find connection between colors and sounds, shapes and emotions. Such inter-penetration of multi-sensory experiences is present, for instance, in his definition of the sonnet:

The Sonnet (In Answer to a Question)

What is a sonnet? ‘T is the pearly shell

That murmurs of the far-off murmuring sea;

A precious jewel carved most curiously;

It is a little picture—painted well.

What is a sonnet? ‘Tis the tear that fell

From a great poet’s hidden ecstasy;

A two-edged sword, a star, a song—ah me!

Sometimes a heavy-tolling funeral bell.

This was the flame that shook with Dante’s breath;

The solemn organ whereon Milton played,

And the clear glass where Shakespeare’s shadow falls:

A sea this is—beware who ventureth!

For like a fjord the narrow floor is laid

Deep as mid-ocean to the sheer mountain walls.

Gilder believed in poetry’s capabilities to express hidden emotions and impressions of its author in a perfectly crafted form; as a poet he is associated with the “genteel” tradition, the representatives of which avoided erotic or stark subjects, attempting to edify rather than shock and bewilder their readers. Music, the “wordless art,” is a poet’s supreme challenge. Verses that Gilder penned about Paderewski, after having ample opportunities to hear him in public concert halls and at home, reveal the depth of synaesthetic links in his response to music:[21]

How Paderewski Plays

If words were perfume, color, wild desire

If poet’s song were fire

That burned to blood in purple-pulsing veins;

If with a bird-like trill the moments throbbed to hours;

If summer’s rains

Turned drop by drop to shy, sweet, maiden flowers;

[…]

If melody were tears and tears were starry gleams

That shone in evening’s amethystine dreams;

Ah, yes, if notes were stars, each star a different hue,

Trembling to earth in dew;

Or, of the boreal pulsings, rose and white,

Made majestic music in the night;

If all the orbs lost in the light of day

In the deep silent blue began their harps to play;

[…]

If ever art could image (as were the poet’s duty)

The grieving, and the rapture, and the thunder

Of that keen hour of wonder,

That light as if of heaven, that blackness as of hell, –

How Paderewski Plays then might I dare to tell.

Gilder’s poem about Paderewski’s talent as a performer belongs in a cycle of his works celebrating great musicians. In this extended simile the poet brings up a range of synaesthetic comparisons of music with natural phenomena and surreal, enchanting imagery. The poem is sophisticated and richly associative, filled with imagery of nature’s power and beauty, from cosmic orbs to dew drops, from storm-clouds to eclipse and aurora borealis. The complete verse includes no less than eighteen “ifs” comparing Paderewski’s art with natural wonders and emotional states: mortal woe, tears, rapture… The romantic intensity of this poem is well balanced with its elaborate form. Irregular phrase length piques the interest of listeners or readers awaiting the unexpected resolution; the poem seems written to be read aloud or recited. Paderewski’s musical gifts, according to Gilder, reach beyond the realm of natural forces and human comprehension.

IV. Finley and Classical Erudition

A different approach to praising Paderewski’s musical talents was taken by John Huston Finley (1863-1940).[22] He wrote two poems for the Polish pianist, separated by over a decade and expressing different concerns. Both poems, though, betray Finley’s life-long preoccupation with classical antiquity and a modern revival of Greek culture. Finley was a professor, writer, and editor of enormous influence on early 20th-century America.[23] With a broad array of interests, ranging from the classics, through modern poetry, American history and politics, Finley was highly successful as a college professor (at Princeton University) and president (at City College of New York, until 1913). The following decade saw him as an administrator, i.e. the Commissioner of Education of the State of New York (until 1921). After resigning from that post, Finley became an associate editor, and then in 1937, the editor-in-chief of the New York Times. During his distinguished career, Finley engaged in a large array of charitable activities, working for the Boy Scouts of America, the Commission for the Blind, the Red Cross in Palestine, and the American Biography project (sponsored by the American Council of Learned Societies). He received thirty-two honorary doctorates from the U.S. and Canada. Finley believed that the study of Greek and Latin provided the best foundation for liberal education, and that good education improved society and increased the personal quality of life. His interests in Greek antiquity extended beyond books—he was one of the leaders in the project of reconstructing the Parthenon in Athens. His list of publications contains a range of titles that speak for themselves:[24]

- The French in the Heart of America (New York, C. Scribner’s Sons, 1915);

- Our Need of the Classics (Princeton?, 1919);

- American Democracy from Washington to Wilson: Addresses and State Papers with James Sullivan (New York : Macmillan Co., 1919);

- Duties of Schools When the Nation is at War (New York: National Security League, 1918);

- The Guide to Literature (Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday, Page and Company, 1926);

- The University Library in 24 volumes, co-edited with Nella Braddy, and Christopher Morley (Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday, Page and Co., 1927).

Finley’s fascination with ancient Greece is clearly noticeable in his poem written after Paderewski’s performance in the town of Troy, New York on 27 March 1914. This concert was part of an extended tour through the Eastern states that lasted from 14 March to 22 April 1914 and ended with Paderewski’s return to Europe in May that year. The tour alternated between two programs, one with Paderewski’s Piano Concerto in A-minor and another with a range of solo works. [25] Paderewski performed the concerto: in Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, Baltimore, New York, Brooklyn, Providence, R. I., and Chicago. The solo recital consisted of the following compositions:

- Liszt’s arrangement of J. S. Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in A minor;

- Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 27 no. 2 in C-sharp minor;

- Schumann’s Fantasiestucke Op. 12;

- Liszt’s arrangements of Schubert’s Erlkonig and Soirées de Vienne in A major;

- Chopin’s Ballade in A-flat major Op. 47;

- Chopin’s Nocturne in B major Op. 62 no. 1;

- Chopin’s Polonaise in A-flat major Op. 53;

- Liszt’s arrangement of Wagner’s Isoldes Liebestod; and

- Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody (not numbered).

This mammoth program was repeated in Newark, N. J.; Troy, N. Y.; Harrisburg, Pa.; Hartford, Conn.; Rochester, N. Y.; Erie, Pa.; Kansas City, Mo.; and Wells-Bijou Theatre in an unknown location (on 22 April, the last concert of the tour). Paderewski had earlier presented the same set of pieces minus the opening Liszt-Bach arrangement at a concert in Madison, Wisconsin, on 13 December 1913, and also during a tour of the West in January 1914 (in Colorado Springs; Boise City, Idaho; and Vancouver, Canada).

While attempting to capture the musical qualities and emotional impact of this concert, Finley decided—instead of describing the music and its effects on the listener, as Gilder would have done—to elevate Paderewski to the realm of mythical heroes by comparing him with the Greeks and Trojans from Homer’s Illiad. Undoubtedly, the town’s name, “Troy,” inspired this ode to the ancient greatness and its modern reincarnation in Paderewski. Finley wrote:[26]

Beside Scamander’s stream in ancient Ilium[27]

(From whose dim, moon-lit ramparts Troilus

Sighed toward the Grecian tents where Cressid lay)

Brave Hector, so ’tis said, derided him

Whose love for Helen gave to Homer’s harp

The timeless Iliad: “O brother mine

The sounding lyre shall not avail thee now!”

The protagonists of Homer’s epic include two arguing brothers, sons of Priam, the king of Troy: the warrior, mighty Hector and the beautiful and charming musician, Paris, who seduced Helene and, by doing so started the Trojan wars. If not Paris but Paderewski had been there, with his vastly superior instrument (the piano invented by Christofori), the Trojan wars would have ended quite differently—or so claims Finley:

I heard brave Hector’s taunt again, and then

I heard reply: “Great Paderewski played

Not such a puny lyre as Paris twanged,

But one Christofori designed to sound

The thundering of battle, and, alike,

The peaceful breathings of an oaten pipe;

And hearing, thought: Had this Red Polack stood

Beside old Priam on the Trojan walls

The battle lost immortally were won!”

The poem is a game of sophistication and erudition; Finley’s allusions include the names of Christofori, the Italian inventor of the piano, and of Andrew Lang (1844-1912), the venerated English translator of the Illiad.[28] Without a thorough knowledge of the ancient epic, its heroes, stories, and locations, Finley’s narrative, effectively replacing Paris with Paderewski and reversing the course of the whole Trojan war, would be incomprehensible. The poet’s choice of substituting one musical seducer with another one—adored for his physical beauty (including startlingly “red” or “golden” hair) and personal charisma as much as for his musical talents [29] – reveals his erudition and insight. It is not only the power of sound emitted by a better instrument that gave Paderewski an advantage over his ancient predecessor, though obviously the dynamic range of the grand piano far exceeds that of the ancient lyre or kythara.[30] It is also the strength of Paderewski’s musical talents apparent in the choice and scope of his concert program, lasting well over three hours, that gave him an advantage over his mythological counterpart, i.e. Paris, and his adversary, i.e. the Greek attacker of Troy, Achilles.

Thus, in Finley’s poem Paderewski entered mythology and became an “immortal.” The American author wrote another poem about the Polish pianist in 1928, again drawing a metaphor from the rich treasury of Greek mythology. Finley read this poem as a part of his speech during the ceremonial dinner celebrating Paderewski’s role in the regaining of Poland’s sovereignty on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of this event. The dinner, organized by the Kosciuszko Foundation, was commemorated with a book of tributes and greetings to Paderewski, including several poems. Finley’s text appeared on the first page of this collection; his speech including the whole poem is reprinted in Part II of “Paderewski and the Tenth Anniversary of Poland’s Independence” in the current issue of the Journal.

In the 1928 poem, Finley compared Paderewski to a demi-god, Orpheus, attempting to bring back from Hades his wife, Euridice, who had died and whose spirit was imprisoned in the Underworld. Orpheus failed despite the magic of his music that enchanted the guardians of Hades and allowed Euridice to pass; he failed because of a lack of self-restraint, or loving her too intently, or having too much curiosity… Explanations of the immensely popular Orpheus myth differ. Nonetheless, it is clear, to Finley at least, that Paderewski succeeded in the quest for his Euridice:

You’ve brought from out the air such symphonies

As God with all His earth-orchestral range

From cataract through soughing wind to lark

Could not produce without the skill of man.

[…] As ancient Orpheus trod the aisles of hell

To rescue from its thrall Eurydice,

So you for Poland. But though Orpheus failed

You won. Polonia Restituta lives.

In Latin, “Polonia Restituta” means “rebuilt” or “restored” Poland; it is also the name of the new country’s most important state honor, awarded to individuals that assisted the country on its way to freedom. The name of this distinction was well-known to those present at the New York ceremony where the poem was presented in public: several holders of “Polonia Restituta” medals were in the audience, including Charles Phillips and Zygmunt Stojowski. Therefore, Finley’s casual use of this Latin phrase did not require extraordinary sophistication of his listeners; neither was the use of the myth of Orpheus-Paderewski and Euridice-Poland as complex and unintelligible as the references to the epic of Illiad had been in the earlier poem.

While still recognizing the significance of Paderewski’s musical achievements and praising them in extraordinary similes, Finley described Paderewski’s political actions as constituting the most important achievement of his life. Apparently, not much could compare with restoring a country to the political map of Europe. Besides Orpheus and Euridice, the poem also mentions two illustrious Poles—the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, and the hero of the American Revolutionary War as well as a fighter for Poland’s independence, general Tadeusz Kosciuszko. The appearances of the names of these two men whose actions profoundly changed the world is not accidental. By shifting attention from the musical to the political, the poet articulated a hierarchy of human achievements described later by Hannah Arendt in The Human Condition.[31]

According to the philosopher, whose views were influenced by the bitter experiences of World War II, the Holocaust, and a personal confrontation with totalitarianism, “action” takes precedence over “contemplation,” or “labor,” or “production” as the most worthy form of human behavior. Arendt described her ideal of a politicized “Vita Activa,” pursued by free, fully individualized subjects in the “agora” of a public space. This active life contrasted with the lives of the physically productive “Homo Faber” and the merely hard-working “Animal Laborans.” As Arendt wrote:[32]

With word and deed we insert ourselves into the human world, and this insertion is like a second birth, in which we confirm and take upon ourselves the naked fact of our original physical appearance. […] To act, in its most general sense, means to take an initiative, to begin (as the Greek word archein, “to begin,” “to lead,” and eventually, “to rule,” indicates), to set something into motion (which is the original meaning of the Latin agere). In acting and speaking, men show who they are, reveal actively their unique personal identities and thus make their appearance in the human world. […] The political realm rises directly out of acting together, the “sharing of words and deeds.” Thus action not only has the most intimate relationship to the public part of the world common to us all, but is the one activity which constitutes it.

It is perhaps not a coincidence that Arendt’s theory arose from her study of ancient philosophers and that Finley was so thoroughly immersed in their writings. While appreciating Paderewski as a man of political action rather than a creative artist and musician in the 1928 poem, Finley expressed his personal philosophy of liberalism and political involvement. Similarly to Paderewski, Finley took a path away from academic contemplation of the past towards an active involvement in the present, including both charity and politics. Another, celebrated instance of such a shift from the realm of “contemplation” towards “action”—though limited to charitable pursuits—was provided by Dr. Albert Schweitzer, who abandoned his research of J.S. Bach and a career as a organist and music historian for the sake of medical studies and working in a leper colony in Africa. Since the choices made by Finley and Paderewski both involved political motivation, it was harder to view both men as “modern saints.” Therefore, their impact on their societies has been underappreciated.

At present, the figure of John Huston Finley is of great interest to the historians of American literature and education. The revival of his heritage may be seen in calls to return to the “great books” tradition of liberal education that he championed for American students. In contrast, Paderewski’s generous vision of a large, powerful and multi-ethnic Poland was destroyed by the Nazis and Soviets. His reputation as a creative artist has also suffered numerous set-backs and rarely, if ever, is he venerated as an incomparable musical genius and a “modern immortal.”

Based on a popular image of Paderewski lecturing to Americans in 1915.

V. Johnson’s Tribute to a Patriot

When Robert Underwood Johnson (1853-1937) wrote his tribute to Paderewski in 1916, the composer’s transformation into a statesman, living a “vita activa”, had already begun.[33] Since 1915 Paderewski was involved in an extensive publicity campaign on behalf of Poland: during the years of World War I he gave over 350 speeches about the country’s need to become an independent state and preceded every concert with a half-hour talk on this subject. By continually and persistently shaping public opinion, while simultaneously engaging in seeking support in the highest political circles, Paderewski sought to achieve just one, main goal: the liberty for his country. His efforts were rewarded when President Woodrow Wilson added Poland’s sovereignty to his conditions for peace after World War I; sadly, even this achievement is discounted in the Paderewski entry in the New Grove II. Some documents pertaining to this area are discussed in “Paderewski and the Tenth Anniversary of Poland’s Independence” in the current issue of the Journal; additional remarks may be found in the editorial introduction and notes to this article.

The connection between Robert Underwood Johnson and Paderewski was probably established through Richard Watson Gilder: Johnson worked for the Scribner’s Monthly (later transformed into the Century Monthly Magazine) where he served as associate editor and Gilder was the editor-in-chief. After Gilder’s death, Johnson took over his post until retiring in 1913. A poet, editor, and diplomat, with family roots reaching far back into colonial times, Johnson was a literary celebrity, often called the unofficial poet laureate of the United States.[34] He published several volumes of poetry, often commemorating eminent individuals and events; he also co-edited the four-volume series of Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Among his other pursuits were: the international copyright movement, the creation of literary organizations, such as the Academy of Arts and Letters, and the preservation of American land and natural resources in national parks (with John Muir, the founder of the Sierra Club). Despite his appreciation of Paderewski’s patriotism, Johnson’s favorite European country was Italy; he worked for the Italian War Relief Fund of America, and after the war served as the American ambassador to Italy.

Johnson’s poem, To Paderewski, Patriot was hand-written on one page and its photographic reproduction is included in Orłowski’s collection of documents published in 1940.[35] Other publications of this poem are presently not known; its full text is included in Appendix I of this study. The four strophes of the poem consist of six verses each, with the parallel rhyme structure of aabbcc recurring in each strophe. The poem’s awkwardly angular symmetry results also from the identity of rhythmic patterns in each line and the placement of the accents on the last, single syllable. The poet described the composer as:

Son of a martyred race that long

Has honed its sorrow into song

And taught the world that grief is less

when voiced by Music’s loveliness.

In Johnson’s poem, Paderewski was the “bearer of memories” of his torn and suffering country that survived by cherishing remembrances of past glory through its “lost century of pride.” The poem included references to national travails and defeats; it concluded with an expression of hope that Paderewski’s “God-sent” musical gifts would serve and advance the Polish cause:

Master with whom the world doth sway

Like meadow with the wind at play

May Heaven send thee, at this hour,

Such access of supernal power

that every note beneath thy hand

May plead for thy distracted land.

The date of 13 April 1916 locates the poem’s likely origin in Washington, D. C. On that day Paderewski gave a recital at the National Theatre in the American capital.[36] The simplistic formal features of Johnson’s ode to Paderewski’s patriotism do not make his product appear very attractive at the threshold of the modernist era (it was written in the same year as James Joyce’s first major book, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man).[37] However, we should note that Johnson’s poetry had at least one prominent musical admirer, i.e. the American father of musical modernism, Charles Ives (1874-1954). In the 1920s Ives wrote songs to four poems by Johnson, including a longer excerpt of The Housatonic at Stockbridge, as well as At Sea, Luck and Work, and Premonitions. In Johnson, Ives found a fellow Transcendentalist; the composer also shared the poet’s interests in nature and its healing power. Paderewski’s interests had a different common trait with Johnson’s—i.e. classical-romantic aesthetic, characterized by an emphasis on the profundity of emotion and the comprehensibility of musical (or poetic) form. Johnson’s fascination with the romantic “giants” of English-language poetry active in the first half of the 19th century, such as Shelley, Tennyson, and Keats, was reflected in Paderewski’s belief that the greatest composers belonged to the early romantic period and included Beethoven, Schumann, Schubert, and Chopin.[38]

VI. Phillips, Paderewski and Poland

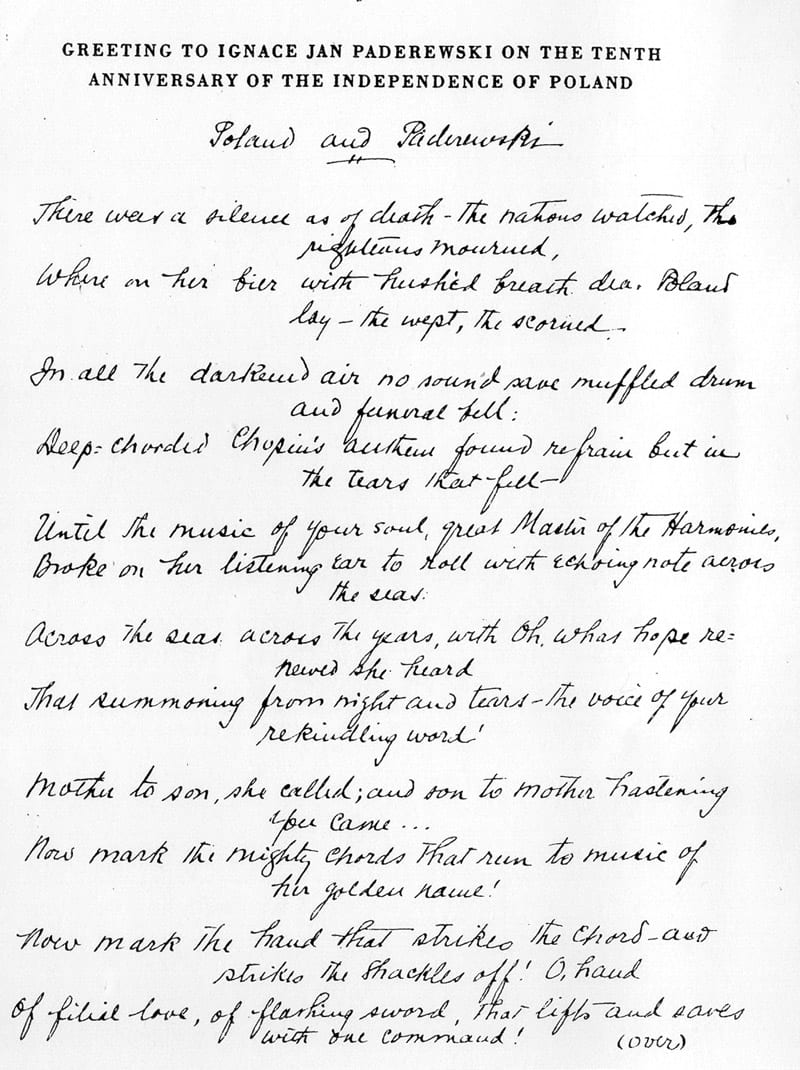

The final English-language poem to be considered in this overview was written by Charles Phillips (1880-1933), known to Paderewski scholars as the author of his popular biography,The Story of a Modern Immortal, published in 1933.[39] Phillips was a writer and poet, working as a professor of English at the University of Notre Dame (1924-1933), where his archives are now located. The Paderewski poem was penned for the celebration of Poland’s tenth anniversary of its independence and as a tribute to Paderewski’s role in this development during the celebratory dinner in New York in 1928. The same occasion was commemorated in verse by John H. Finley; as mentioned earlier the poems were included in an album of greetings (selected items are included in Part I of “Paderewski and the Tenth Anniversary of Poland’s Independence” in this issue of the Journal; the full text of the Phillips poem is enclosed in Appendix I to the current study; the first page is reproduced below or,  a larger image). In Paderewski and Poland, Phillips described the country’s resurrection as resulting from Paderewski’s actions:

a larger image). In Paderewski and Poland, Phillips described the country’s resurrection as resulting from Paderewski’s actions:

There was a silence as of death—the nations watched, the righteous mourned,

Where on her bier with hushed breath dear Poland lay—the wept, the scorned.

In all the darkened air no sound save muffled drum and funeral bell:

Deep-chorded Chopin’s anthem found refrain but in the tears that fell—

Until the music of your soul, great Master of the Harmonies,

Broke on her listening ear to roll with echoing note across the seas.

[…] Now mark the mighty chords that run to music of her golden name!

Now mark the hand that strikes the chord—and strikes the shackles off! O, hand

Of filial love, of flashing sword, that lifts and waves with one command!

[…]… She rises, beautiful, renewed! She lifts her golden voice—she sings—

And in her song, sweet plenitude of love, O, son, your bright name rings!

Since Paderewski’s first title to fame was his performing talents as a musician, Phillips abundantly draws from musical imagery in his text. It is Paderewski’s “kindling voice” that stirs Poland, his “mother,” back to life; it is the sound of music transcending any other human music that echoes in the breaking of the chains of the imprisoned country. As an international aid worker for one of the war victims’ relief agencies in Poland, Phillips had an opportunity to see the destruction and rebirth of Poland after World War I. He spent two years (1919-1920) directing the Polish relief efforts and wrote a book about the country. As a result of his charitable activities he was rewarded with the Polonia Restituta medal. During the period spent in Poland, Phillips had a chance to witness first-hand Poland’s reaction to Paderewski’s arrival and the outpouring of gratitude addressed to the musician-statesman. The first year of Phillips’s work there coincided with the composer’s brief sojourn as the president of the Polish council of ministers.

Paderewski’s first months in power were filled with public expressions of support and gratitude; crowds welcomed him during all his public appearances and he was portrayed in the press as Poland’s savior (for instance, two Polish poems discussed earlier by Święcicki and Wolska, both written in 1899, were published at that time). A detailed review of archival material is likely to increase this number of occasional verse praising Paderewski’s achievements. By the time Phillips wrote his poem though (1928), Paderewski’s active role in the Polish government had ended, and his erstwhile supporters were disappointed with his lack of success in negotiations of Poland’s borders and contentious issues with the country’s neighbors, Czecho-Slovakia and Germany. Moreover, in 1926, Paderewski’s main political rival, Józef Piłsudski, orchestrated a coup-d’etat that overturned the legally-elected government for the sake of a Piłsudski-controlled regime that was supposed to “heal” the disarray in the country (hence its name “Sanacja”).[40] These political circumstances further diminished the recognition of Paderewski’s political achievements in his home country and abroad. In these circumstances, the excessive praise found in Phillips’s poem and other tributes of the 1928 event, seem partly designed to rectify the historical record and recover Paderewski’s true significance, while countering the relentless propaganda of Piłsudski supporters. Needless to say, the portrayal of Piłsudski in Phillips’s biography of the composer (1933) was far from appealing.

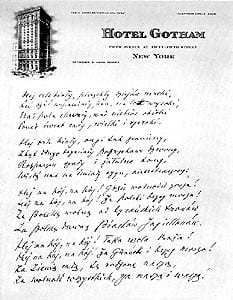

In the laudatory poem, Phillips’s statement about Paderewski’s voice calling out across the ocean to Poland may seem pure poetic licence. However, it is far more accurate than it would appear: Paderewski’s last composition was an anthem for the Polish Army in the U.S. that he was organizing in 1917-1918 in order to increase Poland’s presence in the battles of the Great War and to give credence to the country’s claim to a seat at the Peace Conference that was to define the new European order after the war. The composer penned the text for his anthem on a letterhead page from the Gotham Hotel in New York, his venue of choice during his American tours.[41] The manuscript of the poem’s text is not dated; the music was composed in 1917 and the song immediately sent out to be performed in the recruitment camps in the U.S. and Canada. According to the catalog of Paderewski’s manuscripts by Perkowska and Pigła, there are two sources for this song, entitled in both Orzeł Biały [White Eagle]: a 1918 edition, New York: T. Wroński (arrangement for male choir and piano or brass band); and an undated arrangement for mixed choir and brass band, copied by Henryk Opieński.[42]

The four-strophe song, with the incipit “Hej, orle biały” [Hey, white eagle!] which is usually used as a title, is addressed to Poland’s emblem, a proud bird of prey, that is encouraged to soar and lead Poles to valiant action. In the reprint in Appendix II, the Polish text—transcribed from Paderewski’s handwriting—is followed by an anonymous translation published in the volume by Orłowski (1940), with literal translations inserted in square brackets. The tone of the whole may be inferred from the following fragments:

[…]

Hej, orle biały, ongi tak zraniony,

Zbyt długo brzmiały pogrzebowe dzwony,

Rozpaczy szały i żałosne tony.

Wiedź nas na śmiały czyn, nieustraszony.

Translation:

On, white eagle, once so severely wounded!

Too long have rung the mourning chimes [lit. “resounded funereal bells”],

Lasted [lit. this word is not here] the mad despair and crying tunes [lit. “despair’s frenzy and mourning tunes”].

Lead us to brave and fearless deeds.

The final two strophes are addressed directly to the Polish troops and present them with their goals. The soldiers are to fight for freedom, for Polish access to the sea, for the recovery of the past glory of Poland’s two most powerful royal dynasties, the Piasts and the Jagiellons, and for universal liberty:

Hej na bój, na bój, gdzie wolności zorza,

Hej na bój, na bój, za polski brzeg morza.

Za Polskę wolną od tyrańskich tronów,

Za Polskę dumną – Piastów, Jagiellonów.

Hej, na bój, na bój! Taka wola Boża!

Hej, na bój, na bój! Za Gdańsk i brzeg morza!

Za Ziemie całą, tę ojczyznę naszą,

Za wolność wszystkich, za waszą i naszą.

Translation: On to fight! to fight! Where liberty is dawning!

On to fight for the Polish shore of sea!

For Poland free from tyrants’ fetters [lit. “thrones”]!

[additional line, missed in translation: “For Poland—proud—of Piasts and Jagiellons.”]

On to fight! Such is God’s will!

On to fight! For Gdańsk and seashore!

For all our land, our native land,

For the liberty of all, for yours and ours!

The last line is a reference to the motto embroidered on national flags since the 1848 Spring of the Nations, when the Polish troops led by General Józef Bem fought in the Hungarian uprising against the Hapsburgs. Paderewski’s poetic effort follows the conventions of a military song, expected to be simple, easily comprehensible and encouraging. Nonetheless, the text leaves much to be desired in terms of its literary quality. The rhymes are too obvious, the elevated language borders on the grotesque (e.g. “rozpaczy szały,” i.e. the frenzy of despair). However, Paderewski’s vision of a powerful Poland modeled on the multi-ethnic kingdoms of Poland’s Golden Age, hinted upon in several lines of his anthem, is notable for its far-reaching quality and political savvy. Paderewski, raised in the eastern part of Poland, where the towns were predominantly Jewish, villages—Ukrainian, and manors—Polish, was opposed to the notion that Poland could ever become an ethnically-united “nation-state.” He knew that large ethnic minorities were interspersed throughout Poland’s territory and that the country could not have been defined in narrow ethnic terms without serious internal and external problems.[43] In addition, Paderewski’s territorial emphasis on creating Poland with full access to the Baltic Sea and the inclusion of the port-city of Gdańsk was prescient in the light of the awkward, and ultimately dangerous, construct that emerged as a result of the Versaille Peace Treaty: a free city of Danzig, and a corridor of Polish land separating two German enclaves. It was the Polish resolve not to give in to Hitler’s demands for a corridor of land that would have connected both German-held parts of the seashore that provided him with a direct excuse to attack Poland and start World War II in 1939.

Despite the political wisdom apparent in his vision of a large, multi-ethnic and powerful Poland, Paderewski’s patriotic song has not been widely recognized or very popular. It rarely appeared in printed collections of military songs in Poland or abroad. Of the sources I consulted, Paderewski’s hymn of the Polish Army was not included in any currently used anthologies or CD collections. Yet, it marks a decision that changed the course of Paderewski’s career and ultimately influenced his standing as a composer and statesman: as a Polish national hero he disappeared from the annals of music history, as a piano virtuoso and an “idol” of the crowds, he was not a typical politician either. Paderewski’s Hej, orle biały, thus occupies a peculiar place among the “last works” by composers, that have included a series of ninth or tenth symphonies (Beethoven, Bruckner, Mahler), and the unfinished Kunst der Fuge (Bach).

VII. Paderewski Elegies

By 1941, Paderewski’s own music was nearly forgotten. The war-themed symphonies performed during World War II included Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony and not Paderewski’s Symphony in B minor, Polonia (though Aleksander Tansman’s equally patriotic, notably shorter Polish Rhapsody was receiving performances throughout the U.S.). [44] The aging artist was still highly recognized as the living symbol of Poland’s independence and invited to chair the National Council, the kernel of the Polish government-in-exile. No wonder then, that Paderewski’s death in 1941 resulted in occasional poetry of a patriotic nature. According to Marian Marek Drozdowski, who studied Paderewski’s political career, a poem by Włodzimierz Bakalarski was often recited in military camps, in Switzerland, Scotland, Wales, and the Near East, through 1942-43.[45]

Niech wszystkie wierzby w kraju się rozpłaczą

I te przydrożne i te nad strumieniem…

Gdy Cię oczami w zaświatach zobaczą,

jak szopenowskim będziesz kroczył cieniem.

Lekko trąć liśćmi, a na wiatru strunach

wypieść akordy, co łkają Ci w duszy.

Niech Wiosna Ludów przebudzi się w łunach

i całą łunę w fundamentach ruszy.

Niech się Mazowsze rozśpiewa, rozdzwoni,

w takt kujawiaka, mazurkiem ułańskim…

[…]A wtedy zbrojnie ruszą wszystkie stany

i duch Twój będzie znów przewodził ludem…

Gdy zagrasz światu—Mistrzu Ukochany –

Rewolucyjną Szopena etiudę!!!

Translation:

Let all the willows in the country weep

those by the roads and those by the streams…

when they see you—with their eyes—in the otherworld

as you walk in Chopin’s shadow.

[…]

When—with the sounds of the sonata, in the moonlight silence –

Poland will be filled with the tender sorrow,

cast the threads of alarm into heaven!

And then all the states [i.e. classes of society] will rise to arms

and your spirit will again lead your people…

when you will play for the world—you, our Beloved Master—

[will play] Chopin’s Revolutionary Etude.

Bakalarski describes Paderewski’s most popular pieces as reflections of Poland’s landscape and its regions: the dances resound in the central area of Mazovia, the Tatra Album resounds with echoes in the mountains from which the music originated, and the waves of the Baltic Sea sway in the gentle rhythm of the ever-popular Minuet (in G major). There is an allusion to the “moonlight silence” i.e. the Moonlight Sonata—the subtitle of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 27 no. 2 and the title of the only movie in which Paderewski acted (1936). [46] The grand finale, though, is reserved for Chopin’s music: it is the tones of Chopin’s Revolutionary Etude that would result in the patriotic resurgence, not Paderewski’s own Hymn of the Polish Army, or his Symphony Polonia. For Paderewski, it seems, Chopin’s shadow was too large to be cast off. Despite his repeated efforts at creating a national opera (Manru), symphony (Polonia), or piano repertoire (various collections of dances and program pieces), Paderewski’s presence in the popular imagination, even among his compatriots was primarily as a performer. It is also worth noting that his political achievements in securing Poland’s independence a quarter century earlier are not even mentioned in Bakalarski’s final tribute to Paderewski, the charismatic patriot and inspired musician.

Personal sentiments about the nature of death and dying witnessed by a child are found in a personal elegy published by the daughter of Paderewski’s secretary, Sylvan Strakacz, Anne Strakacz-Appleton. The Polish text of this poem is found in Strakacz-Appleton’s “Wspomnienie o Paderewskim” in the anthology of Paderewski studies edited by Wojciech Marchwica and Andrzej Sitarz (1991). [47] Strakacz-Appleton writes:

Pożegnał nas uśmiech zza progów człowieka.

W nim wszystko spoczęło: i droga daleka,

i koniec tak bliski, i krzyż bohatera

o który się ludzkość bezsilna opiera;

i gwiazda za którą król idzie wybrany

by drogę wskazywał tym nędzniej odzianym.

Translation:

Our last farewell was the man’s smile from beyond the threshold.

Everything rested in it: the long way,

the imminent ending, and the cross of the hero

that provides the support for powerless humankind;

the star that is followed by the king chosen

in order to show the way to those dressed more poorly.

While still belonging to the genre of “elegiac poems” about Paderewski and touching upon the mystical themes of religious nationalism (with veiled references to Christianity and a quotation of a title of Juliusz Słowacki’s play, Król Duch [The King Spirit]), Strakacz-Appleton’s expression of personal grief initiates a new category of poetry dedicated to the pianist-composer. It could be called “personal-sentimental response” for lack of a better label. Simultaneously, its heart-felt sentiments indicate a return to the earnest devotion of Paderewski’s early listeners, like Polish exiles in Belgium who, in awkwardly-rhymed lines, “gave him their hearts.” For his Polish compatriots, Paderewski was the country’s favorite son and its “savior;” this role of the “new Chopin” was far more important than his engagement in purely musical pursuits—i.e. his image as “Master of Harmonies” praised by Gilder, Finley, and Phillips. In poetic reception of Paderewski in Polish culture, politics triumphed over art.

Notes

[1]. The term “modern immortals” was often used in reference to famous people, e.g. Ghandi, Einstein, and Paderewski. In the 1920s and 1930s it did not seem to have the same connotation as at present. Paderewski was listed in studies of such “immortals” and referred to by this term in: Charles Phillips, Paderewski. The Story of a Modern Immortal. (New York: Macmillan, 1933); and William Kimberly Palmer, Immortal Jan Ignace Paderewski (a poem, Chicopee, Mass., 1934). [Back]

[2]. This subject has been examined in several dissertations written at American universities: David J. Morck, Ignace Paderewski and the Re-Birth of the Polish State, 1914-1919, (M.A. thesis, California State University, Fullerton, 1994); Joseph T. Hapak, Recruiting a Polish Army in the United States, 1917-1919, (Ph.D. diss., University of Kansas, 1985); Mieczyslaw B. Bienkowski-Biskupski, The United States and the Rebirth of Poland, 1914-1918, (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1981). Authors of Paderewski’s political biographies wrote about it in Poland: Marian Marek Drozdowski, Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Zarys biografii politycznej [Outline of a political biography] (Warsaw, 1979; Eng. trans., 1981, enlarged 1988); Henryk Przybylski, Paderewski: Między muzyką a polityką [Paderewski: Between music and politics] (Katowice: Unia, 1992). [Back]

[3]. There is only one copy of this poem, held in the library of Brown University; it was issued as a pamphlet, or broadside in Chicopee, Massachusetts. Paderewski did not give concerts in the U.S. in 1934, as his wife died that year and he did not travel far; in 1933 he performed in New Haven, Conn.; Boston, Mass; New York, Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Washington, D.C. See Małgorzata Perkowska, Diariusz koncertowy Paderewskiego [Paderewski’s concert diary] (Kraków: PWM, 1990), 189. [Back]

[4]. Details about Paderewski’s travels and performances are taken from two main sources: Andrzej Piber, Droga do sławy: Ignacy Paderewski w latach 1860-1902 [The path to fame: I. P. in the years 1860-1902] (Warsaw: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1982) and Perkowska, op. cit. [Back]

[5]. Piber, op. cit., p. 166. Piber’s note probably includes a wrong date of publication of this poem in Dziennik Poznański; according to Dr. Barbara Zakrzewska—for whose assistance in this matter I am very grateful— this poem cannot be found in the listed volume of the Dziennik, as found in the collection of the Library of the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. [Back]

[6]. See Perkowska, op. cit., p. 42; Piber, op. cit., p. 166, 543. [Back]

[7]. The poem is cited from Piber, p. 543; the original is found in Archiwum Paderewskiego in Warsaw Archiwum Akt Nowych, no. 587, p. 1. [Back]

[8]. See Piber, op. cit., p. 337. [Back]

[9]. Henryk Sienkiewicz (1846-1916) wrote a series of popular historical novels, including The Flood and Quo Vadis?; the latter received a Nobel Prize for literature. Leopold Julian Kronenberg (1849-1937), a banker, industrialist and composer, heir to the family fortune, invested in railroads and sponsored the building of the Warsaw Philharmonic. [Back]

[10]. The Album is located in the Paderewski Archives in Warsaw, Archiwum Akt Nowych, no. 69. [Back]

[11]. See Tadeusz Dobrowolski, Malarstwo Polskie (Wrocław: Ossolineum, 1989): 178-183. [Back]

[12]. Maryla, or Maria Wolska, née Młodnicki (1873-1930) studied painting in Munich and Paris, but later dedicated all her efforts to poetry. She held a literary salon in her mansion in Lwów; her poetry draws upon characteristic fin-de-siècle themes of pessimism and misgivings of death. [Back]

[13]. Piber cites only one strophe by Wolska from this joint poem; it is found in the notes on p. 583 of his 1982 study. [Back]

[14]. Perrault and Brothers Grimm, in The Mammoth Book of Fairy Tales, edited by Mike Ashley (London: robinson, 1997). “Little Snowdrop; or, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” by The Brothers Grimm p. 271-280; and “Sleeping Beauty” by Charles Perreault, p. 417-426. [Back]

[15]. The Polish tale about sleeping knights under the rocky peak of Giewont may be found in Na Skalnem Podhalu [On the Rocky Foothills] by Kazimierz Przerwa-Tetmajer (1865-1940), published at the end of the 19th century (Warsaw: Nakł. Gebethnera i Wolffa, 1902, 2nd ed.); numerous later reprints use a variant of the title caused by changed spelling: Na Skalnym Podhalu. [Back]

[16]. The postcard is signed by A. Piotrowski, the middle name (sometimes used) of Maksymilian Piotrowski was Antoni; see Dobrowolski, op. cit., 168. [Back]

[17]. Richard Watson Gilder (1844-1909); see The Cambridge History of English and American Literature: An Encyclopedia in Eighteen Volumes, ed. by A.W. Ward, A.R. Waller, W.P. Trent, J. Erskine, S.P. Sherman, and C. Van Doren (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons; Cambridge, England: University Press, 1907-21). Piber, op. cit., 214-215. [Back]

[18]. Zamoyski, op. cit., 101, 124. The biographer’s statements are based on Gilder’s Letters, Rosamond Gilder, ed. (New York: 1916), p. 216. [Back]

[19]. Information based on the entry by Herbert F. Smith, in Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 64: American Literary Critics and Scholars, 1850-1880, John W. Rathburn, Monica M. Grecu, eds. (The Gale Group, 1988. pp. 71-77). See also R. W. Gilder, The Poems of Richard Watson Gilder (Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1908); Five Books of Song (New York: The Century Co., 1894); The Fire Divine (New York: The Century Co., 1907). [Back]

[20]. Richard Watson Gilder, A Book of Music (New York, The Century Co., 1906). [Back]

[21]. The poem, published in A Book of Music was cited by Arthur V. Sewall during the ceremonial dinner for Paderewski in 1928; the full text of this speech, including an extended fragment of the poem is included in Part II of “Paderewski and the Tenth Anniversary of Poland’s Independence,” in this issue of the Journal. [Back]

[22]. Biographical data about Finley are based on an entry in Dictionary of American Biography, Supplements 1-2: To 1940. (American Council of Learned Societies, 1944-1958. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: The Gale Group, 2001; http://www.galenet.com/servlet/BioRC) [Back]

[23]. See Marvin Gettleman, An Elusive Presence: The Discovery of John H. Finley and His America (Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1979). [Back]

[24]. The publications are selected from items found in the OCLC online catalog, WorldCat. [Back]

[25]. Details about the tour are based on information from Perkowska, op. cit., 136, passim. [Back]

[26]. Extended excerpts from this poem are included in Finley’s speech at the celebration of Poland’s Tenth Anniversary in 1928; the speech is reprinted in its entirety in Part II of “Paderewski and the Tenth Anniversary of Poland’s Independence,” in the current issue of the Journal. [Back]

[27]. All the references to ancient Greece are explained in notes to Part II of “Paderewski and the Tenth Anniversary…” The characters, places and actions are those described by Homer in the epic poem, the Illiad. [Back]

[28]. Andrew Lang’s translation of Homer’s Illiad was first published in 1905 and repeatedly reprinted with illustrations in the 1930s. [Back]

[29]. Women’s response to Paderewski’s performances was so intense and overwhelming that it foretold the modern cults of Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley and the Beatles; its examination is an engaging topic for a feminist musicology project.[Back]

[30]. For an in-depth study of all aspects of Greek music, see Thomas J. Mathiesen, Apollo’s Lyre: Greek Music and Music Theory in Antiquity and the Middle Ages (University of Nebraska Press, 1999). [Back]

[31]. Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958). See also Daniel Mano, Relating Vita Activa and Vita Contemplativa Hannah Arendt on the Human Condition (Ph. D. diss., University of Waterloo, 1992); H. Arendt and Melvyn A. Hill, Hannah Arendt, the Recovery of the Public World (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1979). [Back]

[32]. The quotation below comes from Arendt, op. cit., pp. 176, 179, and 198.[Back]

[33]. Robert Underwood Johnson, American poet and diplomat. Biographical information may be found in World Authors, 1900-1950 Martin Seymour-Smith and Andrew C. Kimmens, eds. (Wilson, H.W., 1996); Alden Whitman, American Reformers: An H.W. Wilson Biographical Dictionary (Wilson, H.W., 1985). [Back]

[34]. The American office of “poet laureate” was established by the U.S. Congress only in 1985; the position is temporary and involves serving as a poetry advisor to the Library of Congress. In the British tradition, the “poet laureate” had the task of writing verses about the royal family; the first official poet laureate was John Dryden (1668). [Back]

[35]. Józef Orłowski, Ignacy Jan Paderewski i Odbudowa Polski [I.J. Paderewski and the Rebuilding of Poland] vol. 2 (Chicago: The Stanek Press, 1940), p. 124. [Back]

[36]. Data about the concerts from Perkowska, op. cit., 141. [Back]

[37]. James Joyce (1882-1941), A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (New York: Huebsch, 1916; London: Egoist, 1917); Ulysses (Paris: Shakespeare & Company, 1922; London: Egoist, 1922; New York: Random House, 1934). [Back]

[38]. For references to Paderewski’s efforts to promote these composers, see Piber, op. cit., 293, 375; Zamoyski, op. cit., 134. [Back]

[39]. Charles Phillips, Paderewski, the Story of a Modern Immortal (New York: MacMillan, 1933; reprinted in New York: Da Capo Press, 1978; reprint lists the publication date as 1934). This biography is listed in every subsequent book on Paderewski. [Back]

[40]. See Norman Davies, God’s Playground: A History of Poland (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), vol. 2. For discussions of Paderewski and Piłsudski see Marian Marek Drozdowski, Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Zarys biografii politycznej [Outline of a political biography] (Warsaw, 1979; Eng. trans., 1981, enlarged 1988). [Back]

[41]. Paderewski’s undated manuscript of the song’s text and the first page of the 1918 printing by T. Wroński are reproduced on pp. 12-13 of Orłowski, op. cit.[Back]

[42]. Małgorzata Perkowska and Włodzimerz Pigła, “Katalog rękopisów I.J. Paderewskiego” [Catalogue of manuscripts by Paderewski], Muzyka 33 no. 3 (1988): 53-70.[Back]

[43]. While Paderewski’s name was used for various political causes, especially by the nationalist faction of Roman Dmowski, he did not share Dmowski’s anti-semitism and was supportive of the role of minorities in the independent country. See Zamoyski, op. cit., 143-144. [Back]

[44]. Aleksander Tansman’s Rapsodie polonaise (1940) connected the melodies of the Polish and British national anthems, as an expression of hope that Britain would come to the rescue of its beleaguered ally. The work was performed in the U.S. through the war years. [Back]

[45]. See Marian Marek Drozdowski, “Reakcje świata na śmierć Paderewskiego,” in Wojciech Marchwica and Andrzej Sitarz, eds., Warsztat kompozytorski, wykonawstwo i koncepcje polityczne Ignacego Jana Paderewskiego [Composers workshop: Performance and political conceptions of Ignacy Jan Paderewski] (Kraków: Musica Iagiellonica, 1991), 20-34. The poem is cited on pp. 24-25. [Back]

[46]. The black-and-white Moonlight Sonata was released in 1937 in England; it includes a twenty-minute Paderewski recital with Chopin’s Polonaise Op. 53, Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody, Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata and Paderewski’sMinuet in G-major.. [Back]

[47]. Anne Strakaczówna-Appleton, “Wspomnienie o Paderewskim,” [Remembering Paderewski], in Marchwica, Sitarz, eds., op. cit., 5-19. [Back]

Appendix I: Poems About Paderewski

Compiled and translated by Maja Trochimczyk

Anonymous [“Halka”]: The Portrait of Paderewski (1917)

NOTE: This poem was reprinted in The Musical Courier on 22 February 1917; the press clipping was found in the Research Collection, Performing Arts Division, New York Public Library. The original publication was the Von Ende Bulletin issued by the Von Ende School of Music, where Zygmunt Stojowski was a faculty member.

Hair of flaming sun!

Eyes of the mystic sea!

Archangel of our muse!

IGNACE Paderewski.

King of glorious Poland!

God made him fit to be

A nation’s wish (fate willing)

IGNACE JAN PADEREWSKI.

Waldemar Bakalarski: Paderewski (1941)

NOTE: Biographical information about Bakalarski is currently unavailable. The poem was published in numerous ephemeral bulletins, and newsletters, and widely disseminated during the World War II, but has not been available since. The current version is reprinted from Marian Marek Drozdowski, “Reakcje świata na śmierć Paderewskiego,” in Wojciech Marchwica and Andrzej Sitarz, eds., Warsztat kompozytorski, wykonawstwo i koncepcje polityczne Ignacego Jana Paderewskiego [Composers workshop: Performance and political conceptions of Ignacy Jan Paderewski] (Kraków: Musica Iagiellonica, 1991), 24-25.

Niech wszystkie wierzby w kraju się rozpłaczą

I te przydrożne i te nad strumieniem…

Gdy Cię oczami w zaświatach zobaczą,

jak szopenowskim będziesz kroczył cieniem.

Lekko trąć liśćmi, a na wiatru strunach

wypieść akordy, co łkają Ci w duszy.

Niech Wiosna Ludów przebudzi się w łunach

i całą łunę w fundamentach ruszy.

Niech się Mazowsze rozśpiewa, rozdzwoni,

w takt kujawiaka, mazurkiem ułańskim…

a echo górom niech się w pas pokłoni,

niezapomnianym Albumem Tatrzańskim!

Potem odbite od skalnych pancerzy

inną pobiegnie sprawować widetę;

nad Bałtyk szary, do morskich wybrzeży

i rozkołysze fale Menuetem.

Dźwiękiem sonaty, w księżycowej ciszy

Gdy się rzewnością Polska już nasyci—

i cisnij w niebo alarmowe nici!

A wtedy zbrojnie ruszą wszystkie stany

i duch Twój będzie znów przewodził ludem…

Gdy zagrasz światu—Mistrzu Ukochany –

Rewolucyjną Szopena etiudę!!!

Translation:

Let all the willows in the country weep

those by the roads and those by the streams…

when they see you—with their eyes—in the otherworld

as you walk in Chopin’s shadow.

Touch lightly with leaves, caress—on the wind’s strings –

the chords that sob within your soul.

Let the Spring of the Nations awake in firelight

and let it stir the whole light to its foundations.

Let Mazowsze sing, let it resound

with the beat of the kujawiak, with the ulan mazurka…

and let the echo bow down to the mountains

with the unforgettable Tatra Album.

Then, reflected from the armor of the rocks

let the echo run to a different vignette –

towards the grey Baltic, to the shores of the sea –

and let it move the waves with the Minuet.

When—with the sounds of the sonata, in the moonlight silence –

Poland will be filled with the tender sorrow,

cast the threads of alarm into heaven!

And then all the states [i.e. classes of society] will rise to arms

and your spirit will again lead your people…

when you will play for the world—you, our Beloved Master—

[will play] Chopin’s Revolutionary Etude.

Henryetta Teresa Beckert: [Tribute to Paderewski] (n.d. ca. 1916)

Note: This short tribute was inserted into a portrait of Beckert with a picture of Paderewski in hand, cited from Orlowski, op. cit, p. 90. Beckert came from a Silesian noble family, with musical talents and an intense interest in Paderewski. Orlowski writes: “She is convinced that His Genius will resurrect a free Poland for the second time and that this country will be beloved by all—also like Paderewski.”

Jestes Geniuszem, zrodzon z milosci

Twego Narodu, Twojego ludu—

Twoj zywot wieczny—Tys niesmiertelny

W pracy wysilku, wiedziesz do cudu—

Musim zwyciezyc za Twym przewodem

Bosmy Polacy i Twoim Narodem.Translation:You are a Genius, born of love

Of your Nation, love of your People—

Your life is eternal—you are immortal

In strains of labor, you lead us to a miracle—

Under your guidance we have to win

Because we are Poles, we are your Nation.

Andrzej Czyżowski: Na śmierć Paderewskiego [For the death of Paderewski] (1984)

NOTE: This patriotic poem was published in Polish, in a Polish-American newspaper Gwiazda Polarna, on 7 July 1984. Press clipping from the Paderewski files in the Polish Music Center at USC.

Gdy od otwartej trumny, jak od świętego ołtarza,

Odeszli swoi i obcy, artyści, muzycy, malarze—

Zmienili świece kościelni, zamietli kościół dozorcy,

Bramę za sobą zamknęli. Jak uroczysty egzorcyzm

Huk zatrzaśniętych drzwi zajęczał w rurach organów

Cało zostaje samo—do jutra rana.

Od wieńców kwietnych zapach po sali wionie,

Ktoś jeszcze siedzi przy trumnie, twarz ukrył w dłoniach

I trwa tak w ciężkim bezruchu, jakby coś długo wspominał.

Zaskrzypiał zegar na wieży. Wybiła jakaś godzina…

Powoli wstał ze stopni, starcze prostując kolana,

Pochylił sie nad zmarłym, nad twarzą ze srebra odlaną

I żegnał tę siwą głowę, swoją, lecz już nie własną:

Żegnam was, ręce zmęczone jak moje serce.

Nie będę wami płakał w Szopena scherzu,

Żegnam was, oczy i usta, i uszy spowite w ciszę.

Nie będę mówił ni patrzył, nie będę słyszaę

I dla tej mojej ziemi nic tu już zrobić nie zdołam,

Choć wiem i czuję, jak cierpi—jak moja ziemia woła…

Myślałem sobie: Gdy umrę, powiozą mnie z powrotem.

Tą jedną żyłem chęcią, tą jedną gasłem ochotą,

Żeby—gdzie żyć nie mogłem—po śmierci spoczywać spokojnie.

Spaliła się moja starość w pożarze wojny…

Odwrócił się i zszedł tam, gdzie na aksamicie

Leżały wszystkie ordery zebrane przez całe życie.

A były tam gwiazdy i runa, i wstęgi, złote korony—

Schylił się nad ostatnim. Na chuście białoczerwonej

Jaśniał żołnierski krzyż—za śmierć mu go dali.

Miał prosty wyraźny napis: Virtuti Militari.

Ujął w swe ręce przejrzyste krzyż owinięty w proporzec

I tak wyruszył w drogę.

Ciemno było na dworze,

A on szedł ciągle pod górę, wytrwale i bez zmęczenia.

Po drodze tak sobie układał, jak to z Panem Stworzenia

On będzie teraz rozmawiał.

Tak ciągłe idąc do nieba i myśląc, Pan Ignacy

Doszedł do końca ścieżki—do końca ścieżki przeznaczeń.

A na początku Mlecznej Drogi, pod mlecznym drzewem,

Przywitali go żołnierze żołnierskim śpiewem.

Wysoka trąbka zapiała srebrnym sygnałem,

Ozwało się trąbek tysiące na błoniu całym.

Do koni się porwały ułany na alarm,

Pod nogami biegnących cała ziemia zadrżała.

Brzmią rozkazy. Pośród kurzu i grzmotów

Zadudniła buciskami piechota.

Stojuą wojska przy drodze na błoniach,

A na czele Skotnicki na koniu.

Czarny łeb, krwią zlepiony, dumnie do góry trzyma,

A wkoło generały: Wład, Kustroń i Olszyna,

Na sobie pysznie noszą szkarłatno-krwawe szarfy

Dientorf-Ankowicz, Bołtuć, Podhorski i siwy Alter.

Skurzone piękne mundury, schlastane długie buty—

Ej, poznać po generałach ostatnią, śmiertelną marszrutę.

Kiwają się na koniach w strzaskanych stalowych hełmach