by Maria Anna Harley (Maja Trochimczyk)

Originally published on the PMC website on 18 December 1997

Poland, a tiny country in comparison with the United States, is five times older as a nation. This difference in age is nowhere more obvious than in the music. The history of Polish music begins with the acceptance of Christianity by the Slavic nation in the 10th century. American music arises from the rich heritage of many immigrant communities and the cultural mosaic of native traditions that have made the United States a microcosm of the world.

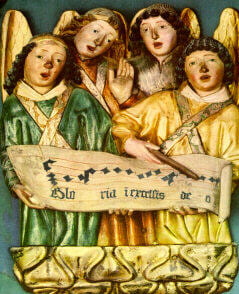

Polish music history commences with the liturgical chants of the Latin Church that reached Poland from Rome via neighboring Bohemia. The arrival of a new cultural practice fostered an outpouring of religious music, much of it centered on the praise and worship of the Virgin Mary. Bogurodzica [The Mother of God] is the earliest hymn notated in Polish; its earliest preserved sources date from the 15th c. while the chant itself is said to have been composed in the 13th century. The text is a document in the history of the Polish language as well as the country’s earliest “national anthem:” Bogurodzica was sung by the Polish army in defensive wars with the Knights of the Cross, most notably at Grunwald (1410).

Other famous hymns were written to praise Polish saints, such as St. Adalbertus and St. Stanislaus, the addressee of Gaude Mater Polonia [Rejoice, Mother Poland], which is still sung at official university events, e.g. the beginning of the academic year. The notated music of the Church was preceded, however, by an oral musical tradition of the pre-Christian Slavs, which many believe to have survived in the treasury of Polish folklore that has inspired numerous composers, with the best known names of Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) and, recently, Henryk Mikolaj Gorecki (b. 1933). The folklore of Poland differs from one area to the next: the music of Mazovia (in central Poland) is often taken as the “standard” Polish form of folk music with its array of dance forms, such as mazurkas, obereks, polkas, etc.). The distinct styles of songs and instrumental music preserved in the Tatra Mountains (Gorale music [listen!]), and in the lake district in the North-Western Poland (Kurpie region) are of particular interest, especially because of their current cultural vitality.

Yet, it is the heritage of religious music, preserved in richly ornamented manuscripts, that reveals the great talents of Polish composers such as Waclaw z Szamotul (born c1524, died c. 1560), Mikolaj Zielenski (17th c., dates unknown; his works were published in Venice), Marcin Mielczewski (died in 1651) and many others. These eminent artists did not work in isolation, but benefited from lively cultural contacts between Poland and other European countries. The 16th and 17th centuries, periods of economic prosperity and peace, created ideal conditions for the cultivation and advancement of all the arts — it was the Golden Age of Polish culture. Various forms of secular and religious music thrived; musicians from Hungary, Italy, France, and Germany found employment at the royal court (Wawel Castle in Krakow, Cracovia–as pictured in the print; the site when the famed tapestries are held), in the chapels of the aristocracy, and in the church. It was during this period that Polish art music took form and flourished, with its forms of vocal polyphony (choral music), dances for the court, and various types of songs for one and many voices.

In 1569, the treaty of Lublin united Poland with Lithuania (the result of an earlier marriage between the royal families of the two countries). Since that time, Poland’s cultural and ethnic amalgam has included Germans, Jews, Ukrainians, Byelorussians, Scandinavians and Tartars, along with ethnic Poles and Lithuanians. The religious mix has comprised Roman Catholics, Jews, Orthodox, Protestants and Muslims. Each of these cultural groups has significantly enriched Poland’s musical life, but their role in the development of Poland’s musical heritage has not been fully examined.

The 18th century was for Poland a time of wars and internal instability, culminating in the 1790s with the partition of the country among Austria, Russia and Prussia. Poland no longer appeared on maps of the world. In these distressing circumstances, the musical life suffered and regressed. However, Polish composers continued to create works in styles popular in contemporaneous Europe, such as symphonies [listen to a Symphonie by Wanski] and operas.

Throughout the 19th century, Poland strove unsuccessfully to regain its independence. During this period, the greatest Polish composer, Fryderyk Chopin, became a national symbol of resistance and a source of cultural identity. His Polish audiences loved the Polonaises and Mazurkas, though some of his music was considered to be too difficult for the average music lover. Many myths surrounded the creative life and artistic persona of this wonderful composer, whose works belong to the international standard repertoire of all pianists [listen to Krystian Zimerman play the Grande Valse Brillante]. Chopin’s music and artistry provided models for successive generations of musicians, who, like the later Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937), sought to create and sustain a distinct national style derived from folk music and songs. Polish composers of the 19th century included those who created music for the home and homeland and those who chose a life of traveling virtuosi, and wrote music of great technical difficulty and brilliance. The best example from the first group is Stanislaw Moniuszko (1819-1872), the father of the national opera (Halka, The Haunted Manor), and the author of the large and ever-popular Home Songbooks collection.

His counterpart in the second group is Henryk Wieniawski (1835-1880), a renowned violin virtuoso who traveled around Europe and whose output includes Caprices and Concerti well known to many violinists today. Wieniawski’s predecessors, engaged simultaneously in composition and virtuoso performance, included Maria Szymanowska (1789-1831), a pianist-composer of Polish-Jewish roots and an international fame.

In 1918, after the First World War, Poland became, once again, an independent country. Until the invasion by Germany in 1939, Polish music prospered, due in large measure to close cultural contacts with other European countries as well as with North America. During this period a number of highly talented composers arose in the shadow of Szymanowski, undoubtedly the father of modern Polish music [listen to one of his Mazurkas]. Szymanowski encouraged his students and colleagues to study in Paris and to shed the stylistic dependence on German music that he himself was not free from in his early years. The neoclassical style and the lightness of the French “esprit ” inspired, before Szymanowski, Aleksander Tansman (1897-1986), who was, for a time, the best-known Polish composer. During years spent in Paris Tansman used to introduce himself: “Je suis un compositeur polonais” and he did not relate to his Jewish background until the rise of Hitler to power. After surviving the war in California and his subsequent return to Paris, Tansman was overshadowed by the younger avant-garde composers, such as Krzysztof Penderecki (b. 1933) or Gorecki (who enjoyed considerable government support for their work).

The most recent chapter in the history of Polish music was written in the socialist period between 1945 and 1989. The years 1949-1956 may be best described as the heights of Stalinist terror; at that time, the official ideology of the state constrained the arts by stylistic requirements of socialist realism. In music, “realistic” meant “folk-oriented, simple, neo-romantic,” with more advanced creative efforts banned as symptomatic of “formalism” and the genres of mass song, cantata to praise the government, children’s songs, practiced by most composers living in the country. Luckily for the fate of Polish music, this rigorous approach was soon replaced with a much more lax one: music was defined as abstract in its essence and, therefore, free from the necessity to be “realistic.” From 1956, when the first Warsaw Autumn International Festival of Contemporary Music took place, till the fall of the socialist government in 1989 composers, especially those who refrained from political activities, were free to do as they pleased (as long as the subject matter and titles of their works avoided political controversy). During the 1960s Western critics began speaking about a “Polish school of composition” created by Gorecki, Penderecki, Kazimierz Serocki, Witold Lutoslawski (1913-1994), Wojciech Kilar (b. 1932) and many others. The delicate and refined textures of Lutoslawski’s music found many admirers around the world [listen to Anne-Sophie Mutter play Chain II]; other, more aggressively dissonant works seem to have aged less gracefully.

Nonetheless, the cultural policies of the communist government left a legacy of strong support for non-figurative arts, a universal system of musical education, and the wide dissemination of information on composers, performers and their achievements. This favorable heritage was marred, however, by a record of political repression and the cultivation and promotion of a monolithic concept of ethnic Polishness. Knowledge about rich and varied heritages of cultures thriving in the Kingdom of Poland was not disseminated; the issues of ethnic backgrounds and regional loyalties of composers were ignored. One of the advantages of the governmental support for the art of music was the emphasis on gender equity and its result in the form of growing numbers of talented women composers, beginning from Grazyna Bacewicz (1909-1969). A disciple of Nadia Boulanger, a prize-winning violinist and composer, Bacewicz became one of the main figures in the Polish musical establishment after World War II. Her instrumental music, characterized by vitality, humor and a “joy of life” remains a favorite with musicians and music lovers. One of her younger colleagues, technical difficulty and brilliance. The best example from the first group is Marta Ptaszynska (composer and percussionist) enjoys an increasing international recognition as a leading compositional talent.

Today, music is thriving in Poland, and composers have the status of celebrities. If you ask a Polish man or woman on the street who is “Gorecki” or “Chopin” everyone would know. If you were to ask them to name one living composer the name of “Penderecki” would be mentioned. But if you were to repeat the same test in the U.S, it is highly unlikely that anyone who is not a musician would mention Steve Reich, or Elliot Carter.

Poland cherishes its musical heritage, enriched and sustained over the past thousand years. There are innumerable festivals, concert series and competitions through the year; musical events take place in large cities and small towns or villages. Even the smallest communities strive to celebrate their uniqueness with music. If you happen to be traveling on a LOT Polish airliner to Warsaw, tune in to the “Chopin” music channel on board. Listen to his Polonaises and Mazurkas, and you’ll experience the spirit of Poland before your feet touch Polish soil.