Essay by Maja Trochimczyk

History

The polonaise is a stately Polish processional dance, performed by couples who walk around the dance hall; the music is in triple meter and moderate tempo. The dance developed from the Polish dance (taniec polski) of the 18th century; this form, in turn, was derived from the chodzony (walking dance) which was popular in the 17th century and known as a pieszy (pedestrian), or chmielowy (hops) dance. The latter form had its roots in the folk wedding dances, from which it separated and then entered the dance repertoire of the nobility. The folk variants continued to develop independently of the “Polish dance,” resulting in such dances as chodzony, chmielowy (in the villages), and świeczkowy (in the towns). The Polish name of the dance, polonez, stems from the polonized form of the French term polonaise which was introduced in the 17th century (also accepted in English); the Polish term replaced the earlier name of the “Polish dance” in the 18th century; the earliest Polish source is a 1772 manuscript collection by Joseph Sychra (with 62 polonaises). The polonaise as a dance form should not be confused with the chorea polonica (i.e. “Polish dance” in Latin) occurring frequently in the Baroque manuscripts of the 17th century. According to many scholars, the chorea polonica has musical characteristics of the krakowiak, not the polonaise.

According to the entry on the polonaise in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, before the end of the 16th century the Polish folk dances that are ancestors of the polonaise were adopted by the lower ranks of the upper classes (gentry and lesser aristocracy). At first they retianed their sung accompaniment, but as these dances became popular among people of higher status, the music was transferred to the instrumentalists who accompanied court dances.

The court polonaise, according to the New Grove entry, “was played by musicians in the galleries of the great reception halls while the assembly, dressed in great splendour, danced it below in processional figures […] In this form it was transformed into the most highbred expression of the Polish national spirit and became in the process the most representative of Polish dances throughout Europe.”

Description

The folk origins of the polonaise are rather distant in contemporary interpretations by folk dance groups. The polonaise is usually danced in costumes of the Polish nobility of the 17th century (the kontusz jackets); some groups present their polonaises in costumes from the period of the Duchy of Warsaw (1811-1814) established by Napoleon before his defeat in 1815 (empire dresses, cavalry uniforms).

The folk antecedents of the polonaise bear names describing their slow tempi – the wolny and powolny (slow); their rotational movements – the obracany (turning), okrągły (round); their walking character – chodzony (walking); and their dignified, impressive moods – the wielki (great). The image on the left is of a polonaise danced by the Krakusy Polish Folk Dance Ensemble in costumes from the Lublin region in east-central Poland.

The dance has been used in formal contexts and during public ceremonies and festivities, particularly at weddings, or, recently, as the first dance of a formal ball. Dancing the polonaise requires a straight, upright posture with no movement of hips, smooth and elegant hand gestures, and the head held high, with pride, as it were. According to Ada Dziewanowska, “the man should display dignity and polite attentiveness not only to his partner, but to others around. The woman should carry herself with grace and a certain timidity” (Dziewanowska, Polish Folk Dances and Songs, p. 478).

The dancers never face each other while holding hands; instead the couples walk arm-in-arm in a procession around the hall, stopping to bow to each other, circling around while holding one hand above eye level, etc. The basic step of the polonaise is adjusted to its triple meter, accenting the first beat in each measure with a longer step (with a slight bending of the knees), and performing two shorter steps with a somewhat straighter, higher position of the body.

There are also options for the couples to move backward, turn, move sideways or dance in place – these variants are useful when the whole procession, directed by the leading couple, has to criss-cross its own path. The cadences of the music are marked with formal bows, each lasting for two measures of the accompaniment. The dance includes special figures to be danced by individual couples, with shifting hands, turns, etc. The group figures include the parting of the couples, promenades, and passing under the elevated hands of the couple at the front of the line. There are many variations in the way the polonaise may be danced. Throughout, it has to maintain its noble, “upright” image, full of dignity and pride.

Costumes

Because this dance has become known as one of the “gentry” or “nobility,” the most appropriate costumes are those from 17th-century Poland which did not yet follow international fashions in clothing, but featured different costumes for members of each social class. The noblemen wore large satin-and-silk ornamental belts (pas słucki), high boots, long overcoats with slit-sleeves lined with fur (kontusz) and fur hats with feathers and jewels. They also shaved their heads, leaving a top bunch of hair, and wore long mustaches.

The noblewomen had their own variants of fur-lined kontusz with long slit-sleeves, and fur hats with jewels. Underneath their jackets, they wore long skirts and high boots. The whole body was covered and the fabric was heavy, lustrous and rich, though without bold patterns or widely contrasting colors. Please note that contemporary Polish folk dance groups usually use shorter skirts than the ones represented in traditional images of the costume. The image to the left portrays a contemporary costume design for the character of a young noblewoman in Stanisław Moniuszko’s national opera, The Haunted Manor – presenting the life of landed nobility in the mid-18th century.

Another choice of costume for the polonaise dates back to the Napoleonic wars and the French/military fashions of the Duchy of Warsaw (a short-lived French protectorate created by Napoleon, 1811-1815). The men wear the uniforms of the Polish legion: tight navy pants with red stripes at the sides, short jackets with decorative button-fastenings and epaulettes, and high square hats with the national emblem on the front.

In some versions of the dance they also carry weapons at their side (szabla); they use them to create a “bridge” above the women’s heads in one figure of the dance (the image is on the left, in a version danced by Krakusy, 1998). The women wear flirtatious and decorative civilian clothes, i.e. the low-cut, short-sleeved, flowing dresses of the Empire period, introduced at the Napoleonic court in France and exported with his rule throughout Europe. Their heads are uncovered, the hair is bound at the top of the head in a French imitation of ancient Greek styles.

The image of the polonaise by Zofia Stryjeńska reproduced above opts for yet another type of the costume; her interpretation dresses the female dancer in the wide-hooped skirt and low-cut shirt with wide sleeves of the pre-revolutionary French court. Notice the woman’s French-style fan and the absence of an elaborate French wig. The man presents a colorful version of a nobleman’s costume. Thus, the artist indicates that the women of the nobility were more likely to follow foreign fashions than the men; apparently in the period before the partitions (late 18th century) Poland was a scene of controversies between the traditionalists and fashionable internationalists who detested both each other costumes and the ideology that these costumes represented. Interestingly, Stryjeńska’s interpretation of the national costume merges the national tradition with international sophistication.

Since the polonaise has folk roots and is widespread throughout the whole country, it is possible to dance it in folk costumes, e.g. from the Kraków area (Polskie Iskry Dance Ensemble), and Beskidy (Podhale Folk Dance Company). These regional versions of the polonaise should have appropriate music. Polish American folk dance groups have used recordings of the polonaises as danced and played by the State Folk Ensembles, Mazowsze and Śląsk.

Music

The early melodies of the old Polish folk dances from which the polonaisewas derived were collected by Oskar Kolberg in the mid-19th century. They consist of short phrases set in triple meter and have no upbeat, but often they feature a two-measure section that is repeated in the middle. This category includes the oldest Polish folk melody, “Oj, chmielu, chmielu” (hops dance) which was sung and danced during the ceremony of the “capping of the bride” at the folk wedding. More stately variants of this melody appeared in the Wielkopolska region (Greater Poland) and in Kujawy.

As the polonaise ceased to be essentially a dance with sung accompaniment, becoming chiefly instrumental, it underwent stylistic and formal changes. In particular, melodies became wider in range and more ornamental. The polonaise was also sometimes performed with a contrasting middle section (a “trio” – borrowed from the formal design of the courtly minuet; the trio first appeared in the polonaises by Michał Kleofas Ogiński), or following the outline of the rondo, with a recurring refrain and contrasting episodes.

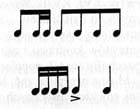

There are two characteristic rhythmic patterns that allow one to recognize the polonaise: (1) the succession of one eighth-note, two sixteenths and four eighth-notes at the opening of the dance (depicted above), and (2) the cadential formula of four sixteenths followed by two quarternotes (depicted below).

Among the first examples to have all the characteristics of the classic polonaise in non-Polish art music (moderate tempo, triple metre, phrases without upbeat, a repeated rhythmic figure and the closing rhythm) are those of Johann Sebastian Bach (French Suite no. 6; Orchestral Suite no. 2). The Germans, for whom the polonaise represented “Polish taste and Polish style,” frequently included the polonaise as a movement in their extended compositions, dance suites, and sonatas (e.g. Georg Telemann, Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, Johann Philipp Kirnberger, Johann Schobert, and Mozart). After 1800, the instrumental polonaise began to be cultivated in Poland by composers, including Michał Kleofas Ogiński (20 polonaises), Wojciech Żywny, Józef Elsner, Józef Kozłowski, and Karol Kurpiński. The popularity of polonaises by some of these men contributed greatly to the spread of the genre throughout Europe, especially in its salon variants (e.g. polonaises composed by German virtuosa pianist, Clara Schumann).

The greatest composer of polonaises in classical music was Fryderyk Chopin, whose works for piano made this dance the musical symbol of Poland and Polishness. Polonaises also appeared in chamber music, concertos and opera, often with the title Polacca. It is interesting to note that during the period of the partitions when Russia occupied one-third of Poland, Russian composers were attracted to the form of the polonaise, which acquired a meaning of “dignity” and “royalty” and was often associated with the appearance of the Tsar, or in general, the rulers. It also appeared in Russian operas as a symbol of the Polish gentry (Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, Tchaikovsky’s Onegin). Moreover, the nostalgic polonaises of Michał Kleofas Ogiński, especially his “Farewell to the Homeland,” became extremely popular in Russia and have been arranged for a variety of instrumental settings.

According to the inventory of Polish dances in American popular music, edited by Aleksander Janta (A History of Nineteenth Century American-Polish Music New York: The Kościuszko Foundation, 1982; p. 148-155), the polonaise appeared in the U.S. in 1815; Janta lists 29 editions of polonaises (including seven by Ogiński), as well as two polonaises attributed to Tadeusz Kościuszko (written in 1792, but of a different authorship).

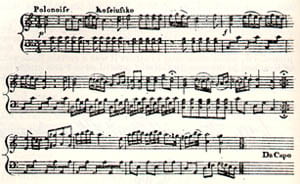

The attribution should not be a surprise: the Polish national dance was supposed to have been created by the Polish national hero (the leader of the Kościuszko Insurrection (1794), unsuccessfully trying to prevent the final division of the country between Prussia, Austria and Russia), and a hero of the American Revolutionary War. A small image of the main part of this polonaise is included above; you may find a full version, with the contrasting Trio, by following the link to the Kosciuszko Polonaise.

While the politically charged mis-attribution of the Kościuszko Polonaise belongs to the history of Polish American music (rather than to the main thread of the history of this dance in Poland), it suggests a particular context for the polonaise. This dance’s elevated political symbolism and its association with the most highly regarded national causes, as well as its own noble and stately character, assured its reception as the primary national dance of Poland.

Sources of Materials

- Burhardt, Stefan. Polonez. Katalog Tematyczny (Polonaise: Thematic Catalogue), 3 vols. Kraków: PWM Edition, 1976.

- Dziewanowska, Ada. Polish Folk Dances & Songs: A Step by Step Guide. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1999.

- Janta, Aleksander. A History of Nineteenth Century American-Polish Music New York: The Kosciuszko Foundation, 1982.

- “Polonez,” entry in Encyklopedia Muzyki PWN Warszawa: PWN, 1994.

- “Polonaise,” entry by Józef M. Reiss, and Maurice J.E. Brown in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, vol. 15. Stanley Sadie, ed. London: McMillan, 1980.

- Trochimczyk, Maja. “Dance as a National Symbol: Polish Dance in Southern California” Project for Southern California Studies Center at USC, August 2000.

Illustrations from Polish folk art (straw cutouts); Zofia Stryjeńska’s 1927 “Polonez” image; photographs from PMRC Collection and from archival material gathered for M.A. Harley’s Polish Dance in Southern California project.