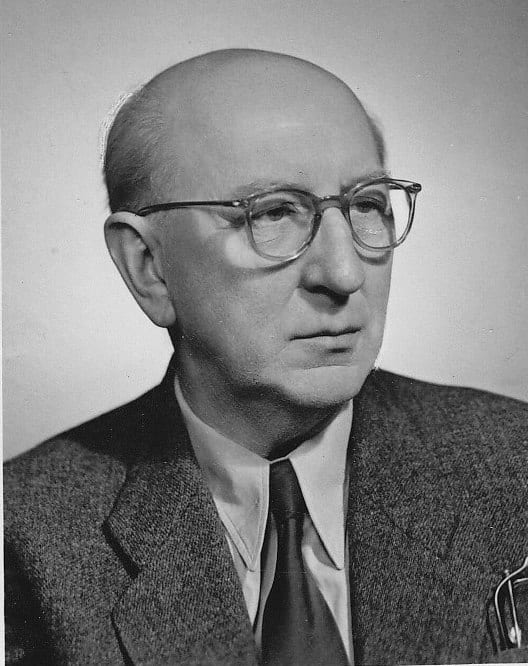

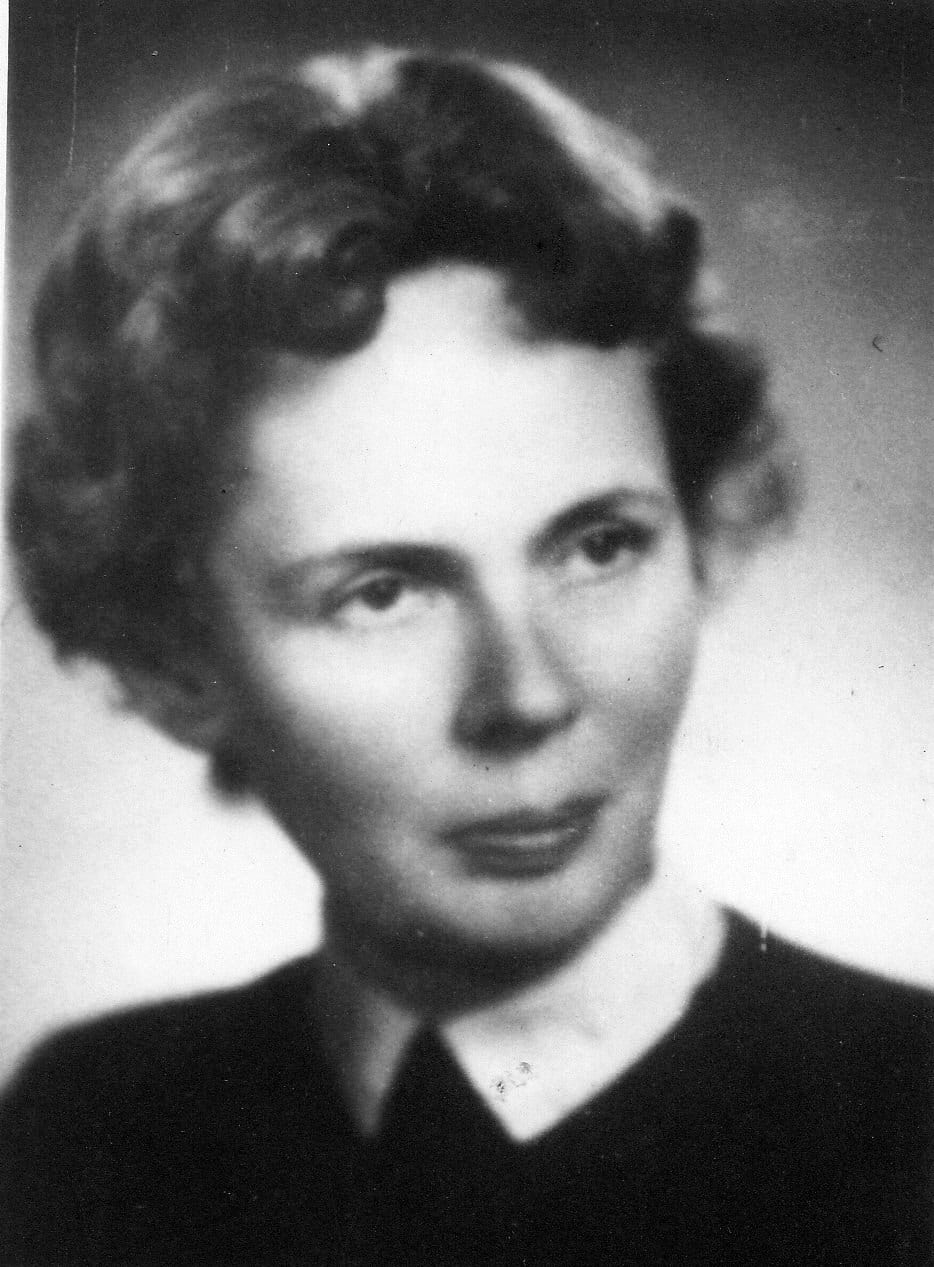

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the 2020 Paderewski Lecture was conducted as an interview via Zoom on 22 August 2020, and broadcast to the worldwide public via USC ThorntonLIVE on 10 October 2020. The interview, transcribed below, features composer Krzysztof Meyer (KM) and his wife, musicologist Danuta Gwizdalanka (DG), in conversation with PMC director Marek Zebrowski (MZ).

MZ: It’s August 22, 2020 and we are conducting an interview that will be a part of the annual Polish Music Center Paderewski Lecture-Recital presentations. We planned it with our distinguished guest, Krzysztof Meyer, already in 2007 but, unfortunately, it did not work out. In any case, due to this year’s pandemic and travel restrictions we welcome Krzysztof Meyer virtually for this video interview today. We will talk about his musical career, composing, and teaching music. Let’s begin with a short quote…

The task of a composer is to write music, not to talk about it… The musical content of a work is never translatable into words. Every listener absorbs music in a slightly different way, so words about music are in danger of being incompatible—even if only partially— with the impressions of individual listeners. Besides, making comments about one’s own music inevitably lacks objectivity and often results in a distorted picture, just the kind a given composer wishes not to paint. Some would say that by talking about his music, the composer guides his listeners; others will hold that the composer manipulates his audience…

KM: I am not sure if we must discuss my music, but talking about music in general is a pleasure. Although I do not know whose quote it was, and who said so, I completely agree.[1] I think that self-contained music is good and interesting music that can be beautiful and, in such a case, no comments are needed. Besides, if comments were to be made by composers, one has to take everything with a grain of salt because the composers’ statements are often misleading; they can be at odds with truth and result from the composer’s mood on a given day. That is why I am being very careful here—I know my colleagues. I have known many great and not so great composers in my life, younger and older, all different kinds. And all of them told various tales about what they wrote, how they wrote, what their music expresses, what technique was used; these are pleasant anecdotes that amuse us and are fun to recall, but they don’t bring any intrinsic value to the discussion…

MZ: Let us begin with the biographical information. It might be best to start with your pianist grandmother…

KM: Certainly, because my grandmother was the only musician in my family. My parents were doctors. Grandmother was a pianist. She was my father’s mother and she cultivated the 19th century tradition of house concerts. As a small kid—I was four or five years old when my grandmother died—I had a chance to discover chamber music, including works by Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Dvořak, or Brahms. These were really the first compositions I heard in my life. It was not opera or symphonies at a concert halls, but chamber music. Since chamber music is my favorite genre, perhaps that experience influenced me so deeply. As a composer I really wrote a lot of chamber music and I feel a particular kinship to chamber music making; I played a lot of chamber music, certainly not only my own, and that’s a genre that’s very close to me.

MEYER AS STUDENT

MZ: In your music studies and early career you encountered incredible musicians, from Stanisław Wiechowicz, Krzysztof Penderecki, and Nadia Boulanger—who were your professors—to others who were your friends, like Dmitri Shostakovich, and other giants of 20th century music.

MZ: In your music studies and early career you encountered incredible musicians, from Stanisław Wiechowicz, Krzysztof Penderecki, and Nadia Boulanger—who were your professors—to others who were your friends, like Dmitri Shostakovich, and other giants of 20th century music.

KM: Yes, it is true. I had contacts with phenomenal musicians who, in a sense, were my professors, even if in the final analysis, it wasn’t quite like that. Not everything worked out as planned. Why? My piano teacher, the sister of Jan Ekier, was a great musician and pedagogue; she quickly noticed I was seriously interested in composing music and she decided to introduce me to Stanisław Wiechowicz. I was 11 years old. Stanisław Wiechowicz was then 61. It was a huge age difference. He listened to a few of my works and decided—shall we say—to take me under his wing.

He did so very sensibly by prescribing a solid course of harmony, and later a study of counterpoint with his assistant, Maria Fieldorf, whom I will never forget. A niece of General “Nil” Fieldorf, she taught me the basics of harmony, counterpoint, fugue, and later even of twelve-tone technique. But the so-called composition lessons with Stanisław Wiechowicz were held once a month or every two months, always on Sundays in his flat. I must say that I was quite young and these were my first steps in composition, the very first pieces I wrote. Stanisław Wiechowicz approached them very warmly, but he could not convey to me what he could share with his students, since I was too young to understand. And later, after passing my high-school exams and after I began my studies, Wiechowicz became quite ill and died shortly thereafter. So, in a way, my studies with Wiechowicz were incomplete, unfinished…

Krzysztof Penderecki was my second teacher and that is another story. Krzysztof Penderecki had just begun his great career—he was writing his Passion at that time. He simply had no time to teach, no time to meet with students. The two years of studies that I officially had with him were limited to four meetings; he had no idea what I was writing for my graduation—what would be my final diploma work. One week before the final exam he asked me, “Are your working on something? Composing something?” It was a very nice meeting, but it really didn’t give me much. Well, it gave me something, in a general sense—Penderecki was a great connoisseur of literature and gave me books to read. I remember his fascination with Andrzejewski at that time—Jerzy Andrzejewski was a very important writer for him.[2] He also talked a lot about architecture, was ecstatic about Vitruvius, so these too were very interesting meetings. But when it comes to learning composition, there was nothing there. Let’s be clear—there was nothing there besides very nice meetings and my affection and respect. However, I still could say in my biography that I am a student of Krzysztof Penderecki.

My next professor did not work out either. Why? Nadia Boulanger came to Kraków.[3] She awed all of us with her memory, professionalism, and knowledge of music, from Perotin to modern times. I showed her my First Piano Sonata. She judged it worthy and said, “You must come to my summer school in Fontainebleau.” There was an American conservatory there. “I would like you to be one of my students.” Fine. I finally got there after some delays and I lucked out because in those days it was difficult to get a Polish passport and French visa. I was 21 and Nadia Boulanger was 77. So there couldn’t be much in common between us in the sense that she would be correcting my works or telling me how to make them better, because the musical language I used at that time was completely alien to her and she had basically very little to say about it. But, but! She had this extraordinary gift. She could instill each student with great sensitivity to sound, to music… She always looked for what’s in-between the notes, not only in the score itself. She simply taught her students how to understand and experience music. I do not know of any other human being with such a gift of convincing and identifying the soul of a musical work. By this measure, I truly learned a lot from Nadia Boulanger, but it was not a study of composition.

Immediately after graduating from the State Higher School of Music—that’s how Kraków Music Academy was called at that time—in the class of Krzysztof Penderecki (who first heard my composition during the final exam), I had a debut concert at the Warsaw Autumn Festival. After this debut, where my First String Quartet was played, the great Lutosławski approached me and said, “I’m very interested in what you’re doing. Wouldn’t you like at some point to visit me in Warsaw and show me your latest work?” I must say I was speechless… First, because he came to me (I didn’t ask him); second because of his proposition; and third because Witold Lutosławski, his stature and his music were for me even then very important and very stimulating for my imagination.

I went to see him for the first time about two months after Warsaw Autumn in November and showed him my compositions. He took them very seriously and was very encouraging, but that is not the point. At that time he gave me a lot of purely technical solutions for composing. So that when on that rainy November night I left his flat, I had an epiphany: “I finally met a real composition teacher with whom I could study.” Of course he was meeting all kinds of young composers, but this was a very intermittent education. Nonetheless, I must say that—in my development as a composer—to nobody else I owe as much as I do to Witold Lutosławski. I will also add that his style and techniques were not something I identified with. I admired and respected them and realized their importance, but it was not something I wanted to join and follow. There may have been some influence, but I think and hope that it was rather short-term. Generally, this contact with such a fascinating intellect—because it was truly a captivating mind—and a person who is not only a musician but a human being and a humanist, someone interested in life, history, politics, fine arts, and the situation in Poland, really gave me a lot. A confirmation of this fact was that, when martial law was declared and life in Poland had stopped, a few days after Jaruzelski saddled us with the nightmare government, I boarded a train and went to see Witold Lutosławski simply for a few days of hope for the future.[4] And I must say that I received this hope.

This the history about my professors… However, returning to your original question, they were not really my teachers. Lutosławski was one of them to the greatest degree, but even then not completely, since I was already developed as a composer and knew which direction to take. He did not suggest new solutions or the direction to follow but rather tried to improve and advance whatever inspired me. In a way, I may have been too old to study. Perhaps I should have started at 18 or 19 at the latest, but I was already 22-23 years old. Three years later Lutosławski told me, “Now I think that you’ve learned enough from me, so let’s keep in close touch and keep meeting, but not on the basis of master and student. And let’s use first names when we talk.” That’s when I was completely dumbstruck.

MZ: We are talking about the mid-1960s—you are now a very promising young composer but you also appear as pianist, you perform as a chamber musician in the MW2 Ensemble. I would like you to address the role of piano in 20th century music, in particular in works by Bartók, Messiaen, Ligeti, and the European avant-garde of that era…

KM: When it comes to the 1960s, I would say that, in music written at that time, the role of the piano was rather meager. The piano was treated as a source of acoustical effects that had nothing to do with the piano legacy. I played all kinds of music—John Cage, Sylvano Bussotti and Louis Andriessen—but it jarred somewhat with my idea of what piano playing should be like—in the sense of works written by the composers you mentioned, like Bela Bartók or Olivier Messaien. That was not what it should be… Besides, I performed with the MW2 Ensemble only for three years, and didn’t have much time for it even if working with the group was very interesting for me due to the fact that I became acquainted with a lot of modern music. At my age at that time, I still needed to see what’s going on, listen and discover in order to educate myself. So, this wasn’t a waste of time. At the same time I also wrote for piano and unfortunately departed a little from the tradition I was close to, but when you are in your 20s, you search for things… And this searching benefited me to a degree; however when I look at these works today—works that are performed and recorded—it’s not that I’m ashamed of them, but I see how little I knew at that time.

As far as my favorite composers, it wasn’t the avant-garde, like Karlheinz Stockhausen (whose music I knew), or Pierre Boulez, but there were a few Boulez’ pieces that fascinated me and impressed me deeply, like Pli selon pli, for example. But I had one composer who represented absolutely everything for me in terms of approaching sound and form… it was Bela Bartók. I was brought up on Bartók thanks exclusively to my piano teacher, Ms. [Halina] Ekier. I played almost everything by Bartók for her, because I asked her to study and play Bartók. For me Bartók was—and still is—an example of certain uncompromised approach, looking for new structures, of independence, and individuality of the kind that is free of all influences. The kind of artistic stand that he espoused had always impressed me deeply.

MZ: How about Messiaen, his piano works, and Ligeti?

KM: Ligeti was much later; he came out with his Etudes only in the 1980s. I knew Messiaen, of course, but this was not my world. I certainly valued it highly, considered it important, and was convinced that it was a chapter in itself in the history of piano and history of contemporary music. But it wasn’t my world. I knew almost all of Messiaen’s works and there are many of them, starting with Vingt Regards, that I consider phenomenal piano compositions. I would say I was familiar with all of his piano music, but it wasn’t a path I was willing to take.

MEYER AS TEACHER

MZ: At this point, we are coming to the heart of our interview today and to the fundamental idea of the Polish Music Center’s Paderewski Lecture. Let’s talk about your composing methods and also about teaching composition. Based on your experience with Lutosławski, Wiechowicz, Penderecki and Nadia Boulanger is it at all possible to teach composition?

KM: Let’s begin with teaching composition. I say “teaching” in quotes because there really isn’t anything like “teaching composition.” This is because either someone has imagination, talent and potential that can amount to something, or he does not and, in such a case, even if Beethoven were to teach such a student, the results would be nil.

The professor’s task is to recognize the kind of talent a young person has and skillfully guide its growth. It is a very complex subject because each talent is different. There are no comparisons here and no specific experience that would have been helpful in working with the next apprentice. It is simply a new experience each time, also for me.

Of course there is a whole spectrum of topics, a range of problems that touch every aspiring artist. They pertain, for starters, to such issues as notation: how to write it down so that the work is not only playable, but also explicitly notated. I often gave all kinds of assignments on learning the properties of instruments. One writes differently for each instrument and students must know that certain effects or techniques are possible and simple, but on other instruments clearly impossible to perform. It all depends on teaching. And, in addition to what I did—and this was influenced by Nadia Boulanger—I always had on hand important contemporary music scores that I suggested to my students. They were of course matched to what they were working on and what kept them busy. If someone was fascinated by percussion, for example, I clearly wouldn’t show them Messiaen’s piano pieces, because it would make no sense. The choice of repertoire matched to the interest of the young apprentice always seemed very important to me.

Generally speaking, at this moment I could bring up all kinds of stories and amusing anecdotes connected to teaching composition. I had many classes of international students and, in each class, these students represented certain cultures and traditions. Contemporary music was something quite different for someone from Argentina (I had a very gifted student from there), and for someone from South Korea who represented a different world. I had students from Russia, Bulgaria, and from all kinds of cultures and nationalities. It was also a challenge for me to somehow learn their culture and learn their traditions. My classes expanded their sensitivities in a way and opened a completely different world that had no connection with their past.

MEYER AS COMPOSER

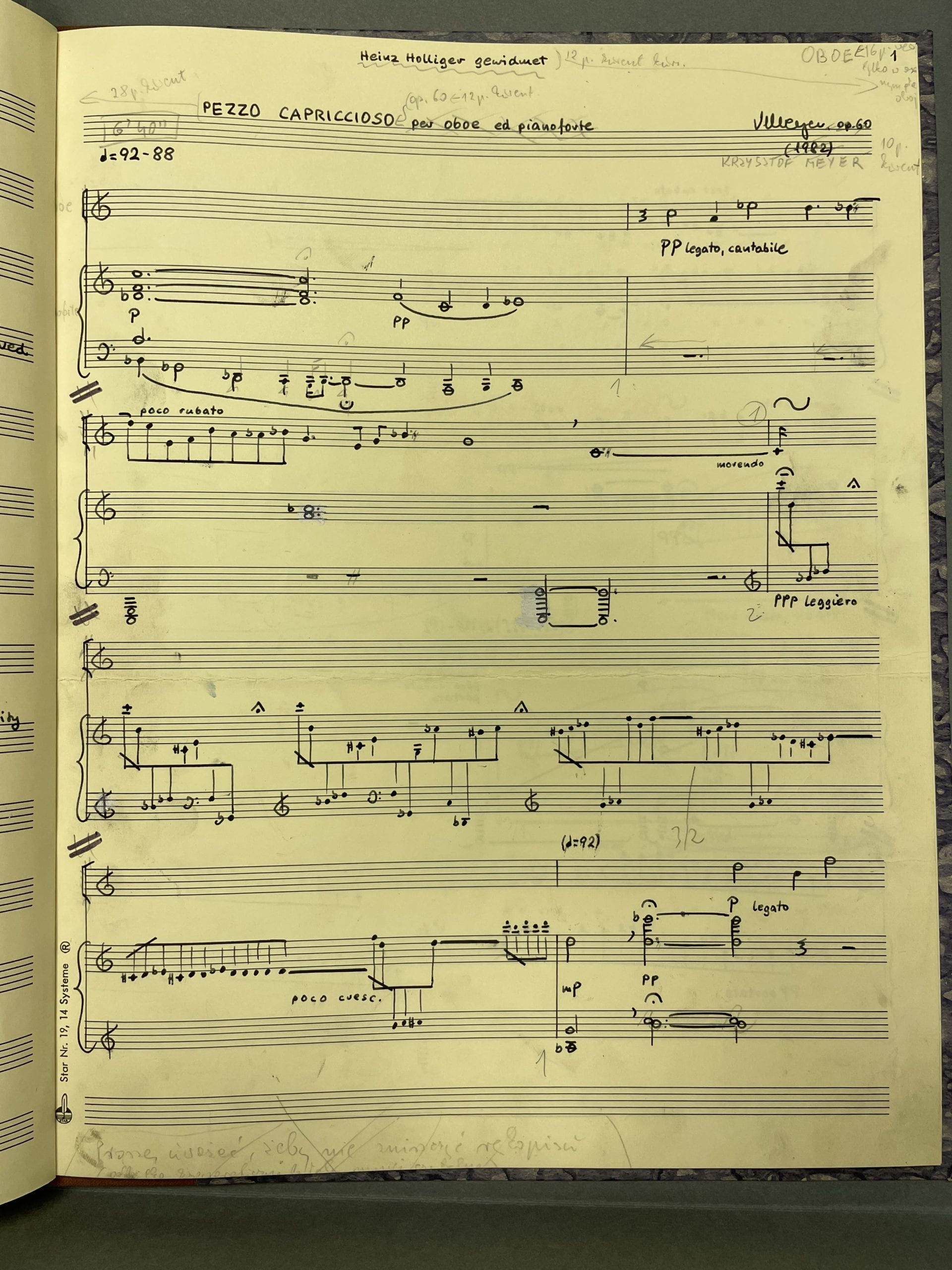

MZ: Let us now focus on your composing methods and—at the same time—maybe you could say something about the manuscripts we have at the Polish Music Center. Because we have a gorgeous manuscript of your Cyberiada, Piano Concerto, String Quartet No. 10, and Pezzo capriccioso…

KM: What can I say about these manuscripts? It’s great that you have them because my house is quite a mess and manuscripts sometimes get lost and I’m not sure if I still have them or not. I need to put them in order at some point. Maybe if I come to visit you, I’ll again bring something. Being a rather diligent person—not too diligent but working steadily for over 60 years—a big stack of papers has accumulated. If someone is happy to have them—go ahead! But… what I could say about the manuscripts is really not that interesting.

It’s because I write clear, calligraphic copy and toss away all sketches, so that nobody knows the path I’ve taken to reach the final destination. In this respect Brahms is my example. There are no Brahms’s sketches. I like that very much. Who really cares how I wrote a given work? The final result is what counts—it’s my work and my score. As I said, these manuscripts are basically uninteresting… With Penderecki you have a lot of color marks—red, blue, and green markers, thick strokes all over… It looks very attractive. My scores are nothing like that. Everybody can actually be disappointed. I must say that my publisher—Hans Sikorski in Hamburg—thinks that engraving my scores isn’t worth the trouble since the printed version of computer-generated score is quite impersonal. Although that’s what the publisher says, I’m not quite sure—maybe he wants to save money. But if the notation is very clear and readable, it also testifies to the composer’s character and to his approach to composing, so that part of my scores are published as facsimiles. With the exception of chamber music and—interestingly—with the exception of piano reduction scores for all of the instrumental concertos, I wrote the reductions which Sikorski published. And these are Komputer gesetzt – or, as you’d say, entered into a computer and published.

Returning to your question about how I compose, I’ll give a banal answer. Regularly! Each day I begin to work between 9 and 10 in the morning and work until 2 p.m. with a small coffee break. These are my sacred hours. I do not call anyone; I do not talk to anyone. I only meet my wife for coffee and that’s it. This is extremely precious for me, because I have it fresh in my mind, I remember what I did a day before—it is, I could say, a continuation of the process. And in the afternoon it’s the corrections or maybe attending to other business. Usually, I do not write in the afternoon. That’s how I could write so much in my life. That is also why I always taught in Kraków and Cologne in the afternoons in order not to ruin my best morning hours that I always devote to composing.

I also know that this is not exactly what you asked for. I compose when I have a complete image of the work in my mind. Not to the very last detail—that wouldn’t be true—but I know how it will go, what the dramatic structure will be, what colors I’ll use, and what rhythmic structure I’ll employ. All of this has to be set first in my imagination, and if it is, I begin to write. Even then, the writing goes rather laboriously, so it’s not like I’m writing down what’s in my head, but I look for better solutions, more interesting ways of putting my musical ideas across. It is a long process and I’m very suspicious of myself if something comes along too quickly.

MZ: So here’s one more question, somewhat related to the subject. You worked with many outstanding soloists…

KM: Aurèle Nicolet (R), Lothar Faber, Heinz Holliger (R), Edward Brunner, trumpeter Timofei Dokshizer, violinist Dmitry Sitkovetsky…. And a bunch of excellent cellists: Ivan Monighetti (below, L), David Geringas, Boris Pergamenschikow (below, R), Lynn Harrell… All of them are a constellation of marvelous musicians, thanks to whom I have learned a lot. They also were—indirectly—my teachers, because that’s how I found out about various details, tiny ones, about how to better write for a given instrument. It may be quite pleasant to give the score and this score is ready for performing—there aren’t any questions or doubts. It’s amusing sometimes and here I have to brag—sometimes one has to blow one’s own trumpet. I wrote a string quartet; it was Quartet No. 12 and it was world-premiered by an ensemble in Weimar, Germany. Before the first rehearsal I met with a violinist. We were sitting, drinking coffee, looking at the score and he was asking me all kinds of questions. Finally, he said, “But, Maestro… Why do you want this played on the A string here, rather then the E string? As a violin player, you know quite well, that it’ll sound brighter if it’s the E string.” I interrupted him, saying, “But I don’t play violin, and never have.” “Well, well, what do you know? Don’t tell me tales. I know it when I see it; I know who can play and who cannot!” It was a funny story. A moment later I added, “But you know, I wanted a darker sound here.”

KM: Here is funny interview story about a TV interview with Penderecki. He wrote something and it was an occasion for a studio meeting—Penderecki with a group of musicians. We entered… Penderecki comes in, then we follow—there was Wanda Wiłkomirska, there was Stenia Woytowicz, and a few others. And the master of ceremonies says, “So… we’re really delighted to welcome Maestro Krzysztof Penderecki. We also welcome a group of excellent musicians (he mentioned all of our names). The first question I wanted to ask Mr. Penderecki is, “Which of your compositions you consider the most important?” So Penderecki says, “Well, certainly my larger vocal-instrumental works, like the Passion, Utrenia…” At that moment we hear a voice, “We’re very sorry. We have some technical problems and need to start over.” All right, fine. The ceremonial entry is repeated. Penderecki comes in. We follow and sit down. There is a greeting and a question. “The first question which I wanted to ask Maestro Penderecki is… which of your compositions you consider most important?” “Well, certainly, it’s my chamber music,” replied the Maestro! You can see that in interviews composers sometimes will give you completely different answers to the same questions.

MZ: What are your latest projects and opuses on which you work each morning?

KM: This is a difficult question and I am a superstitious person. If I say now what I am working on, it’ll certainly fail. And I want this project to succeed, because it is a wonderful work… so, let’s move on.

MZ: No problem! Let’s talk a little more about the quote that we’ve started this interview with, a quote about the reception of contemporary music nowadays. Who should be—and who actually are—the consumers? Let’s also discuss the quote by Quintilian that “educated consumers understand art but the more primitive ones can only enjoy the pleasures that art provides.” So, a few words about the audiences, the ideal audience for your compositions, and the ideal audience for contemporary music. Because we mostly listen to old music, written 50, 100, 200, 300 years ago…

KM: Yes, unfortunately that is so. What can be said about the audiences? Something like an ideal or very good consumer does not really exist… This is a single human being—and one will react well, the other badly. I have an example… Some time ago my Clarinet Quintet was given a superb world premiere by the now deceased Eduard Brunner and the Wilanów String Quartet. It was at a festival in Ulm, organized by Pierre Boulez at that time. The musicians played wonderfully and the reception was excellent. We came out on stage many times, taking bows, and were almost forced to play an encore. The same concert was repeated the next day—with the same performers—in Mannheim. Once again, my Clarinet Quintet was performed just as well as in Ulm. Now imagine this: as the piece ended the performers had to leave the stage with the audience practically silent. So, here’s a question: “Does it mean that I wrote a good piece (because it got a huge applause in Ulm), or was it a terrible piece (because almost nobody applauded in Mannheim)?” Was it a good performance—just like it was received in Ulm… One cannot really say whether it was a good reception and who is or is not a good consumer.

My ideal listener would be someone who approaches contemporary and older music with the same degree of engagement. Someone who would be happy to hear for the “nth time” a Beethoven symphony, or a work, say, like a Beethoven Sonata and Ligeti’s Etudes. I think that this would be really desired. It is rare, but of course, possible, and it happens… A lot certainly depends on the performer. Many times I had truly fantastic public reception, but it was due in large measure to fantastic performers whom we’ve already mentioned.

So, the answer isn’t simple—it isn’t that contemporary music is less welcome, that audiences really prefer listening to older music… It isn’t so. But a certain reticence towards contemporary music is due, I’d say, to the composers’ fault. It is because things we listen to have been sorted out by time and what is created today is a salad, or a dump, where we have interesting compositions and mostly bad works. This is a huge topic for another discussion. In my mind, the degree of professionalism has diminished significantly. Everything that happened during the early Warsaw Autumn, Semaines Musicales concerts, or the earlier Donaueschingen festivals was on a much higher technical level, when you consider compositional techniques and the composers’ imagination, than it is today. Why this is so—is a long story. But it is so, and this fact also doesn’t contribute to a welcoming attitude of the public towards these works.

MEYER AS AUTHOR

MZ: Moving on to another topic, let’s open this part of the interview with the discussion of your book about Shostakovich—it was a great hit that was translated to dozens of languages…

KM: There are translations, of course, but that is certainly an exaggeration. I need to begin by saying that I am not a music writer nor a musicologist. My book about Shostakovich really was a form of my gratitude to a man who was very close to me, who devoted some of his time to our meetings and correspondence. I was in touch with him for over a dozen years, until his death. What I received from him was, primarily, a lot of purely musical impressions and, at the same time, it was a kind of heartfelt, purely human friendship that I of course treasured. So I thought that I needed to react to what I had received from him. “To reciprocate” is such an ugly word, isn’t it? But I thought that, after his death, I’ll write a book that could possibly show more truth than what was known about Shostakovich—about what was distorted both locally and in the West and set aside all that was fictitious. I simply tried to straighten a few things out and that is why I wrote Shostakovich and His Times. It contains a lot about the political and social environment in which he had to live. So, I wrote this book and it was published in various languages. Now, together with my wife, we wrote a new book!

Danuta Gwizdalanka: Ha! But was it just the two of us? Many Russian authors found documents that became available only in the 1990s. They were published as books or articles and some were accessible online. So, it was a very interesting challenge based, mainly, on unwinding lots of things that had to be disentangled. At the same time it turned out that a lot has happened in the Russian music world, since nobody had any idea, including those directly involved. Only when the minutes of various meetings with composers appeared, the truth came out. I will give one typical example relating to the famous congress when the Soviet Composers’ Union was founded. When one reads the official documents and all of the books published on the subject (including yours at the beginning), one finds that there was a lot of cheering, that everybody agreed on everything, including the so-called critiques and self-critiques. My God! What a well-behaved Composers’ Union! But after studying various documents compiled for the Soviet government’s use by the same government’s representatives, it turned out that—although the composers didn’t riot—they did not vote as directed, they didn’t want to sit through meetings, and assembled in the corridors robustly criticizing everything that went on. As a result, the picture is completely different from the one portrayed in every publication, including Volkov’s.[5] Interestingly, Stalin was absent in those documents. The composers feuded with each other and Stalin had no idea what went on.

MZ: This is very interesting news. When will this book be published?

KM & DG: Well! Please ask Dr. Cichy. Polish Music Publishers has it in their hands; ask them.

MZ: Thank you! We’ll follow up on this suggestion, so stay tuned! But you also wrote books about Lutosławski, Szymanowski… Tell us something about working together…

KM: I did not write about Szymanowski. Only my wife worked on this project.

DG: Poor fellow… for two or three years the two of have lived with Szymanowski. What a triangle! Since we always exchange information and the understanding among us both, the subject of Szymanowski was constantly present in our discussions.

KM: But both of us really wrote about Lutosławski… Why? I have to say that the motivation was mine (it was my idea to write a big, two-volume book on Lutosławski), and my decision was similar to the one I took when writing a book about Shostakovich. It was a kind of reciprocity for Lutosławski’s friendship. I knew Lutosławski for 29 years, and Shostakovich for 14.

DG: When Lutosławski died, you said, “I really should write a small book in order to immortalize our relationship.” And this small book turned out to be in two volumes!

KM & DG: For the Lutosławski book our job was to find documents and witnesses. We were fortunate to find Lutosławski’s high school friends at the very last moment before they passed away. Still, we were led astray anyway in many cases and this insight became clear years later. Lutosławski never talked about the fact that he was really brought up by his mother’s family—the Olszewskis—and his grandmother! But everybody was asking about the Lutosławskis, because a lot is known about them. This became clear by accident only a few years ago…

MZ: Will there finally be a shorter, one-volume version of the Lutosławski text, suitable for translation into English?

KM &DG: Yes. There is also a shorter German version. The English version is ready, but there is no partner. That version omits certain details that are interesting only to a Polish reader, and adds certain information that may be of interest to readers outside Poland. This version is ready and has been published in German. A Russian version also exists; it wasn’t published but it’s available, since someone copied it and posted it online. Again, the English version is ready, but to publish it we need a partner.

MZ: Could you tell me about ways of writing together? Do you write at the same or at different times? Are you working on the same or different floors?

KM & DG: No! No! We are two floors apart! Two different levels and two different styles. Also a different world view. There are a few convergence points and basically that’s very good, since we are reaching for some kind of truth, converging on truth using this kind of an approach. My wife Danuta is a musicologist, I am not. I can analyze scores from the composer’s point of view—something I have done alone in respect to Lutosławski’s opus. My wife was more focused on the biographical side, so we had a very clear, very precise division of labor. That’s how it happened and it took three years…

DG: We understand each other, but each of us has a different approach, just as you said. And then we read each other’s texts. If, for example, there is an analytical fragment about music and I’m reading it and say, “Well, we’ve got problems,” that’s a high warning that a normal reader won’t get it and we have to fix it somehow. When I, in turn, do something with history or psychology and hear from Krzysztof, “You know, this is too much of a shortcut—it has to be developed,” well, we develop it.

MZ: Are there any other subjects you wanted to touch upon in this interview, something to close it?

KM: It is your call. Certainly, there are plenty of subjects! If you really wanted, this could be a kind of introduction to our conversations. Maybe I’m joking, but there are plenty of subjects since I’ve gone through life—and am still going—enjoying contacts with performers, conductors, musicologists, audiences, with different cultures, countries, tons of stories and anecdotes and amazing reminiscences that lend color. In the profession I have practiced for so many years, there is one magnificent thing: the role of chance. Many times in my life chance has decided that my activities went in a completely different, unforeseen direction that I could never have expected. I will say this: We were once vacationing in Switzerland. We were sightseeing and the weather was great. It rained only one day. So we were in a place where we stayed and my wife found a newspaper.

DG: I started reading it—you were composing, of course. As I was reading the paper, I became very surprised with a great number of “help wanted” ads. I was taught all my life that there is a widespread unemployment in the West. And I thought, “What’s going on?”

KM: We looked further and found that Berlin and Cologne were looking for a professor of composition. That’s how we ended up there… So, I wrote and sent my resume, and was invited in for a rehearsal… But if it didn’t rain that day, we would have been sightseeing in another canton and we wouldn’t have ended up in Cologne.

DG: You need to be ready for all chance events. The mere fact that it rained did not lead into anything…

KM: Sure, but rain made it happen… This is one of a dozen examples showing what chance can bring in life…

MZ: In such a case, I’d very much like to continue the conversation, just like we had it today, but in person, in Los Angeles. Thank you for all anecdotes and stories about other composers, friends, performers, and generally about music. Music that we love and especially your music. We may still discuss your latest scores in greater detail, some of which could perhaps join the Polish Music Center collection. We would like that a lot. Thank you.

KM & DG: Thank you; thank you very much!

Notes:

[1] This quote actually comes from the opening of Krzysztof Meyer’s 2007 Paderewski Lecture that he was not able to deliver in person due to the U.S. Immigration Office refusing to issue his visitor’s visa. [Ed.]

[2] Jerzy Andrzejewski (1909-1983) was a prolific Polish author whose novels Ashes and Diamonds and Holy Week were adapted into films by the Oscar-winning Polish director, Andrzej Wajda. [Ed.]

[3] Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979) was perhaps the most famous teacher for all of the most prominent 20th century composers. [Ed.]

[4] Wojciech Jaruzelski (1923-2014) was a Polish general and a leader of the military government after Solidarity Trade Union was abolished and martial law was declared in Poland in December of 1981. [Ed.]

[5] A reference to Testimony, a controversial 1979 biography of Shostakovich by Solomon Volkov (b. 1944). [Ed.]