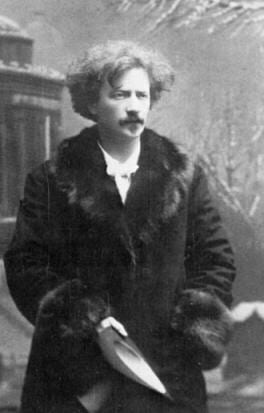

6 November 1860, Kuryłówka — 29 June 1941, New York City

Biography

Who was Paderewski?

Born in Kuryłówka (now Kurilivka, Ukraine), Ignacy Jan Paderewski was a virtuoso pianist, a notable composer, a remarkably successful politician and an exceptionally generous philanthropist. Although discouraged by his teachers from becoming a pianist, his brilliant artistic career was launched with his spectacular 1888 Paris debut, after which Paderewski literally swept the world with his playing and his dynamic personality.

In 1932 American president Franklin Delano Roosevelt called him a “Modern Immortal” and, two years later in a book written by Charles Phillips, The Story of a Modern Immortal, we read in the introduction that, “It is difficult to write of Paderewski without emotion. Statesman, orator, pianist and composer, he is a superlative man, and his genius transcends that of anyone I have ever known. Those of us who love Poland are glad that she can claim him as a son, but let her always remember that Ignace Jan Paderewski belongs to all mankind.”

Undoubtedly Paderewski was a one in a century phenomenon–an artist of a distinctly pronounced individuality who was widely acknowledged as genius and a formidable intellectual. A statesman par excellence and a skillful public speaker fluent in seven languages, he was a great Polish patriot who was essential in securing Poland independence after World War I.

The famous virtuoso…

He was befriended and adored not only by the most prominent people of his time, but by people from all walks of life. He traveled all over the world from Africa to Australia and across the European continent; crossing the Atlantic more than thirty times. He gave more than 1500 concerts in the U.S., appearing in every state and drawing the largest crowds in history at a time when the solo recital was still in its infancy. Up until then, all artists appeared with others during a recital to give it interest and variety. He was the first to give a recital alone in the newly built Carnegie Hall in New York City, which held almost 3,000 people. He was such a great showman and drawing card that he could be his own rival, as the newspaper headlines raved in 1902. While his opera was being performed at the Met, Paderewski was playing a recital in Carnegie Hall, and both places were filled to overflowing.

He traveled throughout the U.S. in his own private railroad cars with several pianos, not only for practical purposes, but also because he enjoyed living in a grand style. Whole towns would go out to meet him and escort him to the concert hall or would just come to see his train pass by. Trainloads of people would come in from outlying towns to hear him play. Once when a train from Montana was delayed by a snowstorm he waited for the arriving audience before beginning his recital. His audience did the same whenever he was delayed. They could not get enough of his playing and would refuse to go home even hours past the end of his program. He gladly continued to play encore after encore.

Why was he so popular? One reason was his magnificent physical appearance. His long, red hair inspired admiration and awe. The term “long haired music” may have originated with him. Many musicians tried to emulate him, wearing the familiar top hat, long coat and long hair. Candies, toys and soaps were designed with him in mind. One Christmas toy was that of a little man with a black frock coat, white bow tie and a huge head of flame-colored hair sitting at a piano. At the turn of a screw the little man’s hands rushed up and down the keyboard while his head shook violently.

Paderewski’s appearance, along with his blend of aristocratic refinement and power over the masses, was certainly what the time required. However, the main reason for his popularity was his magnificent playing. Each recital was a spiritual event. He excelled in the art of producing beautiful and varied tone colors never before dreamt of in a piano–from the lightest and most sparkling to the most violent extremes, which sounded almost orchestral. He was known for having perfected the touch that could literally make the piano sing. His pedaling was also perfect and his musical renderings, no matter how different, were the fruit of profound and serious study.

Even though he was criticized by some for his excessive use of tempo rubato and for vertically uneven playing of chords, such expressive devices were common to the Romantic era pianists of whom he was one of the last. Some musicians acclaimed him as the greatest Bach exponent of his time. Some of his Beethoven interpretations cannot be surpassed. He was considered the best Chopin player of his time and no one could play the Liszt Hungarian Rhapsodies as he did. He recorded some of his standard repertoire and can even be seen performing it in the 1937 film Moonlight Sonata, where Paderewski also has a speaking role!

Admired for his music…

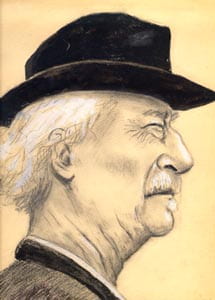

He inspired artists, poets, painters and composers. The most famous portrait of him is by Sir Edward Byrne-Jones, who accidentally passed him on the street one day. He went home to explain that he had seen an archangel and started sketching from memory. A few days later Paderewski was brought into his studio whereupon the artist shouted, ” You are my archangel!” In two hours he completed the portrait.

Richard Gilder, editor of Century Magazine, composed a poem, “How Paderewski Plays,” and American poet John H. Finley addressed the following lines to him:

Your touch has been transmuted into sound

As perfect as an orchid or a rose,

True as a mathematic formula

Yet full of color as an evening sky.

But there’s a symphony that you’ve evoked

From out of the hearts of men, more wonderful

Than you have played upon your instrument…

Composers dedicated their music to Paderewski. Sir Edward Elgar used various motives taken from Paderewski’s Fantaisie Polonaise in his symphonic work, Polonia and Camille Saint-Saëns dedicated a Polonaise for Two Pianos to him.

Although Paderewski aspired to be a great composer and considered it his most enjoyable pursuit, he devoted only a relatively small portion of his energies to it. He composed several dozen works, which include an opera, a symphony, two large scale compositions for piano and orchestra, a violin and piano sonata, several beautiful songs and many shorter works for solo piano. His two most powerful and inventive creations–the Sonata, Op. 21 and the Variations and Fugue, Op. 23 for piano–require a powerful technique and Paderewski predicted that they would never be too popular.

With flowing melodies in abundance, most of Paderewski’s music reflects the singing quality of his playing. He also made use of Polish dance rhythms in many of his compositions. Two of the most popular piano miniatures that he often included in his own programs were the Cracovienne fantastique from Op. 14 and Melodie from Chants du Voyageur, Op. 8. Who has not heard Paderewski’s famous Minuet? For many decades, every doting parent anxiously awaited the day when their child could, at last, perform this Minuet in a local recital. This was the goal of every child taking piano lessons and considered a mark of achievement. In reality, this youthful piece written in a Mozart style isn’t especially difficult to play, but very effective as a virtuoso display.

The consummate patriot…

Paderewski’s friendships with many of the leading statesmen of Europe and America paved the way for his future political career. Beginning in 1910 he emerged as one of the best informed and best connected figures to represent Poland, a country that was at that time partitioned among her German, Austrian and Russian neighbors. The pinnacle of his political career came at the end of World War I, when the Big Four (Wilson, Clemenceau, Lloyd George and Orlando, unanimously said of Paderewski, who was Poland’s Prime Minister, “No country could wish for a better advocate.”

During World War I the U.S. Congress passed a resolution of sympathy and President Wilson, by proclamation, set January 1, 1916 as a day for giving to the suffering of the Polish people. Polish American organizations united to choose him as their leader, conferring upon him the power of attorney to act for them and decide all political matters in their name. This unique document bore the seals and signatures of all the Polish societies in the U.S. Through his leadership an army of volunteers of Polish descent was organized in North America to join in the fight for Poland’s freedom during World War I. Every day during roll call, Paderewski’s name was called and the entire army answered, “Present.”

Paderewski also authored a memorandum on Poland (which took over 36 hours of uninterrupted work) and delivered it to Colonel House on January 12, 1917, who in turn gave it to President Wilson. On January 23rd the president spoke of a “New Poland” saying, “I take it for granted…that statesmen everywhere are agreed that there should be a united, independent, autonomous Poland.” This became Point Thirteen of Wilson’s proclamation, which led to a new and independent Poland after World War I.

The Versailles Peace Treaty was signed in 1919 with Paderewski as Poland’s Prime Minister. His hands helped shape the new Poland and he became the new Poland’s first delegate at the Council of Ambassadors and the first Polish delegate to the League of Nations. At Geneva he was looked upon by everybody as a great patriot and distinguished statesman.

Paderewski’s speeches were considered among the finest oratorical achievements of the League, with every speech a masterpiece of clear thinking and brilliant delivery. When Paderewski left Paris, his colleagues thought of him as a great statesman, an incomparable orator, a linguist and one who had the history of Europe better in hand than any of his more illustrious associates. Had he been representing a power of the first class he easily would have become one of the foremost of those whose decisions were finally to be written into the peace. As it was, he played a great part nobly, and gave the world an example of patriotism and courage. When he addressed the League of Nations in Geneva in 1920, he received a standing ovation before and after his speech. He spoke for more than an hour without notes in French and then repeated it in English. He was the only speaker who did not use an interpreter.

The American Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, who distrusted Paderewski at first, later wrote about him in his book, The Big Four, that “His views were essentially sane and logical. What Mr. Paderewski has done for Poland will cause eternal gratitude. His career is one which deserves to be remembered not only by his countrymen, but by every man whom love of country and loyalty to a great cause stand forth as the noblest attributes of human character.”

Before World War I Paderewski spoke at the centenary of Chopin’s birth in 1910 in the city of Lwów, where a monument to the great Polish composer was unveiled. He finished his speech to a crowd of thousands of people at a time and place when they were under Russian rule with the following:

Let us brace our hearts to fresh endurance,

Let us adjust our minds to action, energetic, righteous;

Let us uplift our consciousness by faith invincible

for the nation cannot perish that has a soul so great, so immortal!

On the tenth anniversary of Polish independence in 1928 Paderewski received messages from four U.S. presidents, Coolidge, Taft, Hoover and Roosevelt acknowledging his work as a statesman. He was respected by leaders throughout the world. When he arrived in Brussels on one of his concert tours, the King and Queen personally went to the station to greet him; an action unheard of on the part of Royalty.

The model humanitarian…

Paderewski had to resume his piano career in 1923 for financial reasons, for even though he had earned more money than any artist ever did he spent most of it for his country and for mankind. As early as 1895 he created the Paderewski Fund in New York to establish triennial prizes to American composers, regardless of race or religion. Some of those winners were David Diamond, Gardner Reed and Wallingford Rieger. He established a similar fund for Composition in Leipzig in 1898. In London he gave to the Transvaal War Fund for the wounded, widows and orphans. To express gratitude to Herbert Hoover and other Americans for helping with the Polish Relief Fund, he turned over the proceeds of a concert series to purchase food for unemployed Americans in the 1920s. In 1932 he faced an audience of 16,000 in Madison Square Garden, the largest crowd in the history of music at that time, making $50,000 for the benefit of unemployed American musicians. He even paid for his own tickets to the event.

Throughout the years he made substantial contributions for various causes: for unemployed musicians in England, funds for playwrights, for Polish composers in Poland, for the construction of a concert hall in Switzerland, for rebuilding a Cathedral in Lausanne, for unemployed workers, for wartime orphans in Italy, for the building of dormitories for music students in France, for the Allied Soldier’s Hospital, for Jewish refugees from Germany in Paris in 1933, etc.. His was the largest individual contribution ($28,600) to the American Legion for disabled veterans. In 1924 during a benefit concert for Belgian charities the King and Queen rose together with the audience upon his arrival on the stage, a disarming violation of protocol. In Poland he commissioned the sculptor Gutzon Borglum to make a statue of Woodrow Wilson to be unveiled in Poznań to symbolize Poland’s gratitude for their newly acquired freedom.

Tireless artist and activist…

His presence and mastery has been recorded for posterity in 1936 when he appeared in the British motion picture, Moonlight Sonata. He was so well liked by all who came in contact with him that he was deluged with flowers from the “extras” working on the film as an expression of homage and gratitude. He was 76 years old at the time.

Three years later, when Paderewski was 79, Poland was invaded and World War II began. The Poles and their allies looked again to him to lead them. Although in ill health, he agreed without hesitation to travel to Paris to inaugurate a new government, but declined to be named Prime Minister again. His home in Switzerland was a place of refuge for emigres of many nationalities during WWII. No one was turned away without having been fed. His personal library was at the disposal of the members of the Polish Army who had been interned in Switzerland during WWII. Paderewski left his home in Switzerland in September of 1940 to travel to the U.S. and continue his efforts to help the Polish cause.

It was after one of the rallies in New Jersey on June 22, 1941 in extremely hot weather that he became ill and passed away a week later. His funeral mass in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York in 1941 was attended by close to five thousand mourners inside with another thirty-five thousand gathered outside. Statesmen and leaders of the political and musical world came to bid Paderewski goodbye. By presidential decree (an action taken only once before in U.S. history) he was buried at Arlington Cemetery in Washington, D.C. He was laid to rest under the mast of the battleship Maine until his body could be transported to a free Poland for burial. After Poland shed the Communist government, Paderewski’s remains were taken for a state burial in Warsaw in July of 1992.

Paderewski, a Californian…

Paderewski’s presence in California has been immortalized in two places. At the turn of the century he commissioned Polish artist, Jan Styka, to paint The Crucifixion, a gigantic canvas (93 feet by 178 feet wide) which is now on display in the massive Hall of the Crucifixion at the Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale. Life-size portraits of Paderewski and of Styka are also on display.

The other locality associated with Paderewski is a Central Coast town of Paso Robles, where he came in 1913 to visit the hot mud and sulfur water baths to relieve his rheumatism. Within a short time, in several consecutive purchases, Paderewski acquired over three thousand acres and transformed them to Rancho San Ignacio, a thriving plantation of walnut, almond and plum trees. In 1922 he planted 200 acres of Zinfandel and Petit Syrah grapes. Wines produced from these grapes won several awards, beginning with a gold medal at the 1933 California State Fair. A memorable article in the LA Times stated: “Some of his Zinfandel was as coveted as his music.” Since the early 1990s, there has been an annual Paderewski Festival in Paso Robles, featuring concerts by world famous artists, lectures, wine tastings, winery tours and historical exhibits. It is held at the beginning of November, commemorating Paderewski’s birthday. A Paderewski statue was dedicated in Paso Robles in November of 2012 and since 2016 a July 4 Paso Pops concert held in the open has been organized by the Paderewski Festival Board.

Although Paderewski traveled all over the world and was a long-term resident in Switzerland, he wrote in his Memoirs, “America, the country of my heart, my second home.” His heart is interned at the church of the Black Madonna in Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

Selected Compositions

Valse mignonne for piano, ca 1876 (dedicated to Gustaw Roguski)

Suite in E-flat major, for piano, ca 1879

Impromptu for piano, ca 1879. Published in Echo Muzyczne i Teatralne, 1879, No. 11, Warsaw

Dwa Kanony [Two Canons] for piano. Echo Muzyczne i Teatralne, 1882, No. 19, Warsaw

Krakowiak for piano (1884). Echo Muzyczne i Teatralne, 1887, No. 117, Warsaw (see also Op. 14, No. 6)

Powódź [The Flood]. Leaflet Na powodzian issued in Warsaw for the benefit of the Polish flood victims (1884)

2 Intermezzi: in G-minor and C-major, for piano, ca 1885. Echo Muzyczne i Teatralne, 1885, No. 77 (I), and No. 89 (II), Warsaw.

Canzone, chant sans paroles for piano, ca 1904. Bote & Bock, Berlin (ca 1904)

Hej, Orle bialy [Hey, White Eagle], Hymn for male chorus and piano. Words by composer (1917). K. T. Barwicki, Poznań 1926

List of OPUS NUMBERS

- Op. 1 Zwei Klavierstücke:1. Prelude e capriccio; 2. Minuetto in G-minor. Bote & Bock, Berlin (ca 1886)

- Op. 2 Trois Morceaux for piano: Gavotte in E-minor, Melodie in C-major, Valse Melancolique in A-major (dedicated to Theresa Wlasoff). Kruzinski & Lewi, Warsaw 1881

- Op. 4 Elegie for piano. Bote & Bock, Berlin 1883

- Op. 5 Danses polonaises for piano: Krakowiak in E-major, Mazurek in E-minor, Krakowiak in B-flat major (dedicated to Natalia Janotha). Bote & Bock, Berlin 1884; version for 4 hands (with Op. 9 ) ca 1892

- Op. 6 Introduction et Toccata for piano. Bote & Bock, Berlin 1884

- Op. 7 Vier Lieder for voice and piano. Texts by Adam Asnyk. 1. Gdy ostatnia róża zwiędła [The Day of Roses]; 2. Siwy koniu [To My Faithful Steed]; 3. Szumi w gaju brzezina [The Birch Tree and the Maiden]; 4. Chłopca mego mi zabrali [My Love is Sent Away]. Bote & Bock, Berlin ca 1886

- Op. 8 Chants du voyageur for piano dedicated to Helena Górska: 1. Allegro agitato; 2. Andantino; 3. Andantino grazioso [Melody in B-major]; also for violin and cello with piano and for orchestra, 4. Andantino mistico; 5. Allegro giocoso. Bote & Bock, Berlin 1883

- Op. 9 Danses polonaises for piano. Book I: 1. Krakowiak in F-major; 2. Mazurek in A-minor and 3. A-major; Book II: 4. Mazurek in B-flat major; 5. Krakowiak in A-major; 6. Polonaise in B-major. Bote & Bock, Berlin 1884-1885; version for 4 hands (with Op. 5 ) ca 1892

- Op. 10 Album de mai. Scènes romantiques for piano dedicated to Anette Essipoff-Leschetizky: 1. Au soir; 2. Chant d’amour; 3. Scherzino; 4. Barcarolle; 5. Caprice (Valse). Bote & Bock, Berlin 1884

- Op. 11 Variations et fugue sur un thème original for piano (1883). Bote & Bock, Berlin ca 1885

- Op. 12 Tatra Album: Tanze und Lieder des polnischen Volkes aus Zakopane dedicated to Tytus Chałubiński, Books I & II (1883). Ries & Erler, Berlin 1883-1884; version for 4 hands 1884

- Op. 13 Sonate pour violon et piano in A minor dedicated to Pablo Sarasate (1882). Bote & Bock, Berlin 1885.

- Op. 14 Humoresques de concert for piano. Book I (à l’antique): 1. Ménuet célèbre; 2. Sarabande; 3. Caprice (genre Scarlatti); Book II (à la moderne): 4. Burlesque; 5. Intermezzo polacco; 6. Cracovienne fantastique (1887). Bote & Bock, Berlin 1887-1888

- Op. 15 Dans le desert–tableau musical en forme d’une toccata for piano dedicated to Anette Essipoff-Leschetizky (1888). Bote & Bock, Berlin ca 1888

- Op. 16 Miscellanea for piano: 1. Légende No. 1 in A-flat major; 2. Mélodie in G-flat major; 3. Theme varié in A-major; 4. Nocturne in B-flat major; 5. Légende no. 2 in A-major; 6. Un moment musical; 7. Menuet in A-major (1888). Bote & Bock, Berlin ca 1888-1894. No. 6: Un moment musical also published in Echo Muzyczne i Teatralne 1892, no. 435, Warsaw

- Op. 17 Concerto in A minor for piano and orchestra dedicated to Theodor Leschetizky (1888). Bote & Bock, Berlin 1890

- Op. 18. 1893. Sześć pieśni [Six Songs] for voice and piano dedicated to Władysław Mickiewicz. Texts by Adam Mickiewicz: 1. Polały się łzy [Mine Eyes Have Known Tears]; 2. Piosnka dudarza [The Piper’s Song]; 3. Moja pieszczotka [My Sweet Maiden]; 4. Nad wodą wielką i czystą [By Mighty Waters]; 5. Tylem wytrwał [Pain Have I Endured]; 6. Gdybym się zmienił [Might I But Change Me] (1893). Bote & Bock, Berlin 1894

- Op. 19 Polish Fantasy on original themes for piano and orchestra dedicated to Princess R. Bassaraba de Brancovan (1893). Bote & Bock, Berlin 1893; G. Schirmer, New York

- Op. 20 Manru–Lyrisches Drama in drei Aufzugen (1892-1901). Libretto in German by Alfred Nossig, based on the novel, Chata za wsią [A Cottage Outside the Village] by Józef Ignacy Kraszewski. Bote & Bock, Berlin 1901; Piano score with English and German texts, G. Schirmer, New York. (World premiere: Dresden, 29 May 1901)

- Op. 21 Sonata in E-flat minor for piano (1903). Bote & Bock, Berlin 1903

- Op. 22 Douze mélodies sur de poésies de Catulle Mendès (1903). 1. Dans la forêt; 2. Ton cœur est d’or pur; 3. Le ciel est très bas, 4. Naguère; 5. Un jeune pâtre; 6. Elle marche d’un pas distrait; 7. La nonne; 8. Viduité; 9. Lune froide; 10. Querelleuse; 11. L’Amour fatal; 12. L’Ennemie. Heugel, Paris 1903

- Op. 23 Variations et fugue sur un thème original in E-flat minor for piano (1903). Bote & Bock, Berlin 1903

- Op. 24. 1903-9. Symphony in B-minor, Polonia (1903-1909). Heugel, Paris 1911. (World premiere: 12 February 1909)

Links

Compositions (PMJ 4/2)

Writings (PMJ 4/2)

Paderewski’s Bibliography

Articles: Polish Music Journal 4/1 (2001)

The Unknown Paderewski: Polish Music Journal 4/2 (2001)

Paderewski Festival (Paso Robles)

Site at the Polish American Center

Page updated on 20 April 2018