One cannot predict anything, but I would nonetheless like my music to survive, just like Szymanowski’s. Times have changed, yet Chopin’s music remains. Thus, I hope, my music will also remain.”

[Penderecki for National Chopin Institute, quoted at onet.pl]

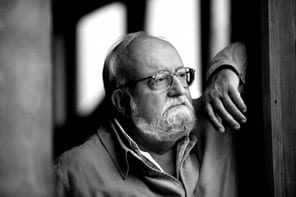

Krzysztof Penderecki died in Kraków in the early hours of Sunday morning, March 29, following a long illness. Widely acclaimed as one of the main figures in Polish contemporary music, Penderecki was a world-renowned composer, conductor, as well as professor and Rector of the Kraków Music Academy. He was 86 years old.

Born in Dębica on 23 November 1933, Penderecki began to study music by taking piano and violin lessons. He also began composing at an early age and eventually studied with Artur Malawski and Stanisław Wiechowicz at the State Higher School of Music (now Music Academy) in Kraków. His first steps as a composer—Strofy, Emanacje and Psalmy Davida—were recognized with three first prizes at the Polish Composers’ Union [ZKP] competition for composers in 1959.

Born in Dębica on 23 November 1933, Penderecki began to study music by taking piano and violin lessons. He also began composing at an early age and eventually studied with Artur Malawski and Stanisław Wiechowicz at the State Higher School of Music (now Music Academy) in Kraków. His first steps as a composer—Strofy, Emanacje and Psalmy Davida—were recognized with three first prizes at the Polish Composers’ Union [ZKP] competition for composers in 1959.

A prolific and determined worker, Penderecki authored four operas, eight symphonies, oratorios, orchestral and vocal works, as well as chamber and solo instrumental music. Among the most recognized of his early compositions are Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima (1960), Polymorphia for 48 Strings (1961), Fluorescences (1962), St. Luke’s Passion (1965), Dies irae (1967), and the opera Devils of Loudun (1969).

Lacrimosa (1981), one of Penderecki’s first deeply introspective compositions, is a short work commemorating the 1970 strikes of the Polish dockworkers; this poignant, one-movement epitaph to the victims of the socialist state was later joined with several others movements written sequentially throughout the 1990s and eventually incorporated into the Polish Requiem (2005).

Moving onto the world stage as a noted composer, Penderecki’s Cello Concerto—written in 1982 for Mstislav Rostropovich—belongs to a series of works for solo instruments and orchestra that began with a 1977 Violin Concerto written for another great virtuoso, Isaac Stern. Commissioned to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution, Penderecki’s Fourth Symphony (1989) and chamber-sized Sinfonietta per archi (1992) explore various aspects of writing for large and small ensembles. Violin Concerto No. 2 “Metamorfozy” (1992), written for Anne-Sophie Mutter, earned Penderecki one of his five Grammy Awards in 1998. Pieśni zadumy i nostalgii [Songs of contemplation and longing], a quiet work written to texts by Polish poets dating from 2010, represents still another, more meditative aspect present in many of Penderecki’s late compositions.

Abandoning atonality and various avant-garde techniques, by the early 1980s Penderecki gravitated towards tonal harmonies and rich orchestral textures typical of late nineteenth century German music. This rather surprising stylistic turning point came in 1980, perhaps encouraged by Zubin Mehta and the New York Philharmonic commission. “I sat down and demonstrated that one could write—as some people would say—a romantic symphony. I did so also for the public and it was very successful. That’s how a new phase in my music began,” said Penderecki in one of his interviews for a Polish daily, Rzeczpospolita. Penderecki’s “Christmas Symphony” (also known as his Symphony No. 2), quotes the easily recognizable Silent Night and belongs to a large group of more ostensibly accessible works embracing a wide spectrum of religious texts and themes. Such topics were explored in extenso in such works as Utrenia I & II –The Entombment of Christ and The Resurrection (1970-1971), Magnificat (1974), Te Deum (1980), Veni Creator (1987) as well as in hymns to St. David and St. Adalbert, written in the late 1990s.

Undoubtedly, Penderecki’s long and productive life reflected a great variety of sources and musical inspirations. Although his artistic trajectory began with sonorist avant-garde works in the 1960s, when Penderecki established himself as one of the leading lights of Polish contemporary music alongside Wojciech Kilar (1932-2013) and Henryk Mikołaj Górecki (1933-2010), he also wrote music inspired by Bach’s oratorios and Russian orthodox choral traditions. Later on, Penderecki incorporated sounds from the Far East into his Symphony No. 5, “Korean” (1992) and Symphony No. 6 “Chinese” (2017). Returning to texts by a group of early 20th century German poets—who proved a lifelong fascination for the composer—led to his twelve-movement Symphony No. 8, subtitled “Lieder der Vergänglichkeit” [Songs of Transience], completed in 2008.

A substantial number of Penderecki’s works were composed in an old country manor house in Lusławice that he lovingly restored to its noble and bygone splendor, and planted a botanical garden around it. A keen amateur horticulturist, he brought in trees, shrubbery and various other specimens from all over the world, carefully adding them to a uniquely laid out grounds that also featured two elaborate mazes. Right across from Penderecki’s Lusławice property, the new Krzysztof Penderecki European Music Center with excellent concert halls, recording studios and other facilities, was opened in 2013. It has since become an important concert venue in southeastern Poland.

Penderecki’s highly original music was used to great effect in numerous film soundtracks, including Wojciech Has’s The Saragossa Manuscript (1965), Billy Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), Jerzy Skolimowski’s Ręce do góry (1981), Peter Weir’s Fearless (1993), Andrzej Wajda’s Katyń (2007) and Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island (2010). David Lynch, a devoted fan of Penderecki’s avant-garde opus, used it in Wild at Heart (1990), Inland Empire (2006), and Twin Peaks (2017). Another example of Penderecki’s music eliciting a worldwide response—sometimes in unexpected corners—include Jonny Greenwood (of Radiohead fame) who wrote 48 Responses to Polymorphia and used elements of Threnody for Victims of Hiroshima in his compositions.

Active as teacher and mentor to a number of important musicians worldwide, Krzysztof Penderecki served as Rector of Kraków Music Academy (1972-1987) and taught at Yale University (1973-1978). Beginning in the mid-1970s, he was also internationally active as a conductor. His frequent appearances on stages leading a variety of orchestras at concerts and festivals in Poland included the annual Eastertide Beethoven Festival in Warsaw that, for a number of years, was organized by Elżbieta Penderecka—his wife since 1965.

[Sources: rp.pl, rp.pl, onet.pl, onet.pl, wiadomosci.wp.pl, theguardian.com]