5 February 1909, Łódź – 17 January 1969, Warsaw

Biography

Grażyna Bacewicz is an interesting case in the history of Polish music. Like Fryderyk Chopin, she came from a bi-national family and, with a Lithuanian father and a Polish mother, she could choose her national identity. She chose to be Polish, but her brother Witold moved back to Vilnius with her father, and ended up in the U.S. as a leading, though little understood, Lithuanian emigré composer. Polish musicologists, Krzysztof Droba, Małgorzata Gąsiorowska, and Marta Szoka, are now at the forefront of a dialogue with their Lithuanian colleagues, organizing joint sessions and publishing books to celebrate the multifarious talents of the Bacewicz family.

Bacewicz had received hear earliest musical training from her father; she started learning violin, piano and theory when she was five years old. Her other older brother, Kiejstut, became a pianist and frequently accompanied her in performances. The youngest sister, Wanda, is a poet who serves as family historian and the guardian of Grażyna’s memory. A child prodigy, Grażyna gave her first concert at age of seven (with her brothers); she composed her first piece, Preludes for Piano, at the age of thirteen. After enrolling at the Warsaw Conservatory of Music to study violin and piano, in 1928 Bacewicz began studies of philosophy at the University of Warsaw (she completed a year and a half). She continued her music training at the Conservatory, studying composition with Kazimierz Sikorski, violin with Józef Jarzębski and piano with Jan Turczyński; she graduated summa cum laude in 1932.

Karol Szymanowski, who was a professor of the Warsaw Conservatory, advised all young composition students to go to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger and Bacewicz joined this group of Poles in the 1930s. She studied composition with Boulanger, and violin with André Touret and Carl Flesch. At that time she adopted the neoclassical style for her compositional language and became the first Polish woman composer to achieve national and international stature. After the completion of her studies she proceeded to participate in countless concerts and festivals as performer, composer and jury member. In the 1930s she was the principal violinist for the Polish Radio Orchestra, organized by the famous conductor, Grzegorz Fitelberg; her repertoire included solo parts in the Szymanowski Violin Concerti. This orchestra gave her a chance of hearing her own music, including Violin Concerto no.1 and Three Songs for tenor and orchestra. During the war, she lived in Warsaw, continuing to compose and giving underground concerts (e.g. premiering her Suite for Two Violins). She also dedicated some time to family life: married in 1936, she gave birth to her only daughter, Alina Biernacka (now a famous painter), in 1942.

After the war, she returned to work as a professor in the State Conservatory of Music in Łódź. During the Stalinist period from 1945 to 1955, Bacewicz, like all other composers, was subject to an increasing ideological control of the new, socialist government. Initially, she still continued to travel and perform abroad: she visited Paris for the fifth time, giving a concert at the Ecole Normale de Musique. It is around that time that she decided to end her involvement with music as a performer and switch to composing as a sole occupation. Before she was able to do so, she made a number of recordings, often with her pianist brother, Kiejstut. They recorded, for instance, Bacewicz’s Fourth Sonata for Violin and Piano: this recording, issued by Polskie Nagrania – Muza, XW-72, bears no date, but is located by Wanda Bacewicz, the musician’s poet-sister, in mid 1950s. The finale is a display of virtuosity, and the composer finds a true counterpart in her performing “alter ego,” but it is the slow movement (Andante ma non troppo) with is dark arpeggios set in the low register of the piano and the poignant melodic line of the violin, that is mysterious and fascinating, especially in the masterly rendition by the composer-virtuosa.

It is important to note that Grażyna Bacewicz was also an excellent pianist. She premiered and often performed her Sonata No. 2 for piano (1953). This Sonata is available in a recording by Nancy Fierro, a dedicated promoter of music by women composers, on her Riches and Rags CD, available from the International Alliance for Women in Music. Another, wonderful recording by Krystian Zimerman has been issued by Olympia (OCD 392). The fact that this Sonata was composed at the height of Stalinist repressions in Poland, is yet another proof that political circumstances do not necessarily bear a negative influence on the quality of the music. The final movement of the sonata juxtaposes a neo-Baroque toccata, with its lively moto perpetuo rhythms, with a Polish folk-dance, a vivacious oberek.

Bacewicz’s compositional career became her primary preoccupation after 1954, when she suffered serious injuries in a car accident. She was led in this direction by a string of compositional awards and commissions, recognizing the value of her music (about which she was highly critical herself). When she was 39 years old, Bacewicz received an honorable mention at the International Olympic Games Art Contest in London for her Olympic Games Cantata. She was also awarded the second prize at the prestigious Chopin Contest for Composers, two more prizes at the Second Contest, the music award of the City of Warsaw for her work as a composer, virtuoso, organizer and teacher. In 1950, her Concerto for String Orchestra received the National Prize and was performed by the National Symphony Orchestra in the United States. This work, written in the tradition of Baroque serenades and suites contains borrowings from the Baroque concerto grosso, elements of concertante style, and Baroque-style repeated figurations. The melody of the opening Allegro displays an interesting, oscillating contour – it is “tied” to a fixed point to which it constantly returns. The themes are derived from one another; the second theme of this “sonata-allegro form” is not gentle and singing in quality (as expected in this form), but rhythmic, with a strong dynamic momentum. The slow Andante sets an expressive melody against a sublime, shimmering background. The Concerto ends with an exuberant finale featuring cross-rhythms, interplay of brief motives, sudden harmonic turns, and incisive rhythmic profiles. This work remains a favourite with Polish chamber orchestras and it would be great to hear it performed more often outside of Poland.

Her series of awards continued: she won the first prize for her String Quartet No.4 at the 1951 International Contest for Composers, Liège. In 1955, she received awards at the Polish Composer’s Union Contest, and prizes from the Minister of Culture and Art for her Symphony No.4, Violin Concerto No.3 and String Quartet No.3. At the end of 1958, she completed her final, and, perhaps, the greatest neoclassical composition, Music for Strings, Trumpets and Percussion, which was performed at the Warsaw Autumn in 1959. This piece received the first prize in the orchestral division and third prize overall at UNESCO’s International Rostrum of Composers in 1960. Since 1956, when the political thaw allowed changes in musical life and a greater interaction with the West, the compositional scene in Poland was transformed by the arrival of the newest avant-garde techniques and fashions. The first Warsaw Autumn International Festival of Contemporary Music was held in 1956 and three works by Bacewicz were performed: String Quartet No.4, Concerto for String Orchestra, and the Overture.

These works may be still dubbed neoclassical, but, similarly to Witold Lutosławski, Bacewicz soon reacted to the general mood of stylistic changes by revising her aesthetics and technique. She worked out her own brand of sonorism in a series of works from the 1960s, including Pensieri Notturni (1961), Violin Concerto No. 7 (1965), and her final piece, the ballet Desire (1967-69) based on a play by Picasso. Bacewicz’s new, aphoristic, fragmentary style includes the use of a kaleidoscopic variety of sound images and timbres. Yet the music is never overbearing, never too aggressive, too dissonant. She retained the neoclassical values of clarity and esprit. Bacewicz’s concern for perceptual clarity had a bearing on her orchestration: she was convinced that in music “one needs a lot of air” and she preferred to contrast orchestral tutti with soli or small groups of instruments instead of suffocating the listeners with “a big mass of sounds for a long span of time.” It is sufficient to compare her Seventh Violin Concerto with such typical sonoristic works as Górecki’s Scontri or Penderecki’s Threnody. There is a huge expressive gap separating these composers from each other. However, the distance from the elegant sonorities of Witold Lutosławski (e.g. Paroles tissées of 1965 or Les espaces du sommeil of 1975) is not as pronounced. Unfortunately, this period of Bacewicz’s creative work is not yet well appreciated by musicologists. Performers seem to know better. The Violin Concerto No. 7, for instance, was awarded a prize of the Belgian Government and Gold Medal at the Queen Elizabeth of Belgium International Competition for Composers in Brussels. According to violinist Andrzej Grabiec, this work now belongs among the masterpieces of the violin repertoire. Its recording is available from Olympia, OCD 392 (by Piotr Jankowski, violin, with the National Philharmonic Orchestra, Andrzej Markowski, cond.). It would be interesting to re-examine this composition from the standpoint of its role in 20th-century Polish music.

Bacewicz is generally known as composer of instrumental music that is usually labelled neoclassical, but with a discernible stylistic evolution from (1) early influence of Szymanowski and assimilation of French neoclassicism (Boulanger), (2) to her own mature neoclassical style created in her second period, 1944-1958, and to (3) a period of stylistic experimentation with sonorism, 12-tone techniques, aleatoricism, and collage. She was one of the founders of the Warsaw Autumn Festival; became the first woman vice-president of the Union of Polish Composers (since 1960) and a professor of composition at the Warsaw PWSM (since 1966). She served as Jury member at the Marguerite Long-Jacques Thibaud International Competition in 1953, Tchaikovsky International Competition in 1958, and International Competition in Naples in 1967, International Quartet Competition in Budapest in 1968, as well as the Chair of the jury at Wieniawski International Violin Competitions in 1957 and in 1967. In Poland, there are schools and streets bearing her name, while sculptures portraying her adorn urban parks. You might find more information about her in the excellent brief biography by Judith Rosen. According to another woman composer, Bernadetta Matuszczak, Bacewicz was the first woman accepted as an equal by her male peers:

“In Poland, Grażyna opened the way for women composers. . . It was difficult for her, but with her great talent she won, she became famous. . . . Afterwards, we had an open path, and nobody was surprised: ‘My God, a woman composer again!’ Bacewicz had already been there, so the next one also had a right to exist.”

Female students of composition found hope for themselves when seeing Bacewicz’s name on the programs of the Warsaw Autumn Festivals and reading monographs about her. Of course, these works were published and available: in 1969, the year of her death, the catalogue of PWM, included 36 of Bacewicz’s compositions, the most by any composer! Incidentally, the respect for Bacewicz’s music has not diminished after her death in 1969. In various interviews, Paweł Szymański (composer), Krzysztof Baculewski (composer and musicologist) and Olgierd Pisarenko (music critic, associate editor of Ruch Muzyczny) have all highly praised Bacewicz’s music and emphasized her importance in the history of Polish music. Unlike some of the most avant-garde oriented composers and musicologists, all the musicians, especially string players, that have performed her works become great champions of her music.

Bacewicz In Her Own Words

“I do not agree with a statement that I hear quite often that if a composer discovered his own musical language he should adhere to this language and write in his own style. Such an approach to this matter is completely foreign to me, it is identical with the resignation from progress, from development. Each work completed today becomes the past yesterday. A progressive composer would not agree to repeat even himself. He has to not only deepen and perfect his achievements, but also broaden them. It seems to me, that for instance in my music, though I do not consider myself an innovator, one can notice a continuous line of development. […] My compositional workshop and the emergence of the work is for me something personal and intimate. Contemporary composers, and at least a considerable number of them, have a different stance. They explain what system they used, in what way they arrived at something. I do not do that. I think that the matter of the way by which one arrived at something is, for the listeners, unimportant. What matters is the final result, that is the work itself.”

[A 1964 interview for Polish Radio, published in Ruch Muzyczny 33 No.3 (1989)]

“I divide my music into three periods – (1) youth – very experimental, (2) – inappropriately called here neo-classical and being really atonal, and (3) the period in which I’m still located. I arrived at this period by way of evolution (not revolution), through the Music for Strings, Trumpets and Percussion, the 6th String Quartet (partly serialized), the 2nd Sonata for Violin Solo, and the Concerto for large symphony orchestra.”

[“A Draft Answer to an Unknown Questionnaire,” Ruch Muzyczny No. 7 (1969)]

An Impression from India:

“During one of the concerts, Statkiewicz, who was enjoying a great popularity in India, played Szymanowski’s La fontaine d’Arethuse. At a moment, when a trill and an arpeggio followed a cantilena in the violin part, the hall was filled with a quiet breeze of “clicking” [the sound made when giving a kiss]. Naturally, Statkiewicz continued to perform. The sounds in the audience returned, but this time with a certain shade of impatience, or even insistence. Statkiewicz, not guilty of anything, played on. The hall was filled with a quiet murmur. We did not understand what it was about.”

[Polish Music Journal 1 No. 2 (1998)]

“After the concert we went to our room – all of us from Poland and many Indians – and a strange conversation followed. One of the Indians, through a translator, asked Statkiewicz why he did not respond to the wish of the audience. He politely answered that he did not know what this wish was. Now, the Indian was surprised and said: “But we communicated to you our wish to repeat this beautiful sound that you made.” – “How come?” – Said Statkiewicz – “Was I expected to interrupt the piece and repeat a fragment again just because the audience liked it?” – “Yes, of course, of course,” The Indian answered. For him and for all other Indians in that hall this was the most obvious thing in the world.”

[Znak szczególny, Warsaw: Czytelnik, 1974, 40]

From Her Letters:

“The majority of Polish composers have freed themselves from Szymanowski’s influence. In my compositions, I mostly pay attention to the form. If you are building something, you will not pile stones randomly on each other. It’s the same as a musical work. The principles of construction don’t have to be old fashioned. The music can be simple or complicated. It depends on the composer, but it has to be well constructed. I don’t have to even mention good orchestration. I threw away my old compositions. I see many things in them that I don’t like, so why should I keep them?”

[Letter to brother Witold (Vytautas Bacevicius), 1 March 1947]

“I walk quite alone, because I mainly care about the form in my compositions. It is because I believe that if you place things randomly or throw rocks on a pile, that pile will always collapse. So in music there must be rules of construction that will allow the work to stand on its feet. Naturally, the laws need not be old – God forbid. The music may be simpler or more constructed – it’s unimportant, it depends on the language of a particular composer – but it must be well constructed.”

[Letter to Vytautas Bacevicius, 21 March 1947]

“For me the work of composing is like sculpting a stone, not like transmitting the sounds of imagination or inspiration. The majority of contemporary composers work as systematically as bureaucrats. If there is no inspiration one does the menial “workshop” jobs, if there is inspiration the creative work continues. Discipline, strict discipline in composition is essential to for me. There is a saying: the house will fall down if it were to be built without principles. However, since dodecaphony does not appeal to me very much I am sitting alone and working out my own system.”

[Letter to Vytautas Bacevicius, 23 October 1958]

SELECTED COMPOSITIONS

For List of Works, click here.

For Bibliography, click here.

Chamber Music

Quintet for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon and horn — 1932 (PWM 1933)

Theme with Variations for piano and violin — 1934 (PWM 1934)

Trio for oboe, violin and cello — 1935 (PWM 1995)

String Quartet No.1 — 1938 (PWM 1997)

String Quartet No. 2 — 1943 (PWM 1998)

Suite for 2 violins — 1943 (PWM 1950)

Easy Duets on Folk Themes for 2 violins — 1945 (PWM 1950)

Concertino for violin and piano — 1945 (PWM 1950)

Sonata da Camera for violin and piano — 1945 (PWM 1950)

Easy Pieces for violin and piano — 1946 (PWM 1946)

Capriccio for violin and piano — 1946 (PWM 1946)

String Quartet No.3 — 1947 (PWM 1948)

Sonata No.1 for violin and piano — 1946 (PWM 2000)

Polish Dance for violin and Piano — 1948

Quartet for 4 violins — 1949 (Warszawa 1949,PWM 1971)

Sonata No.3 for violin and piano — 1948 (PWM 1950)

Sonata No.4 for violin and piano — 1949 (PWM 1952)

Sonata No.5 for violin and piano — 1951 (PWM 1954)

Oberek for violin and piano — 1949 (PWM 1950)

Oberek No.2 for violin and piano — 1951 (PWM )

Melody and Capriccio for violin and piano — 1949 (PWM 1950)

String Quartet No.4 — 1951 (Edgar Tyssens Liège, Belgium, 1952 (PWM 1987)

Mazovian Dance for piano and violin — 1951 (PWM 1952)

Piano Quintet No.1 — 1952 (PWM 1953)

Lullaby for piano and violin — 1952 (PWM 1952)

Slavonic Dance for piano and violin — 1952 (PWM 1953)

Humoresque for piano and violin — 1953 (PWM 1959)

Polish Capriccio for piano and clarinet — 1954

Partita for piano and violin — 1955 (PWM 1957)

String Quartet No. 5 — 1955 (PWM 1958)

Sonatina for oboe and piano — 1955 (PWM 1988)

Sonata No. 2 for violin and piano — 1958

String Quartet No .6 — 1960 (PWM 1961)

Quartet 4 for cellos — 1964 (PWM 1965)

Incrustations for horn and chamber ensemble — 1965 (PWM 1970)

Trio for oboe, harp and percussion — 1965 (PWN 1973) posthumous facsimile edition

Piano Quintet No. 2 — 1965 (PWM 1972)

String Quartet No. 7 — 1965 (PWM 1989)

Orchestral Music

Overture — 1943 (PWM 1955)

Concerto for string orchestra — 1948 (PWM 1951)

Symphony No. 2 — 1951

Symphony No. 3 — 1952 (PWM 1954)

Symphony No. 4 — 1953 (PWM 1955)

Partita — 1955 (PWM 1959)

Variations — 1957 (PWM 1960)

Music for Strings, Trumpets and Percussion — 1958 (PWM 1960)

Pensieri Notturni — 1961 (PWM 1961)

Concerto for large orchestra — 1962 (PWM 1962)

Musica sinfonica in tre movimenti — 1965 (PWM 1966)

Divertimento for string orchestra — 1965 (PWM 1967)

Contradizione for chamber orchestra — 1966 (Ricordi 1967) (PWM 1970)

In Una Parte — 1967 (PWM 1969)

Concerti with Orchestra

Concerto No. 1 for violin and orchestra — 1937 (PWM- CBN) rental

Concerto No. 2 for violin and orchestra — 1945 (PWM- CBN) rental

Concerto No. 3 for violin and orchestra — 1948 (PWN 1950)

Concerto for piano and orchestra — 1949 (PWN 2001)

Concerto No. 4 for violin and orchestra — 1951 (PWN 1953)

Concerto No. 1 for cello and orchestra — 1951 (PWN 1953)

Concerto No. 5 for violin and orchestra — 1954 (PWN 1956)

Concerto No. 2 for cello and orchestra — 1963 (PWN 1964)

Concerto No. 7 for violin and orchestra — 1965 (PWN 1979) co-published by Moeck Vertag

Concerto for 2 pianos and orchestra — 1966 (PWN 1969) co-published by Moeck Vertag

Concerto for viola and orchestra — 1968 (Edizioni Curci Milano 1969) (PWM co-editors; arrangement: 1969; orchestral score:1981)

Vocal-Instrumental Music

3 songs for tenor and orchestra — 1938 (PWM CBN – rental)

Olympic Cantata for mixed choir and orchestra — 1948 (PWM-CBN)

Acropolis cantata for mixed choir and orchestra — 1964 (PWM -CBN)

Stage Works

Peasant King — 1953 (PWM- CBN – rental)

The Adventure of King Arthur — 1959 (PWN-CBN)

Esik in Ostend — 1964 PWN- CBN)

Desire — 1968/69 (PWM facsimile edition 1985)

Songs (Voice and Piano)

Roses — 1934

Speak to me, My Dear — 1936

Here is the Night — 1947

Leave-taking — 1947

A Streak of Shadow — 1948

On the Big and Clear Water — 1955

Large Bell and Small Bells— 1955

I Have a Headache — 1955

Little Magpie — 1956

Three songs to 10th century Arabic texts: Mamidło [Illusion], Inna [Another], and Samotność [Loneliness] — 1938

Courtship for unaccompanied men’s choir — 1968 (PWM 1975)

Music for Solo Instruments

Children’s Suite for piano — 1933/34 (PWN 1966)

Krakowiak for piano — 1949 (PWN 2001)

2 Studies in Double Notes for piano — 1955 (PWM 1999)

Sonata No. 2 for piano — 1953 (PWM 1955)

Rondino for piano — 1953 (PWM 1993)

Sonatina for piano — 1955 (PWM 1977)

10 Concert Studies for piano — 1956 (PWM 1958)

Little Triptych for piano — 1965 (PWM 1966)

Sonata for violin — 1941 (PWM 1978)

Sonata No. 2 for violin — 1958 (PWM 1960)

Polish Capriccio for violin — 1949 (PWM 1950,1952)

Capriccio No. 2 for violin — 1952 (PWM 1952)

Four Capriccios for violin — 1968 (PWM 1969)

Esquisse for organ — 1966 (PWM 1973)

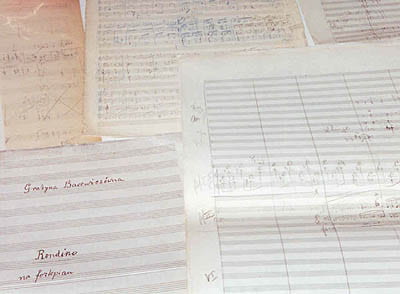

Manuscripts at USC

All manuscripts below were generously donated by Wanda Bacewicz in 1985 (parts for the Concerto and Contradizione) and in 2000 (the remainder of the collection), and are a part of the PMC’s Manuscript Collection.

• Convoi de joie (1933); piano reduction for two pianos; score in blue ink; French music paper, 2 pages

• Rondino for piano solo (1953); 5 pages in black ink with editorial notes in red pencil by PWM publishers; on Polish music paper

• Dzwon i dzwonki (1955); song for soprano and piano to Adam Mickewicz’s poem; 3 pages of sketches in pencil, without text

• Concerto per 2 pianoforti e orchestra (1966); piano reduction; 61 pp. A copy with handwritten annotations by the composer in pencil and ink

• Concerto per 2 pianoforte e orchestra (1966); orchestral parts made by the composer

• Concerto per 2 pianoforti e orchestra (1966); orchestral draft in pencil; 52 pages (from m. 8) on Polish music paper

• Contradizione for orchestra (1966); orchestral parts

• String Quartet (no date); 2 pages in blue and grey pencil, 49 mm

• String Quartet (no date); two other sets of sketches, assorted pages

• Sketches for an unidentified orchestral piece (1960s?)

• Page from the ballet Desire with the composer’s annotations (1969)

Links

Judith Rosen’s Article, Polish Music Journal

Bibliography

PMC Books on Bacewicz (PMHS Vos. 2 & 3)

Publisher’s Site: PWM

Page updated on 13 July 2018