By Cindy Bylander

[Article originally published in Musical Opinion Quarterly, April-June 2014. Used by permission of the author]

In May 2013, the Grand Theatre/National Opera in Warsaw presented the first installment of Projekt P [Project P], which brings together “the hottest young Polish creators” in order to develop genre-shattering new operas. In the case of the first installment, it was Wojtek Blecharz’s Transcryptum and Jagoda Szmytka’s Dla głosów i rąk [For Voices and Hands] that were premiered. American musicologist Cindy Bylander wrote an in-depth review of Transcryptum for Musical Opinion Quarterly, which is excerpted below.

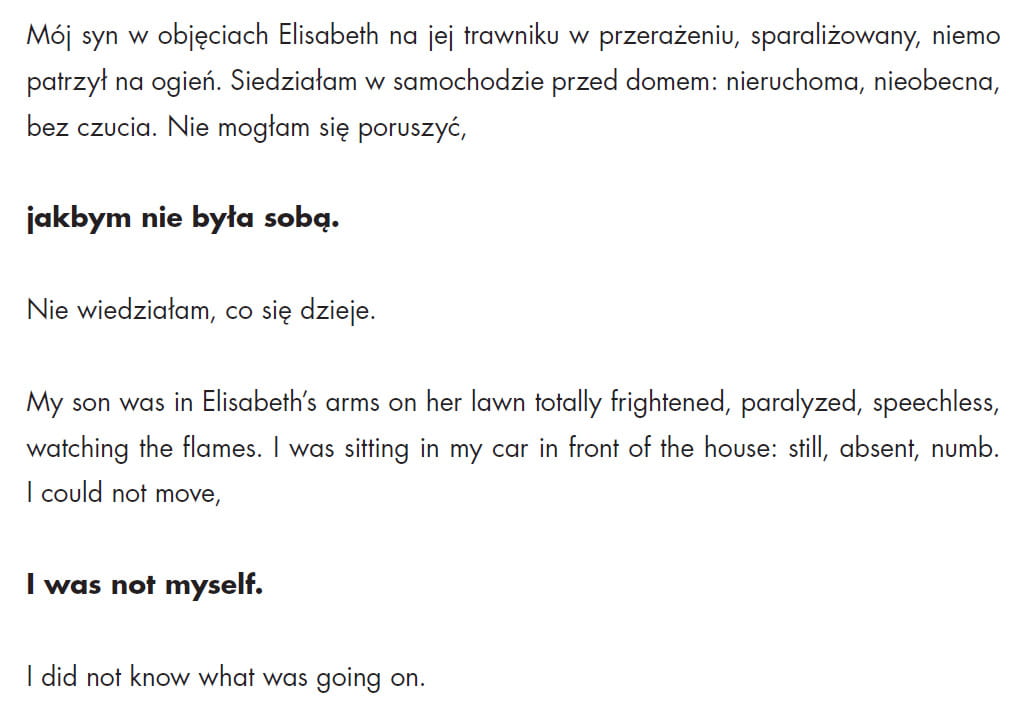

Blecharz’s contribution, in particular, was highly unusual for its rejection of nearly everything that is typically expected of an opera, even those that have emerged in the 21st century. His reinterpretation of the essential components of the genre—libretto, staging, drama, music—bore homage to its recent predecessors yet challenged the very definition of such works. His attempt to reinvigorate the genre by changing the relationship between audience and participant engaged all involved in unexpected ways. For example, what Blecharz calls the libretto existed only in printed form and consisted of snippets of text to be read by audience members at an appointed time during the production (Ex. 1). Instead of a dramatic narrative, fragmentary recollections of a horrific event were introduced, their meanings obscured by the transient nature of each segment. All participants wore drab gray or black clothing rather than distinctive costumes reflective of each character’s role. Written for seven instrumentalists, vocalist, dancer, and actor, the score contains few notated pitches. Sung texts, which Blecharz has lamented as the most artificial part of opera,1 are largely avoided, as are conventional means of instrumental performance. Traditional acting is also absent, although theatrical gestures are indicated at times in the instrumental parts. Video and sound projections either accompanied the live music or formed standalone offerings. The sole trained singer, mezzosoprano Anna Radziejewska, did not have a central role, even though Blecharz wrote the piece with her in mind. In another twist, Blecharz filled the roles of both composer and director, collaborating with experts in lighting, video and set design.

What ultimately distinguished Transcryptum from its peers and predecessors, however, was its staging. Blecharz has described the piece as both an opera and an “opera-installation.” It is site-specific, for he exploited the acoustical and visual possibilities of a variety of spaces within Warsaw’s opera building.

What ultimately distinguished Transcryptum from its peers and predecessors, however, was its staging. Blecharz has described the piece as both an opera and an “opera-installation.” It is site-specific, for he exploited the acoustical and visual possibilities of a variety of spaces within Warsaw’s opera building.

…

Transcryptum, for all of its innovative characteristics, also adopted certain attributes of its predecessors. Stockhausen’s expansion of operatic activity into public space was taken a step further by Blecharz’s nearly complete avoidance of traditional performing areas. As in Stockhausen’s Licht, the instrumentalists in Transcryptum are frequently the main attraction, appearing alone or as part of a duet or trio (they perform together only for the closing piece). Reminiscent of Lachenmann’s Das Mädchen mit den Schwefelhölzern, they are identified only by generic titles such as “mother.”2 Displaying a deeper indebtedness to Lachenmann as well as to Penderecki, Cage, and others, Blecharz’s music consists almost entirely of extended performing techniques and prepared instruments. Such writing is the norm for the composer’s output to date, for which the 32 year old has already garnered awards, commissions, and critical acclaim.3

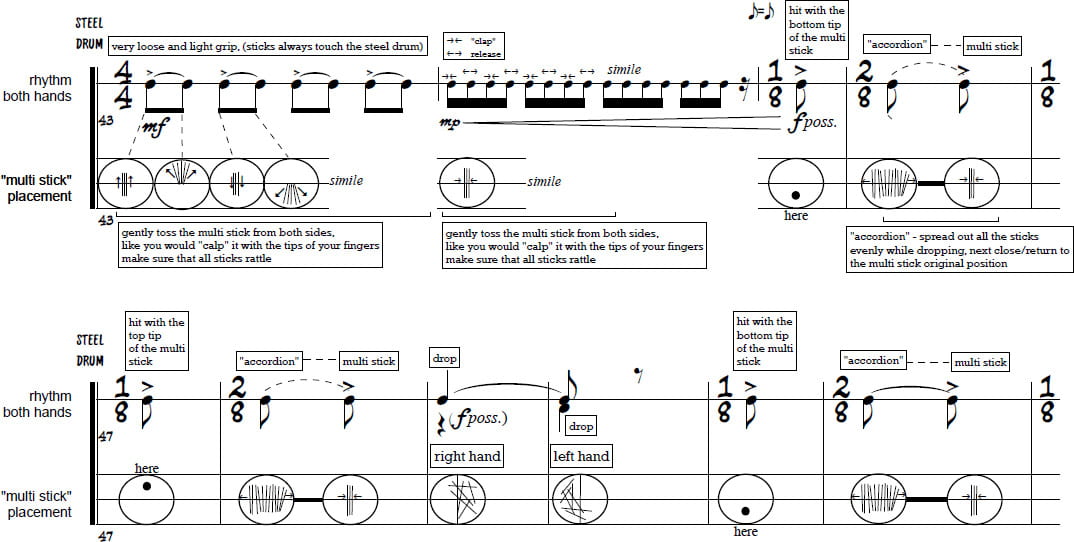

Blecharz’s fascination with both timbral qualities and the physical aspects of producing tones is reminiscent of Lachenmann’s musique concrète instrumentale, described by the German composer as music ‘in which the sound events are chosen and organized so that the manner in which they are generated is at least as important as the resultant acoustic qualities themselves.’4 Blecharz favors allusions to nature’s sounds, witnessed by audible breathing and panting, striking or tossing sticks onto a steel drum in K’an, the first of six distinct pieces within the opera, (Ex. 2), and rubbing or scratching hands and fingernails on the body, pegs, bridge, F holes, and other parts of an amplified cello in Map of tenderness (Ex. 3). His attentiveness to the acoustics of each space allowed viewers to hear multiple layers of sound simultaneously.

…

The difficulty of presenting Transcryptum elsewhere in its entirety without significant modifications will limit its dissemination and, potentially, the composer’s own emerging recognition in the broader musical world. Set pieces from the opera can be played independently, yet such performances lack any reference to the opera’s dramatic essence.5 Blecharz is not troubled by this situation. Indeed, his fondness for unconventionality undoubtedly factored into his decision to create Transcryptum as a site-specific piece. Moreover, his exploration of physical space and his affinity for technologically enhanced, multi-media performances attracted the interest of the younger generation, echoing the Warsaw Autumn Festival and Kraków’s Sacrum Profanum in their successful expansion beyond traditional concert venues and programs in recent years.

The difficulty of presenting Transcryptum elsewhere in its entirety without significant modifications will limit its dissemination and, potentially, the composer’s own emerging recognition in the broader musical world. Set pieces from the opera can be played independently, yet such performances lack any reference to the opera’s dramatic essence.5 Blecharz is not troubled by this situation. Indeed, his fondness for unconventionality undoubtedly factored into his decision to create Transcryptum as a site-specific piece. Moreover, his exploration of physical space and his affinity for technologically enhanced, multi-media performances attracted the interest of the younger generation, echoing the Warsaw Autumn Festival and Kraków’s Sacrum Profanum in their successful expansion beyond traditional concert venues and programs in recent years.

This production invites a conversation about the definition not only of opera and the implications of its location specificity, but also of the expectations of both audiences and performers at such events. Blecharz’s disavowal of many operatic conventions resulted in a production that relies on associations, yet invalidates many of those held by the typical operagoer. Transcryptum obliges viewers to make sense of a tightly scripted, yet seemingly disconnected group of events that occur in unusual spaces and are accompanied by unexpected sounds. Instead of enjoying a cohesive narrative from the relative comfort of an auditorium seat, they are forced to be engaged actively with the unfolding images and sounds. Comprehension is intentionally complicated by discomfort and confusion. Blecharz may have been inspired by Cage, Stockhausen, Lachenmann and others, but his creation is a novel contribution to the operatic genre that bears witness to the talent of a composer whose fame is rapidly spreading in contemporary music circles.

This production invites a conversation about the definition not only of opera and the implications of its location specificity, but also of the expectations of both audiences and performers at such events. Blecharz’s disavowal of many operatic conventions resulted in a production that relies on associations, yet invalidates many of those held by the typical operagoer. Transcryptum obliges viewers to make sense of a tightly scripted, yet seemingly disconnected group of events that occur in unusual spaces and are accompanied by unexpected sounds. Instead of enjoying a cohesive narrative from the relative comfort of an auditorium seat, they are forced to be engaged actively with the unfolding images and sounds. Comprehension is intentionally complicated by discomfort and confusion. Blecharz may have been inspired by Cage, Stockhausen, Lachenmann and others, but his creation is a novel contribution to the operatic genre that bears witness to the talent of a composer whose fame is rapidly spreading in contemporary music circles.

Projekt P is a part of Terytoria [Territories], a series of meetings with contemporary music in which the Polish National Opera seeks to discover and sketch a new image of opera. The genre is changing its definition today, conquering new territories, drawing new meanings, proposing a new aesthetic. The most recent Projekt P creations are Sławomir Kupczak’s Voyager and Katarzyna Głowicka’s Requiem For An Icon—these two chamber operas will be premiered in May 2015.

* * * * *

Notes & Author’s biography:

Cindy Bylander received her Ph.D. in musicology from The Ohio State University and currently resides in San Antonio, Texas. She was awarded a U.S. Fulbright grant to conduct research in Poland in the 1980s. She is particularly interested in the compositions of Krzysztof Penderecki, the impact of the Warsaw Autumn Festival and other regional festivals on musical life in Poland, and the roles played by the Polish Composers Union and its individual members as they negotiated the vicissitudes of Cold War cultural policies. Dr. Bylander has presented papers at conferences in the United States and Europe. She is the author of Krzysztof Penderecki: A Bio-Bibliography (Greenwood Press, 2004) and has published articles in Musical Quarterly (2012), Musicology Today (Warsaw University, 2010), “Warsaw Autumn” as a Realisation of Karol Szymanowski’s Vision of Modern Polish Music (Warsaw: Polish Music Information Centre 2007), Music of the Twentieth-Century Avant-Garde (Greenwood Press, 2002), Studies in Penderecki, Ruch Muzyczny, Polish Music Journal, and Polish Music Center Essays. Her article on Penderecki’s symphonies is forthcoming in Polish Music Since 1945 (Kraków: Musica Iagellonica).

(2) Andrew Clements, ‘Matchless inventions,’ The Guardian (23 May 2002), http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2002/may/24/shopping.artsfeatures1.

(3) His Phenotype for prepared and amplified violin (2012) calls for a bow made from 4 sheets of paper held together with scotch tape. Hypopnea (2010) is for detuned accordion. Blecharz received first prize in the 2007 Tadeusz Baird Young Composers Competition and a Warsaw Autumn Festival commission in 2012. He was also nominated for a Polityka Passport Award in 2012 as one of Poland’s most promising figures in classical music.

(4) “Musique concrète instrumentale, Helmut Lachenmann, in conversation with Gene Coleman (7 April 2008),” http://slought.org/content/11401/

(5) For ex., K’an and The Map of Tenderness were performed in Warsaw on 3 December 2013. http://allevents.in/warsaw/wojtek-blecharz-portret-kompozytorski-hellyeah/184161071776065