Polish Music Center Newsletter Vol. 10, no. 2

2004: Year Of Lutosławski

by Wanda Wilk

Polish Parliament has proclaimed 2004 as the year of Lutosławski in honor of the tenth anniversary of the late composer’s death on February 7th, 1994. Witold Lutosławski (1913-1994) was regarded as the greatest living composer of his time and was called the “Dean of Polish composers”. This title, in itself, was no mean feat, when you consider who were his contemporaries in Polish music: Górecki, Penderecki, Baird, Serocki and Bacewicz.

We in Los Angeles have been fortunate to have had Lutosławski visit us not once, but several times. In 1985 he honored us with his presence at the dedication of the Polish Music Reference Center (now the Polish Music Center). He recognized the importance of such a center with his magnanimous gift of five manuscripts in his own hand: Paroles tissées(1965), Preludes and Fugue (1972), Mi-parti (1976), Novelette (1979) and Mini-overture (1952). Soon other composers followed his example and donated their manuscripts to our Center.

We in Los Angeles have been fortunate to have had Lutosławski visit us not once, but several times. In 1985 he honored us with his presence at the dedication of the Polish Music Reference Center (now the Polish Music Center). He recognized the importance of such a center with his magnanimous gift of five manuscripts in his own hand: Paroles tissées(1965), Preludes and Fugue (1972), Mi-parti (1976), Novelette (1979) and Mini-overture (1952). Soon other composers followed his example and donated their manuscripts to our Center.

Lutosławski first came to Los Angeles in 1983 at the invitation of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. This began a love-affair between the orchestra and Lutosławski which lasted over a decade. At this first concert the composer was invited to conduct an entire program of his own works.

This evoked the following from Los Angeles Times music critic Martin Bernheimer: “A strange and marvelous thing happened at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion Thursday night. The Los Angeles Philharmonic, an organization hardly known for an adventurous spirit when it comes to serenading staid subscription audiences, devoted an entire winter season concert — repeat, an entire concert — to the music of Witold Lutosławski.”

This music critic, known for his sharp and caustic criticisms, went on to describe Lutosławski as, “a dauntless innovator, a probing musical philosopher and a forward-looking man of his time.” He continued:

He certainly does not write heart-rending melodies wrapped in slush-pump harmonies. He obviously refuses to court a potentially hostile public with easy effects or to reap the perverse pleasures of hand-me-down shock manuevers. The secret of Lutosławski’s enduring, and endearing, success may lie in his uncanny ability to use unabashedly progressive techniques to achieve unabashedly conservative ends.

Similar assessments were made throughout the decade by other music critics. John von Rhein of the Chicago Tribune wrote, “Lutosławski created a distinctive style in modern composition.” and Allan Kozinn of the New York Times titled his obituary, “Witold Lutosławski, 81, is Dead; Modern, yet Melodic Composer.” and described him, “as an innovative Polish composer whose orchestral and chamber works had a direct and immediate appeal that made them centerpieces of modern repertory.”

Since that historic concert in 1983, Lutosławski’s music has been performed many times by the L.A. Philharmonic and the composer, who only conducted his own music, returned four more times to conduct our local symphony orchestra: in 1989, 1991, 1992 and 1993. The program on March 3, 4 and 6 of 1983 featured the American premiere of Les Espaces du Sommeil for baritone and orchestra, the West Coast premiere of Novelette, and the first L.A. Music Center performance of Musique Funebre and Concerto for cello and orchestra.

In 1989 he conducted his Cello Concerto, this time with cellist Lynn Harrell, at the L.A. Philharmonic Institute Festival at UCLA. In 1991 he conducted the West Coast premiere of his Piano Concerto with Krystian Zimerman, for whom he wrote the concerto, as the soloist. At this time he also conducted the U.S. premiere of his Chantefleurs & Chantefables for a L.A. Philharmonic New Music Group program. In 1992 he again conducted the Cello Concerto along with Mi-Parti and Concerto for Orchestra. In 1993 he conducted the premiere of his Fourth Symphony, which had been commissioned by the L.A. Philharmonic. While the premiere was conducted by the composer himself in February, in October of that year, Esa-Pekka Salonen conducted (as described in the program) “Lutosławski’s magnificent Fourth Symphony, whose presentation by the Philharmonic last season proved one of the most highly acclaimed world premieres of an orchestral work within recent memory.” A year later in December Salonen included the Symphony during the orchestra’s tour in New York. The Fourth Symphony won Britain’s Classical Music Award in January 1994.

Earlier, Salonen had recorded Lutosławski’s Third Symphony, which had been commissioned by Sir George Solti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. This recording won not only a Grammy, but also a Cecilia Prize, a Koussevitzky Award and the 1986 Gramophone Award for Best Contemporary Record.

Lutosławski also composed a Fanfare for the 75th anniversary of the L.A. Philharmonic. He was able to hear this work performed in November 1993, when he stopped in L.A. for a week’s rest on his way to Japan to receive the Kyoto Prize. He had complained of being tired, but that’s all. Two months later, on February 7th, he died of cancer in his beloved Warsaw. Four days later the L.A. Philharmonic honored the memory of “this much-loved composer and friend” by beginning their regularly scheduled program with some choice words from Ernest Fleischmann, who ran the Philharmonic organization, and a special rendition of Grave for cello and piano by principal cellist, Ronald Leonard, and the scheduled pianist, Peter Frankl.

Lutosławski also composed a Fanfare for the 75th anniversary of the L.A. Philharmonic. He was able to hear this work performed in November 1993, when he stopped in L.A. for a week’s rest on his way to Japan to receive the Kyoto Prize. He had complained of being tired, but that’s all. Two months later, on February 7th, he died of cancer in his beloved Warsaw. Four days later the L.A. Philharmonic honored the memory of “this much-loved composer and friend” by beginning their regularly scheduled program with some choice words from Ernest Fleischmann, who ran the Philharmonic organization, and a special rendition of Grave for cello and piano by principal cellist, Ronald Leonard, and the scheduled pianist, Peter Frankl.

USC also honored Lutosławski that year with a special Memorial Concert organized by the Polish Music Center (with yours truly) and the USC Contemporary Music Ensemble’s director Donald Crockett, who had organized the music activities during Lutosławski’s two-week residency at USC in 1985. This November 1994 chamber music program included Epitaph for oboe and piano, the familiar Grave for cello and piano, Five Songswith words by Iłłakiewicz sung in Polish by mezzo-soprano Kathleen Rowland and Chain I. A video recording of the composer’s 1985 stay at USC was featured, along with a performance of Steven Stucky’s Boston Fancies for chamber ensemble. Stucky is an authority on Lutosławski whose own music shows the influence of the Polish master’s work.

Lutosławski’s death brought out much praise from all sources. Composer Marta Ptaszynska, who how lives in the U.S., wrote a full-page article in Polish for Nowy Dziennik on February 17th. She called him the greatest “creator of his times.” She also wrote of his humble and elegant demeanor. He was greatly revered in Poland. Polish author Zdzisław Sierpinski wrote in August 1995 of the profound respect all Polish composers had for the great maestro and how terribly empty Polish musical life in Poland was without him.

In 1996 Mark Swed wrote a review of a Sony recording of Lutosławski’s Piano Concerto and other musical works with the L.A. Philharmonic. He called him the “Third Great Polish Composer”, after Chopin and Szymanowski. He also wrote that the Piano Concerto, begun in the 1970s and finally finished in 1987, “ultimately counts as one of the late, most mature works of the composer…everything about the score reveals the stamp of a master.”

Ivon Humphreys of the British music journal Gramophone wrote in December 1994 that, “Lutosławski’s death ended a career which produced some of the finest and most musically challenging scores of the century.” In 1988 Lutosławski won First Place in Contemporary Music for a Phillips recording of his Cello Concerto and his Concerto for Oboe, Harp & Chamber Orchestra with the composer conducting the Bavarian Radio Symphony.

BBC magazine called him a “rigorous individualist” who, “had the manners and demeanour of an older, more gracious age; but he wrote music of sufficient originality to assure him a prominent place in the late-20th-century canon.” Ernest Fleischman, former artistic director of the L.A. Philharmonic, called him a “giant of this century” and claimed, “his innovations and progressive techniques in composition will be carried on by generations of younger composers.”

Lutosławski was admired and respected by his peers all over the world. When martial law was declared in Poland in 1981 and Lutosławski was not allowed to leave the country for a concert engagement in Germany, the government of that country intervened on his behalf and he was allowed to go.

Lutosławski was respected not only for his music but also for his personality, which has been described as gracious and humble. He spoke several languages fluently and thus communication was easy with him. His English was impeccable and spoken with a distinct British accent. He never wrote an opera, but instead wrote vocal/orchestral music to French and Polish poems. He was well-educated, having studied mathematics and philosophy at the university and studied and played both the piano and violin extremely well. He wrote several good works for stringed instruments, one for famous violinist Sophie Mutter and the other for cellist Mtislav Rostropovich.

His mathematics background helped him to compose in an orderly manner and enabled him to discover a new way to compose in the 1980s. He described this new musical form, which he called a chain, as, “two independent layers put together. The sections inside these layers begin and end at different times.” Since 1948 he had searched for his own sound language. No matter where he was he spent at least one hour each morning before breakfast writing down various tonal combinations on paper.

In addition to working on this “chain” in music, Lutosławski also experimented with the elements of chance introduced by American composer John Cage. However, Lutosławski never gave up control of the music to the players; his was controlled “aleotoric” music. He gave specific instructions and this in turn ensured that the music did not sound different every time it was played by a different group of artists.

As a person he was well-mannered, gracious and unpretentious. He wanted to be called “Witek” and not Mr. Lutosławski. Having been raised to respect one’s elders, I found this very hard to do. Actually, he was only eight years older, but it was his station and position in the music world that had an effect on me.

When Lutosławski died in 1994, USC professor of composition Donald Crockett said this:

Put simply, Witold Lutosławski was the most inspirational composer I have ever met. His music, which is strong, clear, lyrical, serene, highly personal and innovative, will endure. To have been able to work with Witold Lutosławski, to conduct his music and to get to know him a little, was my great fortune. I join the entire musical world in missing him dearly.”

Poland has already ensured that Lutosławski’s name will remain for posterity by naming the music studio at Polish Radio the Witold Lutosławski Concert Studio in 1996 with a gala inauguration ceremony at which an unveiling of a commemorative plaque, an exhibition and a symphony concert took place. The famed Antoni Wit conducted the Polish Radio National Symphony Orchestra. The concert program book issued in both Polish and English text included an article by Martina Homma on sketches for “Trois poèmes d’Henri Michaux” – the result of research done by the Polish musicologist under the guidance of the great maestro. In 1995 the Warsaw Philharmonic inaugurated an annual International Composer’s Competition bearing his name. There is also a Lutosławski International Cello Competition. See www.vin.pl.

During his lifetime Lutosławski was honored with many prizes and honorary degrees. Today it is his music that continues to be honored. The Los Angeles Philharmonic continues its love affair with Lutosławski. A few years ago when the Philharmonic orchestra performed the Fourth Symphony again, the conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen made an unprecedented pause in the program, faced the audience and told them that this symphony was “their” symphony and that it held a special place in their hearts. Last October, the Philharmonic’s new home, Walt Disney Hall, celebrated its opening with three gala concerts. Lutosławski’s Cello Concerto was selected for the second one and renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma was the soloist. Although this giant in contemporary classical music is gone, his music endures and his symphonic works are already treated as “classics” of the modern repertoire. We salute Poland’s “Third Great Composer” in this Year of Lutosławski!

During his lifetime Lutosławski was honored with many prizes and honorary degrees. Today it is his music that continues to be honored. The Los Angeles Philharmonic continues its love affair with Lutosławski. A few years ago when the Philharmonic orchestra performed the Fourth Symphony again, the conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen made an unprecedented pause in the program, faced the audience and told them that this symphony was “their” symphony and that it held a special place in their hearts. Last October, the Philharmonic’s new home, Walt Disney Hall, celebrated its opening with three gala concerts. Lutosławski’s Cello Concerto was selected for the second one and renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma was the soloist. Although this giant in contemporary classical music is gone, his music endures and his symphonic works are already treated as “classics” of the modern repertoire. We salute Poland’s “Third Great Composer” in this Year of Lutosławski!

News

Kulenty Flute Concerto Premiere

The Flute Concerto No. 1 (for Microtonal Flute, Winds and Percussion) of composer Hanna Kulenty will have its American debut on March 4, 2004 at the 10th Annual Other Minds New Music Festival. This year, the Other Minds Music Festival will take place from March 4-6 at the Yerba Buena Center, San Francisco.

The Flute Concerto No. 1 (for Microtonal Flute, Winds and Percussion) of composer Hanna Kulenty will have its American debut on March 4, 2004 at the 10th Annual Other Minds New Music Festival. This year, the Other Minds Music Festival will take place from March 4-6 at the Yerba Buena Center, San Francisco.

The Other Minds Festival is a Composer-to-Composer Festival, meaning that the major participants (prominent 20th century composers and scholars chosen from diverse stylistic and cultural backgrounds) meet privately for four days. They meet in locations of great natural beauty and isolation, which casts a surprising hue of receptivity on the participants and opens their senses to new ideas. They then return to San Francisco and speak to a larger group of conference registrants. For more information or to purchase tickets, visit www.otherminds.org.

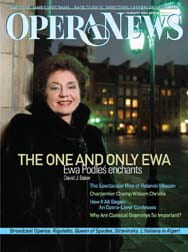

Podleś In Opera News

Polish contralto Ewa Podleś has long been known to Polish audiences as a concert singer with a beautifully agile voice, an astounding range and phenomenal stage presence and skill. As the February cover article of one of America’s most prestigious opera magazines, the Metropolitan Opera’s Opera News, tells us, Ms. Podleś is now taking on more opera roles and world-wide audiences. Having recovered from a broken arm sustained during her last trip to the U.S. and having sung her West Coast debut concert (see report in the January newsletter), she is busy with several opera roles east of the Mississippi. She recently sang Ulrica in Un Ballo en Maschera at the Michigan Opera Theater, where she was thrilled to work with a director who was both thoroughly professional and willing to listen to her ideas. Together they shaped a character that was ragged, “a seer who suffers the burden of her gift,” rather than young and sexy, as other company’s have had her portray Ulrica. Although some directors and conductors may see her willingness, nay demand, to be a part of the creative process as a hindrance to their own vision, few can dampen her spirit and most see it as, “a certain integrity that sets her apart.” (David DiChiera, MI Opera Theater’s general director)

Polish contralto Ewa Podleś has long been known to Polish audiences as a concert singer with a beautifully agile voice, an astounding range and phenomenal stage presence and skill. As the February cover article of one of America’s most prestigious opera magazines, the Metropolitan Opera’s Opera News, tells us, Ms. Podleś is now taking on more opera roles and world-wide audiences. Having recovered from a broken arm sustained during her last trip to the U.S. and having sung her West Coast debut concert (see report in the January newsletter), she is busy with several opera roles east of the Mississippi. She recently sang Ulrica in Un Ballo en Maschera at the Michigan Opera Theater, where she was thrilled to work with a director who was both thoroughly professional and willing to listen to her ideas. Together they shaped a character that was ragged, “a seer who suffers the burden of her gift,” rather than young and sexy, as other company’s have had her portray Ulrica. Although some directors and conductors may see her willingness, nay demand, to be a part of the creative process as a hindrance to their own vision, few can dampen her spirit and most see it as, “a certain integrity that sets her apart.” (David DiChiera, MI Opera Theater’s general director)

Ms. Podleś is currently in production of Verdi’s Don Carlo at the Opera Company of Philadelphia (30 Jan. – 15 Feb.). She will give a concert performance of Ulrica in Un Ballo en Maschera by Verdi at Carnegie Hall in March, and then will be performing Azucena from Verdi’s Il Trovatore at the Florentine Opera in Milwaukee. In addition to her opera performances, Ms. Podleś has several concert performances coming up (see Calendar of Events below). She also has plans for more CD recordings. Although her recent explorations of Verdi and opera in America seem to indicate a turning point in her career, Ms. Podleś is hesitant to discuss the future and, for example, whether it will include a role at the Met. (She has given one limited performance with the Met in the past.)

This article was based on the editorial, “Mission Accomplished,” by F. Paul Driscoll and the article, “The Podleś Principles,” by David J. Baker, from the February 2004 issue of Opera News, vol. 68 no. 8. To read the full articles, visit www.operanews.com.

Mischakoff Anniversary

February 1st marks the anniversary of the death of one of Russia’s great violinists, Mischa Mischakoff (1895-1981). After leaving Russia, Mischakoff delighted audiences in Poland and the U.S. as concertmaster and soloist. To learn about this great virtuoso, please see Joseph Herter’s article in the January newsletter, which reinstates Mischakoff into the musical memories of the many orchestras and audiences he served in his lifetime. A slightly shorter version of this article will be published in Polish in the March issue of MUZYKA 21.

February 1st marks the anniversary of the death of one of Russia’s great violinists, Mischa Mischakoff (1895-1981). After leaving Russia, Mischakoff delighted audiences in Poland and the U.S. as concertmaster and soloist. To learn about this great virtuoso, please see Joseph Herter’s article in the January newsletter, which reinstates Mischakoff into the musical memories of the many orchestras and audiences he served in his lifetime. A slightly shorter version of this article will be published in Polish in the March issue of MUZYKA 21.

Skrzypczak Premieres

Polish composer Bettina Skrzypczak was born in Poznań, Poland. She studied piano, musicology and composition at the Music Academy there, as well as studying with Lutosławski, Pousseur, Nono and Xenakis at Kazimierz, the “Polish Darmstadt”. Musically speaking, Skrzypczak views the world as “ordered chaos”; to extract the sonic order from this chaos, she tends towards mathematical processes similar to those of Iannis Xenakis. According to Max Nyffeler, the result is as follows: “The polarisation of the material’s innate dynamics and their subjective projection results in a gravitational field within which sound appears as a fluctuating, constantly changing continuum, charged by a vital stream of energy, and, in concrete technical terms, often requiring a high level of collective virtuosity from the performers.”

Even in Switzerland, where she now resides and participates fully in the musical culture, Skrzypczak has maintained close ties with her Polish roots. Poland was where she first studied music and she returned again in the late 1990s to complete a doctorate in music and philosophy in Krakow. While she often writes in places and for audiences outside of Poland, one can hear the influence of the Polish modernist tradition in her music.

The next few months will be an exciting time for this composer. In un soffio for Wind Quintet will be premiered on Monday, February 2nd, in Basel. The work will be played by the Arion Quintet Basel (Isabelle Schnöller, flute; Curzio Petraglio, clarinet; Matthias Arter, oboe; Matthias Bühlmann, bassoon; Lorenz Raths, horn) and was commissioned by the Basel Chamber Music Society. The String Quartet no. 4 will be premiered on April 2nd, as a ballet production. This performance will be a cooperation between the composer, the choreographer Martino Müller from the Basel Ballet and the young Amar Quartet playing on stage as a part of the scene.

Information for this article was taken from the Portrait of Bettina Skrzypczak, written by Max Nyffeler, featured on the composer’s website, www.bettina-skrzypczak.com/.

Kohan In Hall Of Fame

The editor of the Polish American Journal, the largest English- language monthly newspaper dedicated to Polish American heritage, was inducted into the Buffalo Music Hall of Fame at a ceremony last November. Mark Kohan was recognized for his work as the leader of the Steel City Brass, one of western New York’s most prominent polka bands. The Polish American weekly “Straz” stated that he is, “highly regarded within American Polonia for his expertise on not only the polka, its history and derivations, but also as a Polish and Polish- American historian.” His band has released five LPs and specializes in music for Polish-American functions. In addition, Kohan was project coordinator for several New York State Council on the Arts’ recording projects including “Polkas for children” and “A Kolberg Sampler.”

Wroński International Violin Competition

Tadeusz Wroński (1915-2000) was an exceptional violinist and simultaneously one of the world’s most famous violin teachers. He graduated from the Warsaw Conservatory in 1939, where he studied under professor Józef Jarzębski. In 1947-48 he continued his musical education under professor Andre Gerttler at the Brussels Conservatory. He was a professor and the rector at Warsaw’s State Higher School of Music (currently the Frederick Chopin Academy of Music) and he taught at the largest music college in the United States, the Indiana Bloomington School of Music, from 1966-1984. During his career, he educated over five hundred violinists.

The Wroński Competition is sponsored by the Frederick Chopin Academy of Music and will be held on February 1-8, 2004. The first competition was held in Warsaw on January 8-9, 1990. This year’s edition has drawn forty-five young violinists from China, France, Holland, Japan, Kazakhstan, South Korea, Germany, Poland, Russia, Romania, and Hungary. The competition jury, made up of violin virtuosos from six countries, will be chaired by renowned Polish violinist Magdalena Rezler-Niesiolowska, herself formerly a student of professor Tadeusz Wroński.

Additional information is available from Slawomir Tomasik, tel. (+48 22) 615 26 52, 0-606 581 547 and at www.chopin.edu.pl.

Paderewski Festival

Paderewski Festival: Plays-Pianos-Presentations is an international event in upstate New York celebrating one of the greatest figures of the 20th century: Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Paderewski (1860-1941) was a pianist virtuoso, composer, statesman, and philanthropist — a noble, generous, and good human being who significantly impacted life in his native Poland and in America. He is one of the greatest figures of the 20th Century, having profoundly influenced the history of Poland, the history of music, and, indeed, the history of culture on a global scale. Even his contemporaries called him “immortal.” But who, really, was Paderewski? Who is he for us today? How can he help us to live better lives? What do we owe him? These questions will be considered at the Paderewski Festival through the media of music (including performances by Igor Lipinski, recipient of the Grand Prix for Young Pianists at the Paderewski Festival in Kasna, Poland), visual art (including the exhibit Paderewski: Portrait of a Musician, on loan from the PMC, Maja Trochimczyk, curator), theater (including puppeteering and the play Paderewski’s Childrenby Kazimierz Braun), and more. For further information and a complete schedule of events, visit www.wnypolonia.com/polfound or contact the Paderewski Festival Chairperson, Robert J. Fronckowiak at (716) 677-2726.

Forte And Her Polish Students

The ranks of international friends of Polish music are steadily increasing. Pianist Madeleine Forte who teaches at Yale University, has issued a CD with Chopin’s music and has two wonderful Polish students who have now graduated from her class).

Forte’s Chopin recording, on an Erard Piano from 1881, at the Yale Collection of Musical Instruments, was issued on Romeo Records 7214 and is available from Qualiton Imports, Ltd., fax: 718-729-3239, email: qualiton@qualiton.com. The recording includes Ballade No. 4, Etude Op. 25/6, Etude, Op. 10/5; Nocturne, Op. 15/1, Nocturne, Op. 55, 2; Barcarolle, Op. 60; Preludes Op. 28, nos 13-18; Prelude, Op. 45; Mazurkas Op. 17, nos 2-3; and Polonaise, Op. 53. The pianist considers Chopin’s music to be crucial to French musical culture, because of its wide-ranging and long-lasting influence on French composers, including Ravel, Fauré and Debussy.

Forte’s previous Chopin recordings received rave reviews from the New Yorker, Clavier, American Record Guide and Fanfare. She was praised for “gorgeous tone and sensuous line” and her Chopin interpretations were considered “elegant” (New Yorker), “outstanding” (Clavier), “generous and polished (Turok’s Choice), reminding listeners of Artur Rubinstein (ARG). Fanfare called her performances “nuanced, controlled, and unaffected . . . with a full bodied tone, with great power and even majesty.” Her previous recording of Bartok, Barber, Liszt and Beethoven was highly praised in Fanfare for her “Exceptional control of textures” “remarkable transparency” and “unique personal style.” According to Fanfare, she is “a notable colorist, fully alert to the shadings of the music and (an even more rare skill) able to trace out the mood swings of the program. . . even at its peaks of high romantic intensity, the playing remains refreshingly direct.” For more information on Forte, please visit her web page at www.madeleineforte.com.

Her love of Chopin’s music translated into her teaching and selection of Polish students for her class. Two notable young pianists recently started their professional careers and we’d like to introduce these pianists to our readers.

Pianist Anna Kijanowska has distinguished herself internationally as a recitalist, chamber player and concerto soloist. Appearances this year have included a recital at the Szymanowski Museum in her native Poland, concertos with the Kiev and Czernigov Philharmonic Orchestra in Ukraine, and several solo recitals in the New York Metropolitan area. She has received numerous prizes, including First Prize in the MTNA Northern Division Competition, and scholarships, from the Kosciuszko Foundation and the Manhattan School of Music among others, in recognition of her skill.

Ms. Kijanowska began her musical education in Poland at the age of seven, and gave her first recital the following year. After receiving her Master of Music Degree in Piano Performance and Piano Pedagogy from the Wroclaw Music Academy, Ms. Kijanowska was invited by Dr. Madeleine Hsu (Forte) to the United States. She holds a Doctorate and Master of Music degree in Piano Performance from the Manhattan School of Music, where she studied under the tutelage of Byron Janis and Mykola Suk.

In 1997, Mrs. Anna Rutkowska-Schock was awarded a scholarship to attend Boise State University by Dr. Madeleine Hsu Forte, and studied for a Bachelor’s degree under Dr. Hsu. She also studied at Boise State under Dr. James Cook. During her studies at Boise State she won the Concerto Aria Competition, and after just one and a half years, received a Bachelor of Arts degree in Piano Performance. At present, she gives solo and chamber recitals and regularly works as an accompanist for the K. Lipinski Academy of Music in Wroclaw.

In June 2001, Mrs. Rutkowska-Schock graduated with a Master of Arts degree with honors from the K. Lipinski Academy of Music in Wroclaw, Poland. In 2002-03, she also received awards for Best Accompanist from 2 national vocal competitions in Poland. She was invited to accompany singers and instrumentalist during the IBLA International Music Competition in Sicily in 2003 and was awarded the Best Accompanist award with special mention for her performance of C. Franck’s Sonata for Violin and Piano. As the recipient of this award, she has been invited to take part in an international concert tour which is crowned by performances at New York University and Carnegie Recital Hall at the beginning of 2004.

Baltic Voices

The Seattle Chamber Players is proud to announce Icebreaker II: Baltic Voices — a three-day international festival and conference of contemporary music from the countries that surround the Baltic Sea: Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia and Sweden. The festival will take place from February 13-15, 2004, at Benaroya Hall in downtown Seattle.

Curated by noted musicologist Dr. Elena Dubinets, the festival has two key components. First, the Seattle Chamber Players will perform music of contemporary composers from all nine countries of the Baltic Sea region; and second, the festival will involve an educational component: a musicological symposium on the problems of contemporary Baltic music. An important feature of the festival will be the inclusion of internationally prominent musicologists from the countries represented. These leading musicologists will give presentations about the contemporary music scenes of their countries, and the composers will present their own music in additional one-hour seminars.

For more information, visit: www.seattlechamberplayers.org.

Obituary

Czesław Niemen, née Wydrzycki, was born in 1939. Niemen was a popular singer, composer, instrumentalist and sculpture. His most famous songs were: Pod papugami[Beneath the parrots], Czy mnie jeszcze pamiętasz [Do you still remember me], Dziwny jest ten świat [This world is strange] and Sen o Warszawie [Dream about Warsaw].

Paderewski And Chant D’amour

An Essay for Valentine’s Day by Maja Trochimczyk

The phenomenon of the “immortal Paderewski” surrounded by the adulation of crowds of his female listeners emerged during the young pianist’s first British tours in 1890. In May and June that year Paderewski gave his first London concerts; he also sat for a series of portraits, including two by the most important members of British pre-Raphaelite and Aestheticism movements, Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) and Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912). The 1890 silver-point drawing by Burne-Jones resembled a profile photograph of Paderewski used for promotion during his concert tours at that time. The drawing repeatedly appeared in Paderewski’s promotional literature including numerous magazine covers, such as the cover of The Etude magazine from 1915 reproduced below. (Paderewski was 55 at that time, and certainly did not look like a blushing youth as depicted here).

By 1895, the Paderewski recital assumed its final form, unchanged through the remainder of the composer’s career. A lone spotlight highlighted the golden hair of the pianist at the center of the stage. The concert hall was shrouded in darkness and emptied of sensory stimuli other than Paderewski’s piano, heard in hushed silence. It is interesting to note that a report from Paderewski’s 1895 concerts in Paris mentions the “brilliance of electric light” as a characteristic trait of his recital there. In contemporaneous America, this brilliance gave way to a mysterious darkness. Furthermore, Paderewski enjoyed performing for audiences whose love for the music and concentration on his artistry was palpable through their silence. In his Memoirs he twice mentioned giving recitals in the home of a certain Mrs. Bliss of Santa Barbara, whose “love and appreciation of music were very rare. To play in her house was an experience unlike anything else I found — it was like celebrating a Mass. The atmosphere of silence was like that of a temple. It was beautiful and inspiring.”

The pianist, a lone focal point for his listeners, also revealed his “playful” side by capricious changes of the program depending on his mood, by arriving late, or by interrupting performances in response to the slightest disturbances in the concert hall. He overwhelmed and exhausted his audiences by mammoth programs of twelve to seventeen pieces, up to three hours of music, including as many as five to seven encores. He did not allow anyone to come in or leave the hall while he was playing in order to maintain his focus and preserve the “sacred” atmosphere that transformed his performances into artistic rituals. Praised for his personal charisma, Paderewski knew how to direct his emotional energy towards those who seemed indifferent and distracted at first. Of course, there were few and far between absent-minded listeners at his recitals; his attendees were his faithful. The pianist offered the following description of his audiences in The Paderewski Memoirs (p. 277):

The pianist, a lone focal point for his listeners, also revealed his “playful” side by capricious changes of the program depending on his mood, by arriving late, or by interrupting performances in response to the slightest disturbances in the concert hall. He overwhelmed and exhausted his audiences by mammoth programs of twelve to seventeen pieces, up to three hours of music, including as many as five to seven encores. He did not allow anyone to come in or leave the hall while he was playing in order to maintain his focus and preserve the “sacred” atmosphere that transformed his performances into artistic rituals. Praised for his personal charisma, Paderewski knew how to direct his emotional energy towards those who seemed indifferent and distracted at first. Of course, there were few and far between absent-minded listeners at his recitals; his attendees were his faithful. The pianist offered the following description of his audiences in The Paderewski Memoirs (p. 277):

I think that an audience is like a colossal collective individual, and primitive to the excess. It is never guided by reasoning, but always by intuition, by feeling and instinct. Audiences, no matter how large (the larger the more so), feel just like a collective personality; they always feel whether the one to whom they show their sentiment loves them or not. I have always loved them, and I love them still — the thousands I have played for through the long years.

Paderewski’s selection of his repertoire contributed to the creation of his beautified image as a timeless messenger of love. His choice of love-themed compositions also served this purpose. Paderewski selected such sentimental music to please his female audiences, with the unexpected result of being censured by the male music critics who expressed impatience with his tendency to engage in “crowd-pleasing” sentimentality. His concert repertoire featured a variety of small “romantic” forms, especially transcriptions of seminal excerpts from Wagner’s apotheosis of eternal love, Tristan und Isolde — the Prelude(transcribed by Paderewski’s student, Ernest Schelling) and Isolde’s Liebestod (arranged by Liszt). When heard now, due to the dearth of better recordings, these staples of overwrought romanticism sound quite horrid, indeed. Yet, with the flowing melodies, passionate themes of ecstasy and eternal love-to-death, and ambiguous sequences of unsolved dissonances, these works are suffused with love symbolism and we may only imagine the impact they had on the female listeners.

Women crowded his concerts, eager for a glimpse of Paderewski’s “immortal beauty.” TheNew York Daily Tribune noted that at the final concert of his first American tour, held at Carnegie Hall on March 26, 1892, “the cult of Paderewski” reached a new stage: “It became a crazied fashion, not responding either to reason, to common sense, nor to the sense of Justice.” The New York Times reported from the Carnegie Hall recital of 9 November 1895 that “women were turned towards him in positions of such zealous devotion that it could be assumed that fanatics listen to a sermon of a prophet of a new religion.” The Paderewski cult or “craze” continued, practically undiminished, until World War I. In November 1907, Olin Downes (1886-1955), the music critic of The New York Times thus described a Paderewski recital held on November 6, with a program including Paderewski, Beethoven, Chopin, Liszt, and Zygmunt Stojowski’s Chant d’amour:

A Paderewski recital — seance might be a better word — is an occasion that requires no signboard to identify. The crowded stage, the roped-in piano, the scurrying ushers, the excited twittering of the ladies, the matinee miss and her confidential friend, the whole rows of female colleges — for is not the mighty one meat and drink and bon-bons to them? — and finally, on the pianist’s appearance, that species of hushed applause that voices the general spirit of reverential suspense and expectation — all these things combine to impart an atmosphere of rare novelty peculiar to the occasion. It might well be asked “Why this?” in these days of the Liszt rhapsody, of tiddling Chopinzees, of piano poets, prophets, and pedants, in short, in an age which provides every variety of knight of the keyboard. There is one explanation, and only one. It lies in the recognition of that subtle, elusive, indescribable essence that for want of a better term is usually called “personality.” That vital spark that made possible a Paganini and a Liszt, that has enabled this Pole to enthrall and subjugate his audiences until whatever he does, they cry “Ave imperator!”

Other aspects of Paderewski’s skill as a performer come to the fore in an account written several years later by a female listener, Nellie Cameron Bates, who described herself as a “country girl” and attended a recital by Paderewski in 1914. The report comes from a later phase in Paderewski’s tours, just prior to the outbreak of World War I, but reflects the subjective response of one member of his female audience that typifies the Paderewski cult begun twenty years earlier.

There was music to see as well as hear! Oh! the poetry and grace of the swiftly flying supple hands and the ever-moving feet! Sometimes his arms were lifted as high as his head; sometimes they glided on the surface of the keys like foam on the waves, but always with absolute ease and precision. And the music! You soon forgot to note the amazing technic, the endless variety of tone quality, the kaleidoscopic change of effects. You felt only that a great soul was speaking to you and drawing you close to the heart of life. He was opening God’s great book of human life for you and letting you read the pathos, the grandeur, the terror, the hope, the joy, the love which lie deep in the heart of this life of ours. You heard that song which has pulsed for so many years — old, old as the world and yet, forever new.

The words of Nellie Cameron Bates echo some sentiments from Paderewski reviews, emphasizing the emotional fulfillment and spiritual illumination awaiting the devoted listeners at their Master’s recitals. Bates wrote in first person, describing the music, heard in a public recital as communicating intimately and directly with her inner self. This immediacy of an individual experience suspended the awareness of the external world and transformed attending a piano recital into a quasi-religious occasion. Bates’s description of her state of mind during the concert (and the preceding narrative of traveling to this concert as if it were a pilgrimage) is a document of a Paderewski cult that had spawned forms of cultural expression virtually unchanged since its inception in 1891 until World War I. She may be considered an exemplar of a cultural phenomenon — young female fans of his music and artistry — dubbed by the press the “Paderewski girl.” Their enthusiasm for the handsome pianist took many unusual forms (attacking him with scissors to clip his hair, stalking him, crowding around him after concerts, demanding never-ending encores, etc.).

The listeners’ frenzy sometimes put the object of all this devotion in danger. The Polish periodical Scena i Sztuka [Stage and Art] reported in April 1908 that after Paderewski’s recital in San Francisco on 1 March 1908, the virtuoso was virtually mobbed by his female admirers:

During the concert in San Francisco, Paderewski was so ardently admired by his audience, that ladies and misses filled with delight threw themselves upon the artist to congratulate him and shake his hand. In the crowd, Paderewski lost his breath and nearly fainted. He was liberated with the greatest difficulty. After being taken to the hotel, he suffered a nervous breakdown, following which he had to rest for several days.

An ultra-romantic addition to Paderewski’s repertoire, Zygmunt Stojowski’s Chant d’amour, may have served as an important stimulus for this frenzy of enthusiasm. The San Francisco program included also works by Paderewski (Variations and Fugue in E-flat minor), Beethoven (Sonata in E-flat major Op. 27 No. 1), and Chopin (Two Nocturnes Op. 15; the whole Op. 10 of his Etudes, and Scherzo in B-flat minor Op. 31). Three arrangements of Schubert’s songs by Liszt complemented the concert that ended, as most Paderewski recitals, with the “tonal typhoons” of one of Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies (this time no. 13). The scope of the program and its sheer size could make one swoon and faint; no wonder that mass hysteria of female listeners occurred at this, and many other concerts given by Paderewski.

The author of Chant d’amour, Op. 26, No. 3, Zygmunt Stojowski (1870-1946), was Paderewski’s friend and associate: a fellow Pole and an immigrant to America (see the biography by Joseph Herter in Polish Music Journal 5, no. 2). Chant d’amour, first published in Europe in 1903 (in America in 1907), appeared on Paderewski’s concert programs between 1899 and 1931 and was publicly heard over eighty times between its premiere on 2 May 1899 at the Erard Hall in Paris and its final performances during the 1931 American tour. The work was one of the featured compositions for Paderewski’s 1907-08 American concerts. Its polished tranquility and dreamlike sweetness of emotion destined this miniature to become one of the musical symbols of the artist who was greeted by his female public as a living embodiment of Love, Art and Beauty. Paderewski recorded Chant d’amour on 11 December 1926 on Victor 6633.

The author of Chant d’amour, Op. 26, No. 3, Zygmunt Stojowski (1870-1946), was Paderewski’s friend and associate: a fellow Pole and an immigrant to America (see the biography by Joseph Herter in Polish Music Journal 5, no. 2). Chant d’amour, first published in Europe in 1903 (in America in 1907), appeared on Paderewski’s concert programs between 1899 and 1931 and was publicly heard over eighty times between its premiere on 2 May 1899 at the Erard Hall in Paris and its final performances during the 1931 American tour. The work was one of the featured compositions for Paderewski’s 1907-08 American concerts. Its polished tranquility and dreamlike sweetness of emotion destined this miniature to become one of the musical symbols of the artist who was greeted by his female public as a living embodiment of Love, Art and Beauty. Paderewski recorded Chant d’amour on 11 December 1926 on Victor 6633.

The intended amorous content of Chant d’amour is indicated by the work’s cover of the 1908 Schirmer edition, featuring a stylized image of a loving couple surrounded by music in a 18th-century pastoral landscape. In 1907, after its New York premiere Olin Downes described Chant d’amour as merely “a pleasant parlor piece with harmonic reminiscences of Chopin’s E-minor Prelude.” However, its “singing” tone, sequentially ascending melody, and a variety of expressive and narrative symbols, place this composition in entirely different company, that is the “love-themed” music found in Paderewski’s repertoire. The work features such staple gestures of romantic music as flowing melodic lines and appoggiaturas, tension-inducing sequences, and tranquil, repeated accompaniment figures.

The “love-duet” characteristics of the Chant d’amour were first noticed by the music critic Henry E. Krehbiel. He described Chant d’amour in his “Analytical Notes on Mr. Paderewski’s Programmes” (reprinted in Polish Music Journal 4, no. 2, 2001) prepared for the pianist’s American tour of 1907 in the following way:

The piece is in the key of G-flat, and is marked by a formal feature of an original nature: The principal melody dies away in a cadenza in D-flat which leads to a middle part of a duet-like character, which, after working itself up to an impassioned climax, gives way to a return of the first theme by means of the same cadenza, this time in G-flat.

Paderewski’s recording of Chant d’amour, besides the usual flexibility of rhythm and exaggerated rubato (as well as much faster tempo than could be expected from the marking of Andante), features one textural change. The final two tonic triads in G-flat are shifted an octave higher. Thus, instead of a definite closure with morendo tranquility, the Chant d’amour ascends into the silence. The singing tone quality, so important in establishing the “narrativity” of Chant d’amour, was one of the main characteristics of Paderewski’s piano technique. Throughout his career, starting from the earliest concerts in Buffalo in 1892, reviewers emphasized his “singing tone.” On 18 February 1982, the Milwaukee Sentinelwrote that “his use of pedals is free and continuous; it creates marvelous effects. With their assistance he sings at the piano…” Paderewski often emphasized the significance of pedaling in the accomplishment of the singing tone quality; his remarks on this subject appear, for instance, in The Paderewski Memoirs (p. 329) where he states:

The pedal is the strongest factor in musical expression at the piano, because first of all it is the only means of prolonging the sound. The piano is a percussion instrument, you know, and the only way of making it appear prolonged is the pedal… Whenever learning a new piece, one must learn also the proper effect of the pedaling. Each new piece requires a new pedaling, adaptable to the character of the music.

It would be easy to ascribe the presence of Stojowski’s Chant d’amour in Paderewski’s repertoire to a gesture of collegiality: according to Stojowski’s biographer Joseph A. Herter (see Polish Music Journal, vol. 5, no. 2, 2002), Paderewski generously introduced his younger colleague to American audiences in order to help him establish himself as a professional music teacher, composer, and concert pianist. This purpose, though, could be served by any other work from Stojowski’s profuse output of solo piano pieces, not necessarily by the Song of Love. By adding this work to the repertoire in 1907, Paderewski stimulated the cult of his artistic persona as the “archangel” with golden hair and a sweet message of ecstatic fulfillment in pure emotion. He could have replaced it with his own composition of the same title, Chant d’amour from Op. 10 no. 2 (published in the U.S. in 1904 by G. Schirmer, New York). However, this work did not frequently appear in Paderewski’s concert repertoire. It is easy to observe that the formal model for Songs of Love by Paderewski and Stojowski was the genre of the nocturne. The outer sections of the ABA’ form in the Paderewski piece are to be played lento con sentimento while the middle one, where the feelings stirred and the texture thickened into parallel octaves and chords is marked animato ed appassionato.

A toned-down version of Stojowski’s three-partite sentimental gem (actually, being composed earlier, it provided the model for Stojowski’s more sophisticated and virtuosic composition), Paderewski’s Chant d’amour is a lesson in the use of the pedal to accomplish a singing quality. The long-lasting resonance of the piano with the pedal may be linked to the “inwardness” of emotional experience and a contemplative mood associated with the fantasy of perfect love. Yet, the miniature is not accomplished or refined enough to be presented in public. Thanks to this publication, Paderewski’s admirers had an accessible “take-home” version of the Songs of Love and Death that transported them into heavenly realms of delight during his concerts. For the more accomplished amateurs, Stojowski’s Chant d’amour was available in a variety of editions; by playing the “Song of Love” at home, Paderewski’s admirers could indulge in their fascination.

NOTE: This article contains material from a research paper Dr. Trochimczyk presented at the annual meetings of the American Musicological Society (2002) and Society for American Music (2003), “How Paderewski Plays: Chant d’amour and the Aestheticism of America’s Gilded Age.” In this abridged version of the material, notes to various sources have been omitted.

Awards

Ochlewski Composition Competition

The first place prize in the Tadeusz Ochlewski Composition Competition has been granted for Wariacje na temat pewnego odrodzenia – a composition of Paula Stach. A distinction has been granted for Wołanie o ciszę written by Alina Blonska. The subject of this year’s competition was composition for clarinet solo. The prizes for first place and the distinction will include publication of both works in An Anthology of Contemporary Musicas well as material prizes. Additionally both compositions will be presented during the Warsaw Autumn Festival and “A Theme with Variations”.

The first place prize in the Tadeusz Ochlewski Composition Competition has been granted for Wariacje na temat pewnego odrodzenia – a composition of Paula Stach. A distinction has been granted for Wołanie o ciszę written by Alina Blonska. The subject of this year’s competition was composition for clarinet solo. The prizes for first place and the distinction will include publication of both works in An Anthology of Contemporary Musicas well as material prizes. Additionally both compositions will be presented during the Warsaw Autumn Festival and “A Theme with Variations”.

The subject of the 2004 competition will be a composition for solo classical guitar.

Birthdays & Awards

Górecki & Penderecki, who celebrated their 70th birthdays last year, were also the recipients of the “Małopolanin” [Little Polonian] title for the year 2003 from the society of counties and provinces from Małopolska [Little Poland] in southern Poland. The award was scheduled to be presented during a charity ball at Wawel Castle in Krakow on 21 February.

Upcoming Kosciuszko Competitions

The Sembrich Voice Competition sponsored by the Kosciuszko Foundation of New York will be held at Hunter College on March 13th and the 2004 Chopin Piano Competition will take place on April 1-3. For more information visit www.thekf.org.

Performances

Polish Day At MIDEM

During this year’s edition of the MIDEM International Music Market in Cannes (January 25-29, 2004), Poland was represented by composer Wojciech Kilar and the Polska Orkiestra Radiowa [Polish Radio Orchestra], vocalist Anna Maria Jopek and her group, and graphic artist Roslaw Szaybo. The most important event of “Polish Day” was a gala concert, which featured a performance of Kilar’s newest work entitled September Symphony, inspired by the events of September 11th, 2001 and an award presented to the composer by TV Polonia. Those attending also heard other works by Kilar, including his symphonic poems Orawa and Krzesany, as well as his suite from the film Dracula (dir. Francis Ford Coppola). It was the music to this film that gained the composer an award of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP). The September Symphony was conducted by under American John Axelrod and all other pieces were conducted by Wojciech Rayski. Later in the evening of “Polish Day”, Anna Maria Jopek appeared in concert with her ensemble at the highly exclusive Hotel Carlton. Graphic artist Roslaw Szaybo, who specializes in designing album covers and jazz posters, hosted an exhibition of his musically inspired graphic works at the Festival Palace.

New York Philharmonic Plays Szymanowski

Conductor Kurt Masur and violinist Glenn Dicterow led the New York Philharmonic in a four dazzling performance of Karol Szymanowski’s First Violin Concerto (1916) at the Lincoln Center in January. According to Anthony Tommasini of the New York Times, who described the concerto with lush, sensual words that reveal his appreciation for Szymanowski, “Mr. Dicterow gave a technically assured and luminous performance of the demanding violin part, as Mr. Masur drew glittering playing from the orchestra.”

The full text of this New York Times review by Anthony Tommasini, entitled “Masur and Musicians: A Chance to Reconnect”, can be viewed at nytimes.com.

Skrowaczewski Premiere

A new symphony by Polish composer/conductor Stanisław Skrowaczewski had its premiere in Minnesota at Orchestra Hall on October 2, 2003, a day before the composer’s 80th birthday with the composer conducting the Minnesota orchestra. Michael Anthony gave a lengthy and favorable report on it in the Jan/Feb 2004 issue of American Record Guide.

According to Mr. Anthony, Skrowaczewski started composing at age 7 in his native Poland, and “focused almost exclusively on conducting in later years, as chief conductor of the Warsaw National Orchestra (1956-1959) and during his first decade as music director of the Minnesota Orchestra, a position he held from 1960 to 1979 (he is now conductor laureate). He began conducting again in 1969, when the Philadelphia Orchestra premiered his English Horn Concerto, and he has written a great deal since, both chamber music and orchestral scores. Two of his works have been nominated for the Pulitzer Prize: the Passacaglia Imaginaria in 1997 and the revised version of the Concerto for Orchestra in 1999.”

Skrowaczewski is highly respected for his Bruckner recordings and the critic states that “his Bruckner doesn’t sound like anyone else’s” and he goes on to hearing “something of Bruckner” in the symphony’s “finale, though very much in Skrowaczewski’s own voice.” He ends his report with the words “engrossing performance.” This should make for an interesting recording.

Anderszewski Delights NY

Polish pianist, Piotr Anderszewski, received a ten-minute ovation from the sold-out house (despite the bitter winter weather outside) on January 18th where he performed the music of Bach, Chopin and Szymanowski. Anderszewski, who studied at USC several years ago, is hailed as one of the three greatest Polish artists of today, next to Ewa Podleś and Krystian Zimerman.

Zbigniew Basara quoted New York critics in his article for Nowy Dziennik of 23 January. The New York Sun titled its review, “Play it Again, Peter.” Bernard Holland of the New York Times stated that despite his young age, he belongs to an exclusive group of pianists who can play whatever pleases him and still fill the hall, even on the worst day of the season. Jay Nordlinger of the New York Sun described Anderszewski as, “an unusually intelligent pianist, whose interpretations are deeply thought through.” The recital was part of the Great Performers Series at the prestigious Lincoln Center Alice Tully Hall.

Calendar of Events

FEB 4: Chopin: Cello Sonata. Steven Isserlis, vc., Ana-Maria Vera, piano. Abbotsholme School, Rocester, Eng. 01543 263304.

FEB 6: Same as above. Jacqueline Du Pre Music Building, Oxford, England. 01 865 305305

FEB 6: Wieniawski: Legende. and others. Midori, v. Herbst Theater, San Francisco. 415-398-6449.

FEB 20: Ewa Podleś, contralto. Music of Moniuszko, Szymanowski, Turina and Dvorak. Philadelphia Chamber Music Society. Perelman theatre. Friday, 8:00 p.m.

FEB 23: Ewa Podleś, contralto. Vocal Arts Society. Kennedy Center Terrace Theater, Washington, D.C. 7:30 p.m. $35.

FEB 28: Ewa Podleś, contralto. Michigan Opera Theatre Presents. Detroit Opera House. 8:00 p.m. 313-237-SING.

News Of Our Friends

Laura Grażyna Kafka

Dr. Laura Grażyna Kafka, soprano, is from Monterey, California and is the first person in her family to be born in America. Thanks to her parents passing on their Polish heritage to her, she speaks Polish fluently and specializes in singing Polish vocal music. Dr. Kafka is one of the leading experts on the music and life of Polish composer Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937). The latest book in the PMC’s Polish Music History Series, The Songs of Karol Szymanowski and Hi Contemporaries, includes a chapter by Dr. Kafka entitled “Karol Szymanowski’s Children’s Rhymes: A Performer’s Perspective”. This chapter is very informative and helpful to any singer searching for insight in how to perform Szymanowski’s music from someone with informed experience.

Dr. Kafka holds a Ph.D. in musicology from the University of Maryland at College Park (the focus of her doctoral dissertation was Szymanowski’s Król Roger), a M.A. in music (voice) from the University of Alaska at Fairbanks, and a B.M. in voice and the B.A. in French from Methodist College in North Carolina. She has taught at the University level accross the U.S. She is currently Music Department and Electives Chair at L’École d’Immersion Française à Robert Goddard in Seabrook, Maryland. Dr. Kafka’s most recent teaching achievement is having joined the applied voice faculty at Georgetown University.

The recipient of numerous vocal and academic awards, Dr. Kafka is an International Research and Exchange Board postdoctoral fellow to Poland. She won First Place in the National Association of Teachers of Singing Vocal Competition in North Carolina, and is an American Council for Polish Culture’s Marcella Kochańska Sembrich Vocal Award recipient. Her numerous concert engagements include Carnegie Hall and the Embassy of the Republic of Poland. Visit her website at http://members.aol.com/lgksinger.

Andrew Rafinski

Andrew Rafinski is a retired chemistry professor and avid pianist of Polish descent who lives in Dartmouth, UK. He recently contacted the PMC wishing to use information on our website for his lectures on Chopin. Andrew is a member of a thriving and active U3A (University of the Third Age), which is a completely informal organization in which members share their knowledge and skills. As a part of the music group in this organization, he gives lectures and lecture-recitals. For his first talk, the theme was possible early influences on Chopin’s compositions, concentrating on the Polonaises and the compositions of Michal Oginski. Retired opera singer Susan Gray joined Andrew in a demonstration of this stately music and then got the whole audience to join in the dance, in order to experience the very Polish feeling of glory, dignity and pride. Another talk focused on Chopin’s last year in Poland, his involvement in opera at the conservatorium and the possible effect these may have had on his compositions. “Lost love—lost homeland”. The evening was finished by singing “Lulaj że Jezuniu” led by Ms. Gray and listening to Chopin’s Scherzo, in which the middle section is based on this carol.

Barbara Zakrzewska

“Bruzdowicz in California” was the title of a full page article that appeared in Nowy Dziennik which described the Polish composer’s visit to USC last December. Barbara Zakrzewska, former librarian at the PMC, as well as a composer herself, wrote an excellent, detailed report on the Paderewski lecture-recital and other activities surrounding the three-day residency of Joanna Bruzdowicz. She also brought up the readers up-to-date on the present holdings of the Polish Music Center.

Internet News

“Bogurodzica” On The Web

A polyglot website concerning the first poem composed in Polish, “Bogurodzica” (13th c.), is now available: http://www.staropolska.gimnazjum.com.pl/ang/middleages/rel_poetry/Wolkowski.php3

Kosciuszko Foundation

In honor of the new year, the Kosciuszko Foundation has updated their website. It is in the same location but with a new look. Visit them at www.kosciuszkofoundation.org or www.thekf.org.

Chopin Honored

http://pages.infinit.net/chopinfr/

This French web site was created by Dr Z.W.Wolkowski, P.M. Curie University, member of the Local Committee of the Polish Library in Paris, in honor of the sesquicentennial anniversary of the death of Chopin (1810-1849) and the bicentennial of his birth. The goal of Dr. Wolkowski is to use this website to share that which is beautiful and true about this beloved artist.

Discography

by Wanda Wilk

DUX Partnership

A recent issue of Nowy Dziennik carried a report on the new partnership between the Polish record label DUX and the Polish- American newspaper from New York. Roman Markowicz informed readers that the company was founded in 1992 by two alumni of the Chopin Academy of Music, Malgorzata Polanska and Lech Tolwinski. He noted that the company now has over 200 titles in its catalog and that they concentrate on younger and lesser known talents, like pianists Stanislaw Drzewiecki and Beata Bilinska, violinists Piotr Plawner and Bartlomiej Niziol and singer Urszula Krygier. The author praised the technical engineering aspects of their CDs and program notes prepared by first class musicologists and critis. He highly recommends this label for all music lovers. All Dux recodings will now be available in the Nowy Dziennik bookstore. For more information, visit www.dux.pl.

5 Stars For Rubenstein

BBC Legends BBCL 4130-2

Works by Beethoven, Brahms, Schubert & Chopin. Arthur Rubinstein, p.

In the BBC magazine Dec 2003 issue, Misho Donat gives Arthur Rubinstein’s collection top rating for performance. He states, “Brahms and Chopin were the composers closest to Rubinstein’s heart and his natural sense of rubato served him wonderfully well in both.” He gives it only two stars for sound calling BBc’s monosound on the primitive side, however, “it’s serviceable enough. All in all, a precious document.”

“Il Convegno”

Jan Jakub Bokun and several talented collegues have put out a wonderful new album of jazz from around the world. The title, “Il Convegno”, is inspired by the fourth track by Amilcare Ponchielli (1834-1886). Jan Jakub Bokun is a talented clarinetist and a former USC student.

Paderewski’s Violin Works

DUX 0363

Paderewski: Violin Sonata, Allegro de Concert, Melodia. Konstanty

Kulka, v., Waldemar Malicki, p.

Jan Smaczny of BBC Magazine calls this collection of Paderewski’s violin music a, “real find; only one other recording of the Violin Sonata is available (Pavane) and none of the Allegro de Concert.” The critic does not believe the players are, “well-served by the rather constricted recorded sound.” This comment seems strange in view of the praise that DUX CDs have received elsewhere

Chopin Prediction

VOX VXP 7908

Chopin: Ivan Moravec, p.

Reviewed in Fanfare Jan/Feb ’04 magazine, Michael Ullman concludes his favorable review with, “I fully believe that this will be one of the best Chopin recordings of the year.”

“My Legacy”

ARTEK AR-0011-2

Szymanowski, Chopin, Wieniawski.

Aaron Rosand, violin, Hugh Sung, piano.

Genuine praise from Robert Maxham of Fanfare for Aaron Rosand’s program of music by three Polish composers entitled “My Legacy”. The title refers to the violinist’s heritage, his father was born in Lowicz, Poland and the Chopin Nocturne was his mother’s favorite piece. The critic notes the when this was recorded in May 2001, the “violinist was pushing, even then, towards the middle of the seventh decade of his career.” Nevertheless this has not hindered “his ability to produce all the sound of which his instrument’s capable of.”

Recommended Flute

AVIE 0027

French Flute Music: Dubois, Gaubert, Faure, Tansman, Poulenc, Sancan, Debussy.

Jeffrey Khaner, fl. Hugh Sung, piano.

Immediately, Fanfare‘s music critic Jerry Dubins picks “the odd man out” from among the seven composers. He lets the readers know that Alexandre Tansman (1897-1986) was, “not authentically French, having been born and trained in Poland. He did, however, live in France between the wars, became a French citizen, lived in the U.S. from 1938-46 and returned to France.” He highly recommends this disc primarily because of the flutist, who has been Principal Flute of the Philadelphia Orchestra since 1990.

Angela Lear

This British pianist comes highly recommended from a friend of Polish Music who is also a pianist, and claims that simply listening to her recordings has transformed his own piano technique. He tells us this about Ms. Lear: “She is a Chopin pianist and teacher based in London who has been involved in researching original documents, manuscripts, autograph editions, including annotated scores of Chopin’s pupils, and has discovered that most professional pianists take such liberties in their interpretation of Chopin that they distort the music and don’t play it according to Chopin’s intentions. She has recorded six CDs which I have bought, and I must admit that her playing is the best I have ever heard. She creates the most beautiful bel canto, and her subtle rubato arises from a perfect sense of timing.”

This British pianist comes highly recommended from a friend of Polish Music who is also a pianist, and claims that simply listening to her recordings has transformed his own piano technique. He tells us this about Ms. Lear: “She is a Chopin pianist and teacher based in London who has been involved in researching original documents, manuscripts, autograph editions, including annotated scores of Chopin’s pupils, and has discovered that most professional pianists take such liberties in their interpretation of Chopin that they distort the music and don’t play it according to Chopin’s intentions. She has recorded six CDs which I have bought, and I must admit that her playing is the best I have ever heard. She creates the most beautiful bel canto, and her subtle rubato arises from a perfect sense of timing.”

Ms. Lear has performed all over the U.K. and the world, sharing her knowledge of Chopin and her skill with his music, and has received 5 stars for her performance from the BBC Music Magazine.

For more information and samples of her music, visit Ms. Lear’s website: www.angelalear.co.uk.

A Reminder

Have you bought your Murray Perahia disc of Chopin yet? This recording of Chopin’s Etudes Op. 10 and Op. 25 was the winner of the Gramophone 2003 Best Instrumental Record Award.

Anniversaries

Born This Month

- 2 February 1909 – Grażyna BACEWICZ, composer, violinist, pianist (d. 1969)

- 7 February 1877 – Feliks NOWOWIEJSKI, composer, organist

- 8 February 1953 – Mieszko GÓRSKI, composer, teacher (active in Gdansk and Koszalin)

- 9 February 1954 – Marian GORDIEJUK, composer, teacher, theorist (active in Bydgoszcz)

- 14 February 1882 – Ignacy FRIEDMAN, pianist and composer (d. 1948)

- 18 February 1881 – Zygmunt MOSSOCZY, opera singer (bass), chemist (d. 1962)

- 27 February 1898 – Bronisław RUTKOWSKI, organist, music critic, conductor and composer (d. 1964)

- 28 February 1910 – Roman MACIEJEWSKI, composer, pianist (d. 1998 in Sweden)

- 28 February 1953 – Marcin BŁAŻEWICZ, composer, teacher (active in Warsaw)

Died This Month

- 3 February 1959 – Stanisław GRUSZCZYŃSKI, tenor (active throughout Europe, b. 1891)

- 3 February 1929 – Antoni Wawrzyniec GRUDZIŃSKI, pianist, teacher, and music critic (active in Łódz and Warsaw, b. 1875)

- 7 February 1954 – Jan Adam MAKLAKIEWICZ, composer (active in Warsaw, b. 1899)

- 7 February 1994 – Witold LUTOSŁAWSKI, composer and conductor (b. 1913)

- 9 February 1959 – Ignacy NEUMARK, composer and conductor (active in Copenhagen, Oslo and Schveningen, b. 1888)

- 10 February 1905 – Ignacy KRZYŻANOWSKI, pianist and composer (active in Kraków and Warsaw, b. 1826)

- 14 February 1957 – Wawrzyniec Jerzy ŻUŁAWSKI, composer, music critic, teacher, and mountain climber (b. 1916)

- 23 February 1957 – Stefan SLĄZAK, singer, organist, conductor (active in Silesia, b. 1889)

- 27 February 1831 – Józef KOZŁOWSKI, composer (active at the Russian Court in Petersburg, b. 1757)