Polish Music Reference Center Newsletter Vol. 5, no. 8

News Flash

Sikora Wins Prix Magistere at Bourges!

Polish composer living in France Elzbieta Sikora won the Prix Magistere for her work “Aquamarina” at the 1999 Electroacoustic Musical Competition in Bourges, France. The competition included submissions from 508 composers from 40 countries and the prize is a special award for the most distinguished composers active in the electroacoustic field. A CD of this prize-winning work will be released and performed on more than 30 radio stations throughout the world.This was the 26th edition of the competition and judges included Françoise Barrierre, Gerald Bennet, Luigi Ceccarelli, Francis Dhomont, Sten Hanson, Anne Roquiny, Joran Rudi, and Jean-Philippe Vienne – composers, educators and administrators active in the electroacoustic music field. The competition awards prizes in different categories – for electroacoustic music with and without instruments, for music on the Internet or CDROM, for music that accompanies theatre spectacles and dance, for installation and improvisation with new computer devices. There are only two prizes higher than the Prix Magistere received by Sikora – the Grand Prix (silver and gold). For more information about this competition visit the web site of the Institut International de Musique Electroacoustique de Bourges / IMEB that organizes and manages these competitions. The address: www.gmeb.fr

Wanda Wilk’s article on Polish women composers, included in the “essays” section of the PMRC web site includes the following biographical notes about the prize-winning composer. Elzbieta Sikora (b.1944) studied sound recording at the F. Chopin Music Academy in Warsaw, before shifting to composition. After graduation (1968) she received a French Government scholarship and moved to Paris to work on electroacoustic music at the now famous Groupe de Recherches Musicales. She made her debut as a composer in 1971, while she was still a student of composition under Tadeusz Baird and Zbigniew Rudzinski; this debut compositon Intervention, is a musical parable for two percussionists, baritone tuba, and symphony orchestra on tape.

Sikora received numerous prizes, among others at the Composers Competition in Dresden for her opera Ariadna1977), at the Experimental Music Competition in Bourges for Waste Land (1982), and Letters to M.(1980), at Young Composers Competition in Warsaw for …according to Pascal (1976)and at the Women Composers Competition in Mannheim for Guernica ( 1975-1979). Her most recent commission was a cantata celebrating the millennium of her native city of Gdansk. At present she is a professor of electronic music at the Music Conservatory in Angouleme.

This information should be complemented with two recent news items: she was commissioned to write a piece to celebrate the 1000 anniversary of her home city of Gdansk and composed a monumental work for the 1999 visit of Pope John Paul II to Poland.

News

Complete Recordings Of Artur Rubinstein

BMG Classics will be releasing The Arthur Rubinstein Collection, a 94-CD set containing this seminal pianist’s entire recording history, some of which are:

- Documentation of Performance Practice; Rubinstein was one of the pivotal pianists of the 20th century, with his life spanning from 1887 through 1982. This collection will be central to the teaching and scholarly examination of the development of piano performance, the piano repertoire and Rubinstein’s own musical idiom. These trends are most revealingly documented by several instances of multiple recordings, which include:

- Three Chopin cycles, dating from the early 1930s, the early 1950s, and the early 1960s;

- Three complete Beethoven Concerto cycles, dating from the late 1950s, the mid-1960s, and 1976, the last among his final recordings;

- Multiple versions of many other pieces from the standard piano repertoire, including the Schumann and Grieg piano concertos, and much of the solo repertoire by Brahms and Schumann.

- New Primary Sources; In addition to the invaluable primary-source material of the musical recordings themselves, this collection has an accompanying book, which provides entirely new documentary commentary by Daniel Barenboim, Zubin Mehta, Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, Arnold Steinhardt of the Guarneri Quartet, Donald Manildi, and the pianist’s younger son, actor and composer John Rubinstein.

- Wide-Ranging Repertoire; This collection provides access to a vast majority of the piano repertoire, which includes, in addition to all the standard works, music by Alb niz, Debussy, Falla, Poulenc, Prokofiev, Rachmaninoff, Ravel, Saint-Sa ns, Szymanowski and Villa-Lobos. As an early exponent of their works, Rubinstein played an important role in their acceptance into the canon.

- Documentation of Brahms’ & Schumann’s Piano Traditions; Rubinstein’s interpretive tradition can be traced directly back to Brahms via his mentor in Berlin, the violinist Joseph Joachim, and ultimately to Schumann via Brahms.

- Documentation of Recording History; In its comprehensive representation of Rubinstein’s entire recording history, which spanned from 1928 through 1976, this collection presents insights into the history of recorded music. The set includes all studio recordings made by Rubinstein, as well as two complete live recitals.

- In addition, a 2-CD bonus volume introduces three compositions new to the Rubinstein discography: Debussy’s Mouvement from Images, Book I (rec. 1945); Chopin’s Prelude, Opus 45 (rec. 1957); and Schumann’s Novellette, Opus 21, No. 5 (rec. 1953); plus a never-before released recording of Albeniz’ Evocacion (rec. 1949). The bonus volume also includes two interviews with the artist.

This special collection will be released in a limited numbered edition only. For more information visit the Rubinstein Collection site at:Rubinstein Collection.

World War II – 60th Anniversary Concert, Warsaw

The Cantores Minores Choir of the St. John the Baptist Cathedral in Warsaw, led by Joseph Herter, currently prepare a a special concert, scheduled for 1 September 1999 and entitled Da pacem, Domine to mark the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of World War II. The concert will take place at the Chopin Academy of Music, under the honorary patronage of Mr. Janusz Onyszkiewicz, the Polish Minister of National Defense, and Mr. Paweł Piskorski, the Mayor of Warsaw. The former has agreed to address the audience at the concert.In addition to the Warsaw choir there will also be the Berlin Knabenchor (Larl-Ludwig Hecht, conductor) the Szczecin Nightingales (Bozena Derwich, conductor), The Indonesian Children’s Choir from Jakarta (Ida Swenson, conductor), and the Bialystok Medical Choir (Bozena Sawicka, conductor). The soloists include: Gregory Moore – baritone (USA), Franciszek Miklaszewicz – boy soprano, Anna Maćkowiak – soprano, Franciszek Kubicki – contratenor, Adam Wlazly – tenor.

The program consists of the following works:

- Procession for Peace – Andrzej Panufnik

- Dona nobis pacem from “Mass in B Minor” – J.S. Bach

- Libera me, Domine from “Requiem” – Gabriel Faure

- Polonia – Edward Elgar

- Chichester Psalms – Leonard Bernstein

Mr. Herter is now busily fundraising to cover cost of housing and feeding these choirs, renting the hall and hiring the “ad hoc” orchestra of members from the Warsaw Philharmonic and Sinfonia Varsovia. If anyone here would like to offer help please e-mail him: Mr. Herter.

The Bacewicz Year and PWM

Grażyna Bacewicz’s double anniversary celebration this year (her 90th of birth and 30th of death) has been filled with events, from the Bacewicz Days held at the Polish Radio in January (see our February newsletter) to the special monographic concert organized by the PWM Edition Bacewicz’s publishers, for the opening of the Warsaw Autumn Festival in September (see Newsletter). PWM issued special catalogs, posters, programs and the first issue of a new quarterly promotional magazine – all devoted to Bacewicz.

The promotional newsletter is entitled “Quarta” and the first issue appeared in May 1999. It includes numerous bits of information about Bacewicz and her anniversary events in Poland. Among the quoted artists and scholars who admired her work are composer Witold Lutoslawski and pianist Krystian Zimerman. The latter states: “I am very much fascinated by both of the piano quintets by Grażyna Bacewicz, which in my opinion are amongst the best works of this composer and, as far as the chamber music repertoire is concerned, are indeed works ofo world stature.”

To obtain a copy and subscribe to this newsletter contact the Promotional Department of PWM Edition, al. Krasinskiego 11a, 31-111 Krakow, Poland, e-mail: promotion@pwm.com.pl. You may also visit their web site at:www.pwm.com.pl.

Bacewicz And A New Book On Women Composers

The Scarecrow Press has just published a book on women in music entitled: “Women Composers, Conductors, and Musicians of the Twentieth Century.” Vol. III. Author Jane Weiner Le Page includes the outstanding Polish composer Grażyna Bacewicz among these selected biographies. We should add that Bacewicz is often listed in such publications, but by herself is the subject of four books: two published by PMRC (by Rosen and Thomas), one by PWM (by Gasiorowska, in Polish), and one by Mellen Press (by Shafer, on Bacewicz’s songs).

The Chopin Year

Chopin’s Letters And UNESCO

The Newsletter of the Embassy of the Republic of Poland in Washington, D.C., reports in its June-July issue that Chopin’s letters and autographs of his compositions held at the Chopin Society in Warsaw have been added to the “Memory of the World List” maintained by UNESCO. The list names and locates the most precious cultural and historical documents of human civilization. Two other Polish documents have also been added to the list in June: the authograph of the Nicolaus Copernicus “De revolutionibus libris sex” at the Jagiellonian Library in Krakow, and the archives of the Warsaw ghetto which include documents on the fate of Jews in the Nazi-occupied Poland.

The Newsletter of the Embassy of the Republic of Poland in Washington, D.C., reports in its June-July issue that Chopin’s letters and autographs of his compositions held at the Chopin Society in Warsaw have been added to the “Memory of the World List” maintained by UNESCO. The list names and locates the most precious cultural and historical documents of human civilization. Two other Polish documents have also been added to the list in June: the authograph of the Nicolaus Copernicus “De revolutionibus libris sex” at the Jagiellonian Library in Krakow, and the archives of the Warsaw ghetto which include documents on the fate of Jews in the Nazi-occupied Poland.

“Chopin” – International Piano Symposium In California

Masterclasses International has scheduled an International Piano Symposium dedicated to Chopin for August 1-8, 1999 at the Pepperdine University Campus in Malibu, California. The Moscow Conservatory and world-renowned pianists from Poland and the U.S. will be featured (as listed in July Newsletter). Prof. Halina Czerny-Stefanska, first prize winner at the Chopin Competition of 1949 will perform on Saturday, August 7, at 8:30 p.m. She will also appear in a concert of all participating artist faculty on Sunday, August 1, at 5:00 p.m.

For more information contact Smothers Theatre, Center for the Arts, Pepperdine University, 24255 Pacific Coast Highway, Malibu, California. tel. 310-456-4522. Alternatively, you may contact Master Classes International at 213-383-3524.

Chopin Festival In Antonin

Professor Regina Smendzianka will be the first to perform at the new Steinway piano (donated to the Radziwill Hunting Palace in Antonin, Poland) during the International Chopin Festival in September. The donation was made by Wincenty Broniwoj-Orlinski of Hamburg, who had been born in Poland, but who spent most of his years abroad after being released from a German prison in World War II. He had previously presented a new organ to the Cathedral in Poznan (1966) and two years ago the city of Gdansk also received a Steinway piano.

Miami Chopin Competition Deadline

Just a reminder: 30 November is the deadline to submit your application to the Sixth Annual National Chopin Piano Competition in Miami, Florida which will take place 4-12 March 2000. Top prize winners to represent the United States will receive all expenses paid, including airfare, to the International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw, Poland in October, 2000.

The first prize winner will have a Debut Recital at Lincoln Center, a Concert Recital at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. and a concert tour. For an application, required repertoire and other information click onto their website: www.chopin.org.

Chopin Tour To Poland

The Kosciuszko Foundation is sponsoring the Chopin Anniversary Tour to Poland and Paris: October 15-26, 1999. Exclusive recitals, private tours of rare collections and deluxe accomodations for an all inclusive cost from New York is $2,250.

Internet News

Skok – Polish Internet CD Store

The number of internet resources for Polish recordings is growing rapidly. A new online store, named “Skok” (which means “jump” in Polish) presents the most comprehensive catalogue of Polish music on CDs on the Internet. More than 2600 Polish titles are included in their Polish CD catalogue and the catalogue is constantly growing. As the only one store on the net SKOK also includes discontinued editions of CDs to keep Polish music lovers well informed – a good source of information for CD collectors.

The direct link to Polish Music Catalogue is: http://www.alphainter.net/~skok/polishim.html.

The address for the main page is: http://www.alphainter.net/skok

E-mail address: skok@alphainter.net

Telephone: (613) 741 0613

Fax: (613) 741 5954

Recent Performances

Chopin Festival In Duszniki

Artists at the 54th International Chopin Festival in Duszniki-Zdroj (the Polish resort visited by Chopin in his youth) included, among others, Krzysztof Jablonski, Kevin Kenner, Ching-Yun Hu and Grigrij Sokolov. There were 16 piano recitals, one vocal, one cello and one jazz recital.

Landowska Documentary

“Landowska: Uncommon Visionary,” a documentary on the late Polish harpsichordist, Wanda Landowska (1879-1959), was aired on public television KCET in Los Angeles on 8 July. Chris Pasles wrote a favorable review for the LA Times describing it as “an affectionate and fascinating look at the woman who changed music history, almost single-handedly, by bringing the harpsichord out of the museum and onto the concert stage.

Maestrini – A New Duo in L.A.

Polish violist, Piotr Jandula and Janet Kocyan – pianist and wife of Wojciech Kocyan, have started to concertize together, giving recitals of chamber music. Their apperance on Rancho Palos Verdes, with a program of Bach, Mozart, Rachmaninov, and Franck (June 19, 1999) attracted a large audience, though no music reviewers (there are simply too many music events in L.A. daily). Hopefully, future concerts will also include some Polish music, though Ms. Kocyan’s link to Poland is solely marital.In addition to frequent concertizing, Mr. and Ms. Kocyan are also active in Polish community. They have recently hosted the Choir from the Wroclaw Polytechnical University; the choral concert took place at their San Pedro residence, overlooking the Pacific Ocean (July 13, 1999). The concert included Polish religious music, chants from the Orthodox church, Italian and Spanish folk arrangements, and American spirituals.

The 31st Annual International Polka Festival Convention was held between 29 July and 1 August at the Westin Hotel O’Hare in Rosemont, Illinois.

Calendar Of Events

AUG 1: Chopin Cycle. Gustavo Romero, piano. Athenaeum Music & Arts Library. 10008 Wall St., La Jolla.

AUG 3: Chopin. Natalia Troull, piano. Int’l Piano Symposium @ Pepperdine U., Malibu, California. 8:30 p.m. $20. 213- 383-3524; 310-456-4522.

AUG 5: Chopin Cycle. Conclusion of Chopin’s music by Gustavo Romero.

AUG 5: Chopin. Mikhail Voskressensky, p. Int’l Piano Symposium @ Pepperdine U., Malibu. 8:30 p.m. $20.

AUG 7: Chopin. Halina Czerny-Stefanska, p. Int’l Piano Symposium @ Pepperdine U., Malibu. 8:30 p.m. $20.

AUG 8: Int’l Piano Symposium Closing Concert by participating students. Pepperdine U., Malibu. 3:00 p.m. $20.

AUG 19: “Spirit of Summer.” Chopin Singing Society. Cathedral Green, St. Joseph’s Cathedral, Buffalo, NY. 716- 854-5855.

AUG 29: Dinner & Ball celebrating the 100th Anniversary of the Chopin Singing Society. Statler Tower, Buffalo, NY. 5:00 p.m.

Discography

by Wanda Wilk

Chopin Releases

The latest Schwann catalog lists 44 new releases of Chopin’s music. Among the artists are familiar names from the past as well as not so familiar ones:A. R. El Bacha, W. Bachaus, M. Bloch, John Browning, Albert Cortot, Shura Cherkassky, G. Cziffra, Ignaz Friedman, S. Francois, L. Favre-Kahn, E. Gabriel, H. Gekic, Leopold Godowsky, S. Gorodnitzki, V. Horowitz, William Kapell, Peter Katin, Evgeni Kissin, S. Kovacevich, Dinu Lipatti, Moisevitch, Malcuzynski, G. Montero, G. Novaes, C. Ortiz, Paderewski, M. Pletnev, Rachmaninoff, Richter, Rubinstein, S. Rodriguez, A. Schub, A. Serdar, K. Skanavi, and Adam Walacinski.

Philips – Great Pianists

Two more releases in the Philips Great Pianists of the 20th Century Series:

456 997-2PM2 (2 discs). Krystian Zimerman. Music of Brahms, Debussy and Chopin. Ballade no. 4 & Fantaisie in F Minor. Vienna Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein & Boston Symphony with Seiji Ozawa.

456781-2PM2 (2 discs). Nelson Freire. Music of Brahms, Chopin, Godowsky, Liszt, Schumann and R. Strauss. Munich Philharmonic, Rudolf Kempe, conductor.

Other New Releases

Nimbus Records N11750 of 4 CDs contains Szymanowski’s Complete Piano Music as performed by pianist Martin Jones.

NAXOS 8 554283. LUTOSLAWSKI, vol. 6. Music critics in the Gramophone had nothing but praise for Polish soprano Olga Pasiecznik for her rendition of Chantefleurs et Chantefables, as well as the rest of the recording, vol. 6 of the Lutoslawski Series by Naxos. Polish National Radio Symphony Orch. conducted by Antoni Wit.

Gramophone also reported on the “continued excellence of the budget-price Ultima series. The latest batch includes a highly distinctive set of Chopin Nocturnes, where Ivan Moravec displays rare temperament, imagination and a winning variety of rubato.”

Polish American Bookstore

Interesting CDs are now available from the Polish American Bookstore in New York (10% discount to Kosciuszko Foundation members. Tel: 212-594- 2386. E-mail: ksiazki@dziennik.com).

12 Mazurkas for voice and piano. Agata Winska, sop.; Jozef Sterczynski, piano.

Songs by Chopin, Karlowicz and Moniuszko. Stefania Toczyska, mezzo-soprano, Janusz Olejniczak, piano.

Music of Chopin and Moniuszko for piano duet or two pianos. Krystyna Makowska and Anna Wesolowska, piano.

A Polish Fantasy. Mazur from the opera, “Haunted Manor’ by Moniuszko, Polonaise and other Polish songs performed by the Concert Orchestra of the Polish Army.

History: Edward Elgar’s Polonia

A Polish Overture by a British Composer: “Polonia”, Op. 76 by Edward Elgar

by Joseph Herter

The Great War (1914-18) did not inspire many Polish composers to write music “for the cause.” If one recalls the political situation and borders of a non-existent Poland of that time, the explanation for this is simple. At the outbreak of the First World War, Poland had not existed as a sovereign nation for over a century. It had been partitioned by three of its neighbors and placed under their jurisdiction; these were the Austro-Hungarian, Prussian and Russian Empires. A public performance of a Polish patriotic composition in the partitioned lands would have been illegal and, for all practical purposes, impossible to organize. Turning the divided Polish nation into a battlefield also created a moral dilemma for the Poles who were forced to fight in the armies of their imperial rulers: that of having to go into battle and kill fellow Poles. At the war’s outset, 725,000 Poles in the Russian, 571,000 in the Austrian, and 250,000 in the Prussian partitions were drafted into those countries’ armies.[1] Even though each of the powers promised the Poles some form of autonomy after the “victory” if they would fight for their side during the war[2], writing music for their cause would have been promoting Polish fratricide as well. Moral support for the Polish cause through music would have to come from abroad.

A Pole who responded to the tragic situation into which Poland had been forced was the pianist and composer Zygmunt Stojowski (1870-1946). A student of Leo Delibes – and for shorter periods of time with Dubois, Massenet and Paderewski – Stojowski spent the last 40 years of his life teaching and composing in New York. There in 1915, free from the retaliation of Poland’s occupying powers, Stojowski took a political stance and wrote a cantata for solo voices, mixed chorus and orchestra, “Prayer for Poland” (Modlitwa za Polskę ), op. 40.

Stojowski’s cantata, although long unperformed and forgotten, is one of the few works from the “war to end all wars” which was written on a spiritual base rather than on a totally patriotic one. The poem by Zygmunt Krasiński (1812-59) on which the cantata is based is addressed to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Using the appellation “Queen of Poland” – a title which for centuries the Vatican has allowed Poles to use in the recitation of the Litany of Loreto – the poet calls upon Mary to “End thou for bleeding Poland her deep anguish.”

[Image on the left, above: “Polonia” 1918 by the Polish artist Jacek Malczewski (1854-1929). From a cycle of paintings entitled “Polonia” which were painted during WW I. This one depicts Poland with her crown restored and robed with a legionnaire’s coat. Behind “Polonia” are the unshackled feet of a Pole climbing a set of stairs. Not seen – resting by the Queen’s feet – is her scepter whose head bears a striking resemblance to Józef Piłsudski, the man who became Poland’s leading statesman between the two world wars. From the collection of the Świętokrzyskie Museum, Kielce.]

In writing about music as a voice of war in his book on 20th century music, the noted American musicologist Glenn Watkins states:[3]

At various junctures throughout the twentieth century, man’s search for spiritual values has surfaced in opera, symphony, and Mass; mystery play, ballet and cantata. Yet the period before the beginning of World War I to the conclusion of hostilities was not noticeable for a musical corpus with a pronounced spiritual base, and while the anxiety of a society on the eve of global conflict has frequently been seen as the root of the Expressionist movement, the number of musical statements that speak directly of the war of 1914-18 are few.

Ignacy Paderewski (1860-1941) responded to the cause of Polish independence by writing his only choral work, “Hej, Orle biały” (Hey, White Eagle), for male chorus and piano or military band in 1917. This was the official hymn of the Polish Army in America, for whose creation Paderewski was largely responsible.

Ignacy Paderewski (1860-1941) responded to the cause of Polish independence by writing his only choral work, “Hej, Orle biały” (Hey, White Eagle), for male chorus and piano or military band in 1917. This was the official hymn of the Polish Army in America, for whose creation Paderewski was largely responsible.

The Polish Army in America consisted of over 20,000 enlisted Polish immigrants living in the United States, but who were not American citizens. This army trained in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, and later joined the Polish Army in France, which brought their number to over 35,000.[4]

[Image on the left: The cover of Paderewski’s hymn which was dedicated to the Polish Army in America and published in New York. Depicted on the cover is a Polish uhlan riding into battle. From the collection of the National Library (Biblioteka Narodowa), Warsaw, used by permission].

As the war came to an end, Feliks Nowowiejski (1877-1946) wrote an organ prelude entitled Friede, schönstes Glück der Erde, op. 31 nr. 5, which was based on the Schubert lied of the same title. A former student of Bruch and Dvořak, and a well-known organist and composer throughout Europe, Nowowiejski was named an honorary member of The Organ Society of London in 1931.

It was with Edward Elgar’s fantasia on Polish national airs, though, that the most outstanding, dramatic and nobly patriotic musical gesture for the Polish cause came into being during the First World War. Elgar, however, was not the first composer to have written a work entitled “Polonia”. The young Richard Wagner (1813-83), at one time sympathetic to Poland’s fate, wrote an overture bearing the same title in 1836. In 1883, Franz Liszt (1811-86) also wrote a work entitled “Salve, Polonia”, an orchestral interlude from his uncompleted oratorio “The Legend of St. Stanislaus”. All three compositions by Elgar, Wagner and Liszt make use of The Dąbrowski Mazurka, the hymn which was to become Poland’s national anthem after it regained its independence. The title of Elgar’s work, though, may not have come from the earlier works of Wagner and Liszt, but rather from compositions of the two Polish musicians most closely associated with the creation of Elgar’s piece: Paderewski and Emil Młynarski.

Paderewski, to whom Elgar’s Polish fantasia is dedicated, wrote his Symphony in B minor, op. 24 and gave it the name “Polonia” as well. The symphony – Paderewski’s only work in this genre – was inspired by the 40th anniversary of the 1863-64 Polish Uprising and completed in 1909. The symphony was premiered in Boston on January 12, 1909, with the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Max Fiedler. Paderewski uses the Polish National Anthem as well in this work. Unlike Elgar, however, who uses the hymn in its entirety, or Wagner and Liszt who write variations on the melody, Paderewski uses a motif from the hymn in the symphony’s last movement Vivace. The motif is discretely employed, one might even say – cleverly hidden – as a “hope leitmotif” for the rebirth of Poland. Even listeners who are familiar with the opening phrase of the Polish hymn and its text “Jeszcze Polska nie zginęla, kiedy my żyjemy” (Poland has not yet been lost so long as we still shall live) might easily let Paderewski’s use of the motif pass without recognizing it.

Emil Młynarski (1870-1935), who was responsible for asking Elgar to make his noble statement in support of the Polish cause in April 1915, completed his Symphony in F major, op. 14 in 1910. The composer did not give the title “Polonia” to his only symphony; rather it was a nickname given to the piece by other Polish musicians. The nickname is still often listed as part of the official title in catalogues of the composer’s works. According to Tadeusz Sygietyński (1896-1955), a composer and the founder of the internationally renowned Polish Song and Dance Ensemble Mazowsze, Młynarski’s symphony should bear this name because of its relationship in tragedy to Polish history as depicted in the cycle of paintings entitled “Polonia” by the 19th century Polish artist Artur Grottger.[5]

Młynarski, unlike any of the other composers whose works bear the same title, does not use “Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła” in his composition.

[Image on the left: Emil Młynarski, the Polish conductor and composer, who asked Elgar to compose “Polonia” in aid of the Polish Victims Relief Fund. From the archives of the National Opera (Teatr Wielki), Warsaw, used by permission.]

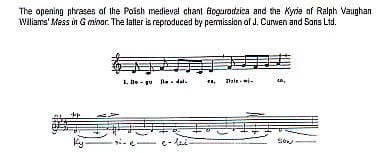

Instead, he uses Polish dances – a mazurka in the third and a krakowiak in the fourth movements – and also employs the 13th century hymn to the Blessed Virgin Mary “Bogurodzica” (Mother of God) which is still well known and sung by Poles today. This hymn, which has the distinction of being the oldest recorded Polish melody and poetry in existence, was sung by Polish warriors as they went into battle against the Teutonic Knights. The first seven notes of the medieval Bogurodzica are the exact same seven pitches of the opening theme of the “Kyrie in Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Mass in G minor” of 1922 (see example 1 below). The premiere of Młynarski’s “Polonia” took place on February 6, 1911, in Glasgow with the Scottish Symphony Orchestra performing and the composer at the orchestra’s helm.

In addition to being a composer, Młynarski was also a famous conductor and it is for his role in this profession that he is best remembered today. He was the first conductor of the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra (1901-05). In the first decade of the 20th century he guest conducted in Russia and in the British cities of London, Glasgow, Liverpool and Manchester. From 1910-15 he was the music director of the Scottish Symphony Orchestra in Glasgow. His association with Elgar also included collaborating with him and Thomas Beecham in presenting a three-day festival of British music in 1915.[6] It would also be Młynarski who would conduct the first Polish performance of “Polonia” at the Philharmonic Hall in Warsaw during the final days of the war on October 4, 1918.[7] Following the war, Młynarski’s responsibilities included the directorship of both the Opera House (Teatr Wielki) and the Music Conservatory in Warsaw. After the war his guest conducting took him to the capitals of Europe and to major cities in America, where he joined the faculty of the Curtis School of Music in Philadelphia in 1929.

Elgar would not be the last famous composer to write a work entitled “Polonia”.[8] In fact, it was Elgar’s composition which became a source of consolation and inspiration for one of Poland’s greatest composers and conductors of the second half of the 20th century – Andrzej Panufnik (1914-1990). In search of political and artistic freedom, Panufnik escaped to the West and settled in England in 1954. As a conductor and Musical Director of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra,he was responsible for a revival of Elgar’s work during the 1957-58 season. Also showing Panufnik’s affinity for “Polonia” is a 1997 BBC Radio Classics recording with Sir Andrzej conducting it in a 1978 performance with the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra. As a composer,though, Panufnik gave credit to Elgar for his own 1959 orchestral work of the same title. In his autobiography Panufnik writes:[9]

It was not easy to start those spirited dances at a time of great loneliness… For a while I couldIcould not start. But then I started to think about Elgar’s sombre and noble “Polonia”, a work most evocatively echoing the heroic and tragic elements of Polish history. I decided to use the same title but to adopt a completely different approach, so that the two works together might provide a full spectrum of the Polish spirit and colour. Elgar made use of Polish patriotic songs but also took some of Chopin’s melodies, ending powerfully with the Polish National Anthem. In contrast I based my new-born “Polonia” on folk melodies and the vigorous, full-blooded rhythms of peasant dances.

Elgar’s compassion for the Poles’ tragic suffering during the war served as an example for other English composers to make their own Polish musical statements in kind. Arnold Bax (1883-1953) saw a similar need to help the Poles during World War Two (1939-45). Bax’s response was “Five Fantasies on Polish Christmas Carols” which were dedicated “To the Children of Poland” and scored for unison chorus and string orchestra. As Jan Sliwiński writes in the preface of the piano-vocal score of the Bax carols, the composer’s arrangements were “…meant to turn the blood of war into the balm of love. British children were to have sung them in aid of their starving Polish brothers and sisters.” Another British composer, Benjamin Britten (1913-1976), also moved by the plight which Polish children experienced during WW II, took up the same theme in his choral work “The Children’s Crusade, op. 82”. Scored for children’s voices, percussion, two pianos and electronic organ, this ballad is a setting in English of Bertolt Brecht’s Kinderkreuzzug. It begins, “In Poland, in 1939, there was the bloodiest fight.” The world premiere of Britten’s work took place in 1969 on the 50th anniversary of Save the Children Fund, a British charity which was founded by Eglantyne Jebb to save starving Austrian children who were victims of a blockade imposed after the First World War.

“Polonia” was expressly written for the purpose of being performed at benefit concerts in aid of the Polish Victims Relief Fund, the raising of money for which was the primary activity of the Polish Victims Relief Committee. The Committee, which eventually established chapters in France, Great Britain, Switzerland and the United States, was founded in Vevey, Switzerland, in January 1915 by a group of eminent Poles who had planned the Committee’s formation with Paderewski at his Swiss villa in Riond-Bosson. Jointly heading the Committee were Paderewski and Henryk Sienkiewicz (1846-1916), the author of “Quo vadis?” and, in 1905, the first Polish laureate of the Nobel Prize for Literature. While calling upon others to assist hundreds of thousands of Poles, who were in desperate need of food, clothing and shelter, Paderewski, himself, donated more than $2 million from his own personal fortune to help his fellow countrymen.[10]

Paderewski sought the most influential people in each country to either organize, lead or join the four national chapters of the Committee. In the United States, it was former President William Howard Taft (1857-1930) who headed the American Committee. In France, Paderewski succeeded in obtaining the help of former French President Emile Loubet (1838-1929) to organize the Committee there. Great Britain was no exception. The British Committee consisted of a star-studded list of artists and high ranking members of British society and government circles. Included with Elgar and his wife Alice were the famous English writers Thomas Hardy[11] and Rudyard Kipling. (Unfortunately, the Polish-born English novelist Joseph Conrad refused to join Paderewski’s efforts because of a disagreement about the way the French Committee had been organized). Other notable persons included the following: Arthur James Balfour, the Marquess of Crewe, the Duke and Duchess of Norfolk, the Duke and Duchess of Somerset, the Duchess of Bedford, the Marquis and Marchioness of Ripon, the Earl of Roseberry, former Prime Minister Lord Burnham, Prime Minister Asquith, future Prime Minister Lloyd George, Reginald McKenna, Winston Churchill, Austen Chamberlain, Lord Northcliffe, Lord Charles Beresford and Viscount Edward Grey.[12]

Paderewski sought the most influential people in each country to either organize, lead or join the four national chapters of the Committee. In the United States, it was former President William Howard Taft (1857-1930) who headed the American Committee. In France, Paderewski succeeded in obtaining the help of former French President Emile Loubet (1838-1929) to organize the Committee there. Great Britain was no exception. The British Committee consisted of a star-studded list of artists and high ranking members of British society and government circles. Included with Elgar and his wife Alice were the famous English writers Thomas Hardy[11] and Rudyard Kipling. (Unfortunately, the Polish-born English novelist Joseph Conrad refused to join Paderewski’s efforts because of a disagreement about the way the French Committee had been organized). Other notable persons included the following: Arthur James Balfour, the Marquess of Crewe, the Duke and Duchess of Norfolk, the Duke and Duchess of Somerset, the Duchess of Bedford, the Marquis and Marchioness of Ripon, the Earl of Roseberry, former Prime Minister Lord Burnham, Prime Minister Asquith, future Prime Minister Lloyd George, Reginald McKenna, Winston Churchill, Austen Chamberlain, Lord Northcliffe, Lord Charles Beresford and Viscount Edward Grey.[12]

In the first several months of its existence, the British Committee’s Polish Victims Relief Fund raised more than 50 thousand pounds sterling.[13]

The world premiere of Elgar’s “Polonia” took place on July 6, 1915, with Sir Edward conducting the London Symphony Orchestra at Queen’s Hall in London in a benefit concert for the Polish Victims Relief Fund. Other works on the concert included one movement from Młynarski’s “Polonia” Symphony and Paderewski’s “Polish Fantasy on Original Themes for Piano and Orchestra, op. 19.14”

The thematic material for Elgar’s composition is drawn from both traditional Polish tunes and from compositions by Frederic Chopin and Paderewski. The former include “Śmiało podnieśmy sztandar nasz w górę” (Bravely Let Us Lift up Our Flag) also known as the “1905 Warszawianka” by Józef Pławiński, “Z dymem pożarów” (With the Smoke of Fires) also known as Chorale by Józef Nikorowicz (1827-1890) and “The Dąbrowski Mazurka” which has been the Poles’ national hymn since the regaining of Polish independence. The latter group includes the opening theme from Paderewski’s Polish Fantasy for Piano and Orchestra, op. 19 and a quotation from Chopin’s Nocturne no. 11 in G minor, op. 37 no.1.

In the introduction to the full score of “Polonia” Jerrold Northrop Moore states that it was Młynarski who proposed the Polish national melodies to be used, but that it was Elgar who selected the quotations from Chopin and Paderewski. These national melodies will surely be unfamiliar to the non-Polish listener. The “1905 Warszawianka” is the first song used in the introduction of the fantasia. It is the two-measure dotted-rhythm melody which is first heard in measure no. 4 as played by the bassoons and bass clarinet. Later, it is not only used as a transitional motif between sections of the fantasia, but the motif is also developed in two separate sections of the composition which give a unifying force to the work. Although the text of the song itself dates from the 19th century and was written by WacŁaw Święcicki (1848-1900), it became popular when sung to a melody by Józef Pławiński and was used as an uprising song against the Russians in Warsaw in 1905. This song became popular with workers’ movements throughout Europe. It was translated into over a dozen languages and accompanied the revolutionary communist movement in many European countries.[15] The following hymn and the other Polish national hymns given below in English have been translated by the author.

Bravely let us lift up our flag,

Even though the storm of the unrestrained enemy rages,

Even though their unbearable force treads us down,

Even if it is uncertain to whom tomorrow belongs.

Onward, Warsaw!

Onward to the bloody fight, which is holy and just!

March on, Warsaw, march on!“The 1905 Warszawianka” (used by permission of Grupa Wydawnicza “Słowo”.)

The second national tune “With the Smoke of Fire” or “Chorale” came into being following the Austrian Army’s bloody suppression of the Cracow Uprising of 1846. As a national song, it best conveys the patriotic agony which the Polish nation experienced during the 123-year-long period of partitions by the Russian, Prussian and Austro-Hungarian Empires.[16] Sung at both patriotic manifestations and at church services, the occupying powers soon forbade the public singing of this hymn. Punishment for performing the hymn was severest in the Prussian territories.

Elgar uses this melody twice in its entirety in his symphonic prelude. The first time is after Elgar’s “nobilmente” original thematic material, which immediately follows the introduction, and the second time is just prior to the finale containing what is now known as the Polish National Anthem – “The Dąbrowski Mazurka”. Almost 30 years later, this hymn would be used once again to give the Poles courage when Radio London signaled the partisans in the nation’s capital to begin the Warsaw Uprising of August 1944.[17] The Chorale written by Nikorowicz was sung to the tragic text of Kornel Ujejski (1823-1897).

Our voices ring out to You, O Lord,

With the smoke of fires and the dust of fraternal blood.

The complaint is frightful; it is our last moan.

From these prayers our hair turns gray.

By now the complaints have stopped

And the songs we know are none.

Forever a crown of thorns has grown into our forehead

As a monument to your anger.

To You we outstretch our imploring hands.[“Chorale,” used by permission of Grupa Wydawnicza “Słowo”.)

The last national tune used by Elgar is the Polish National Anthem which forms the basis of the fantasia’s triumphant finale. The anthem’s alternative title, “The Dąbrowski Mazurka”, refers to General Jan Henryk Dąbrowski, the leader of the Polish Legions who fought for Napoleon Bonaparte. The hymn dates from 1797 and was written in Reggio Emilia, Italy, by Józef Wybicki (1747-1822). The tune given to the hymn was a popular Polish folk melody. As it was sung by the legionnaires in their battles and journeys, the melody stayed with the Slavs in what is known as Yugoslavia and became the tune of their national hymn as well. The Serbs, however, sing it at a much slower tempo than the Poles do. For those familiar with the Polish national hymn today, it might sound as though Elgar ornamented the melody. Actually, this is the way the melody existed prior to 1918. Immediately following the establishment of the Republic of Poland, the Ministry of Education was given the task of making the melody easier for school children to sing. The passing notes heard in the last phrase of Elgar’s setting of the hymn are noticeably missing in the post-war version. Although competitions were held after the war to search for a new national hymn, “The Dąbrowski Mazurka” became the official hymn on February 26, 1927. A translation of the hymn follows:

Poland has not yet been lost

So long as we still shall live.

That which foreign force has seized

We shall regain by the sword.

March, march Dąbrowski!

From Italy to Poland!

Under your command

Let us rejoin the nation.

The last phrase of the Polish National Anthem “Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła”.

The first example shows how it was sung prior to 1927, while the second example illustrates how it is sung today.

A listening guide for “Polonia” follows. The form of the piece is a free design. The work is scored for full symphonic orchestra and includes the following instrumentation: 2 flutes (2nd doubling on piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, percussion (6 players), 2 harps, organ and strings.

| Section | Measure nos. | Key | Comments |

| Introduction | 1-20 | A minor C minor A minor |

“Allegro molto”: Original martial-like music by Elgar coupled with a two-measure motif based on m. 1 and 6 of “The 1905 Warszawianka”. Motif first appears at measure 4 when played by the bassoons and bass clarinet. |

| A | 21-37 | A minor | “Nobilmente”: A broad, heroic-sounding original melody by Elgar played by the full orchestra. The melody is chromatically altered during the second playing. |

| Transition | 38-44 | modulates | The rhythm of the “Warszawianka” is played by the percussion and violas while winds and remaining strings play a motif from Elgar’s nobilmente. |

| B | 45-92 | E major | “Poco meno mosso”: The melody “Z dymem pożarów” (“Chorale”) is intoned by the English horn, which is later joined by the winds and strings, and finally with full orchestra joining on the last phrase. At a fortissimo dynamic level the lower brass play the penultimate four-measure phrase of the “Chorale” to a descending scale accompaniment by the rest of the orchestra. The music becomes softer and slower until piu lento at m. 85 where the violoncello is given the melody – slightly varied – as a solo. |

| Transition | 93-100 | E minor | “Piu mosso, poco a poco”: “The Warszawianka” motif is now extended into a four-measure phrase. |

| C | 101-140 | E minor | “Allegro molto”: The motif from “Warszawianka” is developed into an entire section using additional melodic material from other measures of the song as well. |

| A1 | 141-150 | E minor | Elgar’s “nobilmente” theme returns. |

| Transition | 151-162 | Modulates to G minor | “Poco piu tranquillo”: Change in mood, dynamics and color. Tremolo strings lead to the modulation, after which the strings are muted. |

| D | 163-210 | G minor | In this section Elgar pays homage to Paderewski and Chopin. It begins with a quotation of the opening theme from Paderewski’s “Fantasia” which in “Polonia” has been transposed a half-step lower from its original key. Played first by the violins, the phrase is echoed by the clarinet. This echo technique is then repeated between the clarinet and flute. At m. 186 the Chopin “Nocturne” is quoted by the solo violin. Expressive flexibility of tempo with markings of “allargando”, “accelerando” and a tempo are heard during Elgar’s use of the Chopin. |

| Transition | 211-229 | Modulates | The “Warszawianka” motif and fragmented versions of the Chopin and Paderewski themes are heard simultaneously until the martial music of the “Warszawianka” completely dominates at m. 221, “Piu mosso, poco a poco”. |

| C1 | 230-295 | E minor | Once more the music of the “Warszawianka” is developed into a section of its own. Prominent is a motif based on m. 17 and 18 of the song where the text “Naprzód, Warszawo!” (Onward, Warsaw!), appears. Dazzling chromatic runs accompany and, following the dramatic luftpause between m. 261 and 262, ascending chromatic scales are played “con fuoco”. |

| B1 | 296-311 | A major | The Chorale returns accompanied by rising arpeggios in the harps and violins which add a sense of urgency in the pleading nature of this tragic song. |

| Transition | 312-329 | Modulates | The “Warszawianka” motif, the first four measures of the Polish national anthem and the first two measures of the penultimate phrase of “Chorale” are heard dovetailing each other, while at other times they are played simultaneously. The entire transition is played “pianissimo”. |

| Finale | 330-379 | F major | “Moderato maestoso”: A change from quadruple to triple meter. The Polish national hymn dominates this section. The anthem is heard twice in its entirety. These complete settings are separated by short development of the mazurka at m. 349 “animando”. The final playing of the anthem at m. 360 “Grandioso” uses all the resources of the orchestra, including full organ, creating a glorious climax to the fantasia on Polish airs. |

| Coda | 380-end | F major | “Allargando al fine”: Based on the dotted rhythm of the first measure of the mazurka. |

Inasmuch as anniversaries present an opportunity to remember and learn from the past, let this 80th anniversary of the 1918 Armistice not only make us recall the horror and tragedy of that Great War, but let it also make us cherish Elgar’s musical response to the plight of a people whose once and future nation was often forgotten and who suffered so horribly in the shadows of the principal players of that terrible world conflict. In October 1999, as the musical world celebrates another anniversary – the sesquicentennial of Frederic Chopin’s death – it will again have the opportunity to reassess another Elgar composition recalling how this English musical giant saluted Poland’s most famous composer by orchestrating the “Funeral March” from his “Sonata in B-flat minor”.

Notes

[1]. Drozdowski, Marian Marek:Ignacy Jan Paderewski – a Political Biography, 1981, p. 68. This article originally appeared in The Elgar Society Journal 11 no. 2 (July 1999): 97-109. Reprinted by permission of the Journal and the author. The Journal’s address is:107 Monkhams Avenue, Woodford Green, Essex IG8 0ER, Great Britain. E-mail: hodgkins@compuserve.com. [Back]

[2]. Davies, Norman: God’s Playground – A History of Poland, Volume II, 1981, p. 378. [Back]

[3]. Watkins, Glenn: Soundings – Music in the Twentieth Century, 1988, p. 464.[Back]

[4]. Drozdowski, Marian Marek: op. cit., pp. 99-103.[Back]

[5]. Jasiński, Roman: “Pamięci Emila Młynarskiego”, Ruch Muzyczny, No. 7, 1960, pp. 4-5. [Back]

[6]. Waldorf, Jerzy: Diabły i Anioły, 1988, p. 101.[Back]

[7]. Jasiński, Roman: Na przełomie epok – Muzyka w Warszawie (1910-1927), 1979, p. 282.[Back]

[8]. Poles also use the Latin word for Poland, Polonia, in reference to its diaspora, i.e., the Polish community living outside of Poland.[Back]

[9]. Panufnik, Andrzej: Composing Myself, 1987, pp. 269-270.[Back]

[10]. McGinty, Brian: Paderewski, 1976, p. 125. [Back]

[11]. Moore, Jerrold Northrop: “Preface to the Full Score of Polonia” in the Elgar Complete Edition, vol. 33, 1992, p. xi.[Back]

[12]. Drozdowski, Marian Marek: op. cit., pp. 73-74. [Back]

[13]. Dulęba, Władysław and Zofia Sokołowska: Paderewski, 1976, p. 125.[Back]

[14]. Moore, Jerrold Northrop: op. cit., p. xii.[Back]

[15]. Panek, Wacław: Polski Śpiewnik Narodowy, 1996, p. 201.[Back]

[16]. Walaux, Marguerite: The National Music of Poland – Its Character and Sources, 1916, p. 13. [Back]

[17]. Wacholc, Maria (ed.): Śpiewnik polski, 1991, p. 57.[Back]

Bibliography

Anderson, Robert: “Paderewski and Elgar’s Polonia.” Musica Iagellonica 1 (1995): 141-146.

Bax, Arnold: Five Fantasies on Polish Christmas Carols; Publisher: Chappell Music Limited, piano/vocal score, 1944.

Britten, Benjamin: Children’s Crusade, op. 82, Publisher: Faber Music Ltd., chorus part, 1969.

Chopin, Frederic: Nocturnes; Publisher: Instytut Fryderyka Chopina & Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne, 1951.

Davies, Norman: God’s Playground – A History of Poland – Volume II -1795 to the Present; Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981.

Drozdowski, Marian Marek: Ignacy Jan Paderewski – A Political Biography; Warsaw: Interpress, 1981.

Dulęba, Władysław and Zofia Sokołowska: Paderewski; Cracow: Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne, 1976.

Elgar, Edward: “Polonia”, op. 76; Publisher: Novello, full score in Vol. 33 of Elgar Complete Edition, 1992.

Elgar, Edward: “Polonia”, op.76; Cond. Sir Adrian Boult. London Philharmonic Orch. EMI, CFP 4527, 1975.

Elgar, Edward: “Polonia”, op. 76; Cond. Sir Andrzej Panufnik. BBC Northern Symphony Orch. BBC Radio Classics, 15656 91942, 1997.

Jasiński, Roman: Na przełomie epok – Muzyka w Warszawie (1910-1927); Warsaw: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1979.

Jasiński, Roman: “Pamięci Emila Młynarskiego”; Ruch Muzyczny, 7 (1960): pp. 4-5.

Kennedy, Michael: Portrait of Elgar; London: Oxford University Press, 1968.

McGinty, Brian: “Paderewski.” Paderewski Day Program, Warren, Michigan: Friends of Polish Art, (1991): 27-33.

Mechanisz, Janusz: Emil Młynarski w setną rocznicę urodzin; Warsaw: Teatr Wielki, 1970.

Młynarski, Emil: Symphony in F major, op. 14, “Polonia”; Publisher: Ed. Bote & G. Bock, full score, 1912.

Mrowiec, Karol (chief ed.): Śpiewnik Kościelny Ks. J. Siedleckiego; Cracow: Instytut Teologiczny Księży Misjonarzy, 39th ed., 1994.

Moore, Jerrold Northrop: “Preface to the Full Score of ‘Polonia'”; London and Sevenoaks: Novello, Elgar Complete Edition, vol. 33, 1992.

Neill, Andrew: “The Great War (1914-1919): Elgar and the Creative Challenge”; Elgar Society Journal, 2.1 (1999): 11-41.

Nowowiejski, Feliks: “Friede, schö nstes Glü ck der Erde, op. 31 no. 5”; Publisher: Akademia Muzyczna im. F. Chopina, Utwory mniejsze na organy, 1994.

Paderewski, Ignacy Jan: Polish Fantasy on Original Themes for Piano and Orchestra, op. 19. Publisher: Ed. Bote & G. Bock, full score, 1895.

Paderewski, Ignacy Jan: Symphony in B minor, op. 24, “Polonia”; Publisher: Huegel & Cie, full score, 1911.

Paja-Stach, Jadwiga: “Polish Themes in Polonia by Edward Elgar.” Musica Iagellonica 1 (1995): 147-158.

Panek, Wacław: Polski Śpiewnik Narodowy; Poznań: Grupa Wydawnicza “Słowo”, 1996.

Panufnik, Andrzej: Composing Myself; London: Methuen London, 1987.

Panufnik, Andrzej: “Polonia”; Publisher: Boosey & Hawkes, full score, 1959.

Popis, Jan: Notes for Paderewski Symphony “Polonia”; (CD recording) Polish Radio Studio S1 Music Label, CD S1-001, Warsaw, 1991.

Reiss, Józef: “W. Statkowski – Melcer-Młynarski-Stojowski”; Łódź: “Wiedza Powszechna” Wydawnictwo Popularno-Naukowe, Muzyka i muzycy polscy, no. 18, 1949.

Stojowski, Sigismond (Zygmunt): Prayer for Poland, op. 40 (Modlitwa za Polskę); Publisher: G. Schirmer, piano/vocal score, 1915.

Vaughan Williams, Ralph: Mass in G minor; Publisher: G. Schirmer, Curwen Edition, choral score, 1922.

Wacholc, Maria (ed.): Śpiewnik polski; Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 1991.

Wagner, Richard: “Polonia”; Publisher: Breitkopf & Härtel, full score, 1908.

Walaux, Marguerite: The National Music of Poland – Its Character and Sources; London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1916.

Waldorf, Jerzy: Diabły i Anioły; Cracow: Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne, 1988.

Watkins, Glenn: Soundings – Music in the Twentieth Century; New York: Schirmer Books, 1988.

Żmigrodzka, Zofia: Notes for “Ferenc Liszt Polonica”; (CD recording) Wifron Music Label, WCD 028, Warsaw, 1994.

Director’s Report

Polish Music And Scholarly Conferences

by Maria Anna Harley

An important part of my duties as Director of the PMRC is to ensure that the subject of Polish music is included in the program of international and national academic conferences. These events are meetings grounds for scholars providing them with opportunities to exchange ideas, start various projects and cooperations, and inform each other about current “hot” issues in their fields. I am very pleased that since coming to USC in the fall of 1996 I was able to organize three such scholarly symposia at our School of Music – one on the music of Henryk Mikolaj Gorecki (in October 1997, as a part of the Gorecki Autumn Festival), one on women composers (in April 1998), and one on Polish Jewish Music (an International Conference held in November 1998). The proceedings of two of these events will provide material for two books that will be published in the Polish Music History Series.But organizing scholarly meetings in Los Angeles is just one aspect of this part of my work. Since 1996, I have proposed several sessions for the programs of scholarly meetings elsewhere; these sessions included my own papers as well as contributions by scholars that I invited to join me for these occasions – in London, England in 1997 (16th Congress of the International Musicological Society, session on contemporary music), in Phoenix, Arizona in 1997 (Annual Meeting of the American Musicological Society, session on Lutoslawski), in Fort Worth, Texas in 1999 (Annual Meeting of the Society for American Music, session on Polish immigrants). The impact of a session at a major academic event is much larger than that of an individual paper – sessions have individual titles and slots clearly marked in the program book. It is hard to miss them. That is why I decided to propose a Special Session on “Polish Identity and Music” for the 1999 Annual Meeting of the American Musicological Society which will be held this November. The proposal was accepted and I will report the session’s progress and impact in the future.

The last category of my contributions to scholarly meetings is giving individual papers, mostly as an invited scholar. The organizers of many of these events know about my work and ask me to speak about a specific topic or about anything I would like to talk. I enjoy these opportunities of preparing presentations based on my earlier research and of branching out in somewhat new directions. Since coming to USC, I have read papers as an invited scholar at conferences in Warsaw (1997, on Lutoslawski’s ideas of death), Heidelberg (1998, on the use of medieval anthem by contemporary composers), Chapel Hill, N.C. (1998, on Gorecki, national identity and ethnic musics), Santa Cruz (1998, on Gorecki’s notions of motherhood), San Diego (1999, on Ptaszynska’s colorful use of percussion). I was also scheduled to appear at two events that I regretfully had to miss: in Cracow (1998, paper on Penderecki’s opera Ubu Rex), Cologne (1998, paper on Ptaszynska’s song cycle, Liquid Light). These papers, sent in as complete packages, with handouts, musical examples, transparencies, were read by others. Most of these conference papers have already been prepared as book chapters or articles for music journals to appear in print this year and in 2000. The revisions take into account interesting new ideas, additions and changes suggested by listeners during the discussion period after each paper was read. Thus, the scholarly meetings provide a “laboratory” for research and stimulate the presence of Polish music topics in music history literature published around the world.

Nonetheless, local events are very important for us in Southern California and I am very pleased to report that a major artistic celebration of Polish culture is being prepared at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art for the year 2002. A major exhibition will feature little-known modernist works from the years 1910-1930 and created in Germany, Poland, Hungary and Czech Republic. There will be numerous Polish exhibits there, and the selection process is now in full swing. Dr. Monika Krol represents LACMA in this undertaking, led by the Exhibition Curator, Dr. Timothy Benson. The preparation stage of this major artistic event included an international symposium, entitled “Exhibiting Central European Modernism” and organized jointly by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Center for Russian and East European Studies at UCLA. So what I was doing at this event? Dr. Monika Krol, who attended our conference on Polish-Jewish music in the fall of 1998, invited me to discuss musical modernism in the context of artistic innovations in Poland. Since I am not an art historian, but a music historian, I decided to investigate the links between experimental artists and musicians, the possible connections and influences of ideas created by the constructivists, formists and suprematists on composers of their, or later time. After a preliminary survey, I realized that the “later” is the key word here: I have found very few examples of interactions of contemporaneous avant-garde, experimental artists and composers.

I entitled my presentation “Parallels and Intersections: Constructing New Forms in Polish Art and Music” and focused on the relationships between modernist music and art. After considering the terminological difficulties (“modernist” or “formalist” mean different things in English, Polish, in music history and in art history), I singled out four options: (a) music created at the same time expressing the same ideals, e.g. futurism, machine-orientation of neoclassical music (parallel); (b) music that artists like and are inspired by (intesection); (c) music that is created according to similar ideals, without conscious imitation or inspiration (parallel) – with reference to emotion, or lack thereof, representation of objects, or lack of it, narrativity, similar formal principles, etc.; (d) music that is created to imitate and express in a different medium ideals taken from the other art (intersection). My talk included many musical examples from works by Aleksander Tansman and Jozef Koffler (contemporaries of the artists) and post-war composers inspired by the earlier avant-garde painters and philosophers of art: Zygmunt Krauze (inspired by the theory of “unism” of Strzeminski, e.g. his Piece for Orchestra no. 1, premiered during Warsaw Autumn Festival in 1970, fragment of the LP cover is reproduced here), Paweł Szymański (interested in Witkacy and Irzykowski’s theories of art), and Hanna Kulenty (interested in formal aspects of construction, as Katarzyna Kobro). The exibition will feature many fringe events, including concerts, and we will have a chance of hearing some of this music that I brought to the attention of the Museum during the exhibition time at LACMA.

The second scholarly conference held in the month of June that I contributed to was the 57th Meeting of the Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences of America, held at Fordham University, New York. I have been a member of this venerable institution since coming to the U.S. (I had been involved in the activities of its Canadian sibling, based in Montreal) but it was my first meeting. I should mention here that it was perfectly well organized by Dr. Thaddeus Gromada and his team and that it was a very enjoyable occasion for all the participants. The PMRC was also represented by Prof. Diane Wilk, our Associate Director, who serves on the Advisory Board of PIASA.

Since the year 1999 marks the 150th anniversary of the death of Fryderyk Chopin I proposed a special session celebrating the music of our greatest composer. I served as the session chair and talked about the reception of Chopin’s music among women composers (Maria Szymanowska, Pauline Viardot, Clara Schuman, Natalia Janotha, Grazyna Bacewicz). Prof. Halina Goldberg (Indiana University, Bloomington) discussed the context for Chopin’s music provided by Warsaw salons – that he attended and performed in before leaving the country. She challenged the prevailing western image of Warsaw as a provincial city, pointing out the variety and number of artistic projects and salon meetings that were held in the capital of Russian occupied part of Poland. The final presenter at the session, Ms. Barbara Milewski (Princeton University) talked about the concept of folk music and its relation to Chopin’s mazurkas. She questioned the myth of a strong direct link between Chopin’s music and that created by the peasants in the country, pointing out instead the connections between Chopin’s artistic creations and their context in little-known art music of Poland of his time (precedents of Szymanowska, Elsner, Kurpinski, etc.). Her thesis will certainly be very controversial, as it challenges the dominant “class-based” beliefs about the sources of national culture.

Anniversaries

Born This Month

- August 4, 1879 – Józef REISS, musicologist, Polish music expert (d. 1956)

- August 7, 1935 – Monika (Izabela) GORCZYCKA, musicologist (d. 1962)

- August 8, 1946 – Mieczysław MAZUREK, composer, teacher, choral conductor

- August 8, 1897 – Stefan ŚLEDZIŃSKI, conductor, musicologist

- August 10, 1914 – Witold MAŁCUŻYŃSKI, pianist, student of Lefeld

- August 11, 1943 – Krzysztof MEYER, composer, musicologist

- August 17, 1907 – Zygmunt MYCIELSKI, composer, writer

- August 18, 1718 – Jacek SZCZUROWSKI, composer, Jesuit, priest (d. after 1773)

- August 20, 1889 – Witold FRIEMAN, composer, pianist

- August 21, 1933 – Zbigniew BUJARSKI, composer

- August 22, 1924 – Andrzej MARKOWSKI, composer and conductor

- August 23, 1925 – Włodzimierz KOTOŃSKI, composer

- August 28, 1951 – Rafał AUGUSTYN, composer, music critic

- August 29, 1891 – Stefan STOIŃSKI, music etnographer, organizer, conductor (d. 1945)

- August 30, 1959 – Janusz STALMIERSKI, composer

Died This Month

- August 15, 1898 – Cezar TROMBINI, singer, director of Warsaw Opera (b. 1835)

- August 15, 1936 – Stanisław NIEWIADOMSKI, composer, music critic

- August 17, 1871 – Karol TAUSIG, pianist and composer, student of Liszt (b. 1841)

- August 21 1925 – Karol NAMYSŁOWSKI, folk musician, founder of folk ensemble

- August 22, 1966 – Apolinary SZELUTO, composer and pianist, member of Young Poland group (b. 1884).

- August 23, 1942 – Wacław WODICZKO, conductor (b. 1858), grandfather of Bohdan, conductor

- August 27, 1865 – Józef NOWAKOWSKI, pianist, composer, student of Elsner, friend of Chopin

- August 29, 1886 – Emil ŚMIETAŃSKI, pianist, composer (b. 1845)